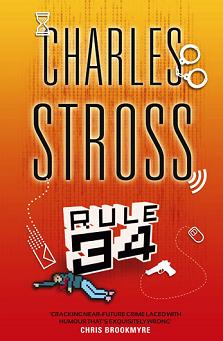

Rule 34

Charlie Stross

358 pages

published in 2011

It's only thanks to Christopher Priest's tirade about this year's Clarke Award shortlist that you remember that you haven't reviewed Charlie Stross latest novel, Rule 34 yet. You know that, like Halting State, which it is a sequel to, it's written in the second person and you briefly toy with the idea to write your review the same way. But then you come to your senses and decide to write the rest of the review in a less irritating way.

Not that I minded the second person point of view in Rule 34, as Charlie Stross made it work and it fit the central metaphor of these books, reality as a massive multiplayer immersive game. At the same time I can see where Christopher Priest is coming from when he writes:

Stross writes like an internet puppy: energetically, egotistically, sometimes amusingly, sometimes affectingly, but always irritatingly, and goes on being energetic and egotistical and amusing for far too long. You wait nervously for the unattractive exhaustion which will lead to a piss-soaked carpet.

It's funny because it's true, if mean spirited. As a writer Charlie Stross does bring a kind of geeky enthusiasm to his novels that can be wearing if you don't share his interests. Stross' writing style is snarky rather than witty, more interested in conveying information than in a mellifluous turn of phrase and he can be prone to a bit of infodumping. As with using second person point of view, it is not to everybody's tastes. And if that's the case for you, as it seems to have been for Priest, it would be a slog to get through Rule 34.

Yet neither his writing style nor his choice of the second person viewpoint is a flaw in Rule 34; instead they're deliberate choices made to enable Charlie Stross to tell the story he wanted to tell with this novel. Like its predecessor Halting State this novel is an attempt to create a plausible near future Scotland by looking at various contemporary trends and extrapolating them a couple of decades into the future. As fitting an "internet puppy", most of these changes are technological, extensions of current computing trends a few years down the road, but Stross looks beyond what might technologically be possible and embeds these developments in a political and sociological context.

The central idea at the heart of Rule 34 is that of the panopticon singulary, the way in which technological developments, commercial pressures and the law come together to kill privacy. The second person viewpoint in which it is written drives this home, because it makes the reader complicit in the panopticon: the characters become the reader's avatars, as if this is a videogame rather than a novel. At the same time, Stross' writing style, detached & snarky distances you from the characters as well which again reinforces that sense of complicity, of voyeurism.

For the people caught in Rule 34's plot, Detective Inspector Liz Kavanaugh, banished to the Rule 34 Squad, the one dealing with all the pervy crimes, Anwar Hussein, a Scottish-Pakistani petty criminal turned honorary consul for a small, new Central-Asian state and "John Christie", point man for The Organisation, having to negotiate their way through life with this sort of omnipresent surveillance is just part of their daily routines. So Liz spents her entire working life in CopSpace, through which she both has access to all data the Scottish police forces acquire and the system can keep taps on her. Hussein meanwhile is expected to keep his smartphone on and with him everyday so the polis can snitch on his location 24/7, while "Christie" has to take pains to avoid areas with too high a surveillance level, like airports.

Rule 34's story starts with Liz being called out to a crime scene, a suspicious death of an ex-criminal, who died while getting a colonic irrigation from an old Soviet machine that used to belong to Ceasescu... A true double wetsuit job, it at first just seems a regretable accident, but of course there's more going on. Anwar Hussein meanwhile is beginning to wonder why exactly he has been made honorary consul for Issyk-Kulistan for. "John Christie" finally knows exactly what he's in Edinburgh for, to recreate the Scottish branch of The Organisation. Each of these three protagonists thinks they're at least somewhat in control of their own lifes, even if they're now clearly been caught up into something bigger, but this turns out not to be the case.

Instead through the course of the novel it becomes clear that they are each being nudged in some way or another to perform certain actions, by somebody who knows how to do this for each of them individually and without their knowledge. Nudge theory is quite popular with the current British government, who see this as a cheap and easy way to get the hoi polloi to behave themselves and the more data you got on people the easier it becomes to find the right nudge. Current implementations are still primitive, in Rule 34 Stross imagines what it would be like if the people doing the nudging had perfect methods and all the data needed to use them, thanks to the panopticon. None of the protagonists ever quite catch up with the fact that they were being nudged or the overarching plot these nudges served, but the reader does get to know who is behind everything that happened and why.

As said Rule 34 sets out to create a plausible near future world which we could concievably get through from where we are now. Charlie Stross has done the most difficult job any sf writer can undertake, try and predict not just what new technology could do, but how it will be used and how the law, government and societies as a whole will handle it. As such then it is a worthy novel to be on the Clarke Awards shortlist.

Webpage created 06-09-2011, last updated 01-04-2012.