A Cure for Cancer

Michael Moorcock

261 pages

published in 1971

Michael Moorcock is interesting. He started out as a hack, writing purely for money for the UK pulps but quickly grew dissatisfied with that and the state of British science fiction as a whole. He then of course helped start up the New Wave, together with his older coutnerparts Brian Aldiss and J. G. Ballard. He got his start and first breakthrough writing fantasy, then helped to force science fiction to grow up somewhat and he finally ended up breaking out of the science fiction "ghetto" entirely, writing literary fiction and could now be considered, like Ballard, part of the UK's literary establishment.

Yet unlike Ballard, he has never stopped writing science fiction and fantasy and has never denounced his past or been ashamed of it. He always has written whatever he wants to write, he has just gotten better at it and somewhat more mature.

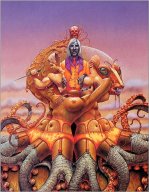

A Cure for Cancer is part of that maturisation process and is most interesting if you look at it that way. As a novel, it's very much of its time and looks dated. The acknowledgements page carries a warning that "this novel has an unconventional structure", but all that is unconventional about it is that cuttings from various unlikely sources, seemingly unrelated to the text, have been used as chapter headings. It is both flashy yet curiously sedate and not as half as shocking as it thinks it is.the book itself is the second novel in the Jerry Cornelius quartet, the first being The Final Programme. I had read all four novels in this series a long time ago, during a particularly rainy family holiday when I was sixteen, but in translation. The protagonist of the series, Jerry Cornelius is Moorcock's version of the superhero everyman, part Steed of the Avengers, part angry young rebel, part decadent "artiste". His adventures are usually quite surreal and not bound by the usual rules of storytelling. If you exect a coherent plot here, you will be disappointed; A Cure for Cancer is more of a travelogue, a series of vignettes loosely bound into a novel.

More interesting than the plot is the theme of the novel. It is a deeply cynical novel, mistrusting even the motives of its "hero", who is more led by events than actively taking part in the plot at any rate. Moorcock grew up during World War II, in a London ruined by German bombardement, the ruins of which were still present long after the war had ended. Though he did take to the counterculture that sprung up in the sixties (writing songs for hawkwind e.g.), he always remained somewhat cynical, far more so than his American counterparts. (In fact, I think this was a common reaction in the UK, where the whole youth culture of the sixties to me always seemed far more decadent and cynical than the hippydrippy Haigh-Asbury cliches of San Francisco.)

It's this decadence and cynicsm in which A Cure for Cancer is drenched. The traditional authority figures (church and state) are either absent or buffoons, but the alternative, in the form of Cornelius isn't better. The message seems to be that everything is going downhill, entropy is gaining and nothing can be done about. Everything that is solid melts into air, as it where. The old securities are gone, the new alternatives offer no selter. The best example of this is the destruction envisited on Derry and Toms, one of London's great prewar warehouses, in the first chapter.

It is an ambitious undertaking and unfortunately at this point Moorcock was not a good enough writer to tackle it in depth. A Cure for Cancer lacks coherence and depth and is dated in its attitude in a way Moorcock's later books wouldn't be. At best this is an interesting failure.