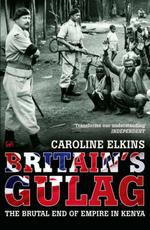

Britain's Gulag - The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya

Caroline Elkins

475 pages including index

published in 2005

Before Tom Wolfe used "Mau Mauing" to describe the ways in which well meaning, white government officials where cheated out of welfare money through racial intimidation, Mau Mau was synonymous with a much greater terror. Mau Mau was the stuff of white colonialist nightmares: a freakish native cult of criminals and gangsters that savagely attacked innocent white settlers in their very homes, killing them and their families, mutilating their bodies. Sure, these people said they were freedom fighters, but you couldn't take this claim seriously. Everybody who mattered knew Kenya wasn't ripe at all for independence, that only the poison the Mau Mau spread through their pagan rites would cause the natives to question the benevolence of the British civilising mission in the country. Britain was therefore justified to use harsh measures to suppress this savagery and fortunately managed to do so, protecting the white settlers and loyal natives and crush the rebels, though it took them eight years, from 1952 to 1960 to do so.

That's the myth of Mau Mau. The reality as Caroline Ekins describes in Britain's Gulag - The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya is far different. There were incidents of Mau Mau savagery, but the British and settler response to it was much greater and was systematic, not incidental. It was under the Kikuyu of central Kenya, the most populous of the ethnic groups in Kenya and the group with the greatest grievances against British rule, as much of their land had been appropriated for white settlers that the Mau Mau rebellion was the most widespread, therefore the British did to the Kikuyu roughly what the Germans did to the Polish during World War II. The nazi plan for Poland had been to destroy its population as a people by murdering its intellectual elite, remove it from all the best parts of the country and herd the rest into the wastelands to serve as uneducated slave labour, with any resistance brutally put down. What the British did to the Kikuyu in Kenya was not quite as bad, but it came awfully close. It was motivated by security concerns rather than deliberate planning, but the endresult was still that less than fifteen years after World War II the British in Kenya had recreated much of the nazi system in dealing with the Kikuyu's struggle for freedom.

When the rebellion begun in earnest in 1952, the UK was still committed to keeping as much of its colonial empire as possible. Sure, it had to evacuate many of its Middle East protectorates due to money trouble and had to give up India, but that didn't mean it was now resigned to decolonialisation, especially not of Kenya. With India gone, Kenya was the jewel in the crown of the remaining British empire, its most succesful and profitable colony, wit a large population of white settlers, who enjoyed a luxurious and even debauched lifestyle largely at the expense of the native population, of which the Kikuyu were the greatest victims, as it had been mostly their land which had been taken away. To control the Kikuyu and other natives, the British had created a loyalist elite of native chiefs and their hangers on, who e.g. had the right to force their subjects to work unpaid on their farms.

The colonial government's response to the emergence of a freedom movement, was at first to target those who it saw as its leaders, including Jomo Kenyatta, the largely conservatice future prime minister of Kenya. He was convicted in a sham trial of "managing and being a member of Mau Mau society" and sent off into exile, where he was quickly joined by hundreds if not thousands of other suspected Mau Mau leaders. This, it was assumed, would break the back of the rebellion. At the same time settler "defence forces" and various British and colonial amry and police units were engaged into a counterinsurgency campaign in central Kenya, attempting to smoke out and destroy the Mau Mau, terrorising Kikuyu villages and mass detaining suspected rebels. Elkins provides several examples of such raids and it doesn't make for easy reading, especially not the example of the woman whose husband had already been shot dead, being kicked and punched by a group of soldiers outside her house, with her terryfied two year old son trying to hide behind her; the last she saw of him when she was lead away was him lying dead on the ground...

But even this level of brutality did not end the rebellion, as more and more Kikuyu seemed to have become "infected" with the Mau Mau "virus". In response, an "immunitisation" and "rehabilitation" programme slowly evolved. In Nairobi, all Kikuyu were arrested, screened and most either deported to the Kikuyu Reserves, or kept in concentration camps, awaiting further screening. Squatters outsides the reserves were also arrested or deported, with the result that some 77,000 or so Kikuyu were interned in concentration camps by 1954. This were mostly men, though there were thousands of women and children imprisoned as well.

The camps gradually morphed from a temporary storage solution into a complete system for re-educating and rehabilitating the Kikuyu, where loyalist and settler screeners determined who was Mau Mau hardcore, who was Mau Mau but salvagable and who was not Mau Mau but needed education. Though there was some idea of creating a proper hearts and minds campaign, in practise this was mostly a case of torturing and brainwashing people into denouncing their Mau Mau oaths. New arrivals were stripped of their clothing and forced to run through a delousing bath, in which quite a few drowned or were drowned, then screened where they were routinely tortured, varying from waterboarding to mutilation, with a particular focus on castration, followed by months and years of forced labour and more torture and screenings. At the end, when rehabilitated most would return to the Reserves, though the hardcore would be exiled to permanent labour camps in the worst parts of Kenya.

Meanwhile in the Reserves themselves, the entire population was forcibly moved away from their homes to be concentrated into some 800 new tightly controlled prison villages, which were ruled over by loyalists and settlers. The population of these villages was at first largely female, as so many men where still imprisoned in the Pipeline, as the concentration camps were collectively called. the villages served as central labour depots, with the population forced to work on the loyalist and settler estates surrounding it. Food was deliberately scarce, as people could only work on their own lands once a week or so, if lucky. Because so many people were concentrated in too small areas, disease was rife as well. Finally and worse, the largely female population suffered under loyalist and settler brutality, torture, murder and of course rape.So there you have it, a system that rivals that which the Germans put up in Poland, with a population bereft of its leaders, used as slave labour and subject to every kind of assault its oppressors could think of. And this less than fifteen years afrter World War II. And in the end it didn't work, as Kenya became independent three years after the colonial government announced it had won the fight against Mau Mau and ended the Emergency. Independence came because despite the repression the Kenyans continued to fight for it, while in the UK itself a large grassroots movement attacking the barbarism needed to substain British rule in Kenya had emerged, led by Labour Members of Parliament like Barbara Castle.

But in a real sense, the repression did achieve its goals. When independence came, the British settlers kept their land and priviledged positions in Kenya, while those who returned to Britain got ample compensation. The Kikuyu independence movement, which had struggle for land as much as freedom was left with empty hands, as a new post-colonial elite took over from the British, including many of the loyalists who had inflicted such suffering on the Kikuyu only years before. In the end, few people weere held to accoutn for what they did, had to pay for their crimes during the Emergency and the departing bureaucracy made sure few people could ever be convicted for them, as they destroyed almost all evidence of these crimes and left the archives almost empty.

Many of the stories recounted in Britain's Gulag - The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya therefore are based on oral testimony recorded by Elkins herself in Kenya, after she became aware of how much of a gap there was between the official reality recorded in the governmental archives in Kenya and England, and the truth. As she mentions in her preface, Elkins didn't set out in her research to prove this truth, as she herself had bought into the myth of the succes of Britain's civilising mission in Kenya. It's therefore all the more commendable that when she became suspicous of this myth she went and set out to prove her suspicions. She could've just adhered to the official version of the truth, but didn't.

Britain's Gulag - The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya is no easy read, even for this sort of subject, as Elkins includes some graphic but necessary accounts of torture and rape. It took me much longer to read than normal because of this, but in the end I'm glad I did, because it shows how little right we have in the west to pride ourselves on our level of civilisation. Kenya is a strong rebuttal of the idea that the west has a right to interfere in Iraq or Afghanistan or Kosovo or elsewhere because we're defending civilised values by doing so.

Read more about:

Caroline Elkins,

Britain's Gulag,

Kenya,

history,

book review