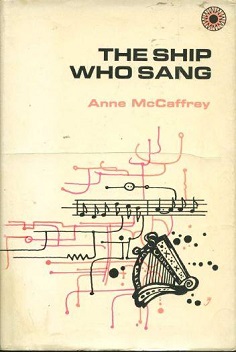

The Ship Who Sang

Anne McCaffrey

205 pages

published in 1969

Some writers you can only appreciate if you discover them in the golden age of science fiction -- twelve -- because at that age you're less likely to notice the two dimensional characters, slipshod plotting or obnoxious politics you would've noticed as a more experienced reader. McCaffrey is such a writer for me. I loved her books when I was twelve and reading them from the local library, but trying my hand at some of her later works ended in disappointment. There's also the danger of rereading cherished childhood classics and finding that in hindsight, they're not so great after all. With McCaffrey's early Dragonriders novels I already took that gamble and got lucky, now I've reread perhaps her best known novel outside that series and see if The Ship Who Sang was as much of a tearjerker as I remembered.

Sentiment is an underrated emotion in science fiction, something we're a bit embarrassed about, but which plays a greater role than you'd expect in such a "rational" genre. Quite a few classics thrive on it -- "Helen O'Loy", "Green Hills of Earth", "Faithful to Thee, Terra, in Our Fashion" all spring to mind -- and as I remembered The Ship Who Sang, it positively wallowed in it, in this story of a severely disabled girl whose only hope for any sort of life was to become the "brain" of a spaceship, who then found love in the arms of her "brawn" partner only to lose him to cruel, cruel fate. The perfect sort of story for a sensitive twelve year old, but would it hold its appeal?

Sadly, no

The problems start literally from the first paragraph:

She was born a thing and as such would be condemned if she failed to pass the encephalograph test required of all newborn babies. There was always the possibility that though the limbs were twisted, the mind was not, that though the ears would hear only dimly, the eyes see vaguely, the mind behind them was receptive and alert.

The electro-encephalogram was entirely favorable, unexpectedly so, and the news was brought to the waiting, grieving parents. There was the final, harsh decision: to give their child euthanasia or permit it to become an encapsulated 'brain', a guiding mechanism in any one of a number of curious professions. As such, their offspring would suffer no pain, live a comfortable existence in a metal shell for several centuries, performing unusual service to Central Worlds.

That's a fairly dodgy attitude even in a novel written at a time and in a country that had no problems with involuntary sterilisation of undesirable people and nonconsentual medical experiments, let alone now we've sort of managed to accept disabled people as human. To have a writer approvingly talk about euthanasia for mentally disabled babies, or lifelong servitude for those merely severely physically disabled, if their parents allow it, is a reminder of how social darwinist (or downright fascist) science fiction could be and sometimes still is.

It left a nasty taste in my mouth, though for the rest of the novel this background is never referred to again and Helva, the protagonist, is perfectly happy being a Brain. What reinforces that feeling is the way the Brains are forced into servitude to pay off the huge debts they occurred from being kept alive the way they are, which they have to work off in service to Central Worlds. What's more, anything that Helva needs as a ship to fulfil the missions she's sent on she needs to pay for herself, including any damage done to her in the mission. It does feel a lot like slavery, even if she does get paid for these missions as well. All of this is completely ignored in the stories that make up this novel, just part of the background, a device to get Helva to go on dangerous missions to pay off her debts.

I didn't remember any of this from the last time I read The Ship Who Sang, decades ago; what I remembered was the romantic story at the heart of it, as Helva comes of age and gets her first partner, the "brawn" who will handle all those physical tasks on planet she can't do herself. It's during the party for the eight candidates that Helva gets her name as "the ship who sings", as she reveals her ability to do just that and turns out to have a perfect voice that can do anything the best "normal" singers can do. That's when she first meets Jennan, the only one to consistently talk to where her physical presence was located in the heart of her ship-shell, the one she immediately falls in love with and who actually dies less than ten pages later. The rest of the novel is about Helva dealing with her loss and grief, ultimately finding new love in the strangest of places.

Because this is a fixup novel however, with each story in it originally having been published as a standalone, the characterisation of Helva is rather two dimensional and that deep love and deeper grief doesn't look so impressive anymore as it did at age twelve. The sentiment is there, but much of it has dissipated after the first two stories, McCaffrey preferring to tell perfectly good sf puzzle adventure stories for the rest of the book. These are decent enough on their own, but I missed the emotion in them I remembered.

In its place was something more nasty, a deep ingrained sexism that again I completely missed the first time around. Helva is consistently shown to be "not like other girls", one of the boys, while other women are either victims or harpies, largely illogical and emotional, with things like logic and emotions explicitly shown in gendered terms. It's all very Heinleinian, with McCaffrey having the same sort of this is how the world works and anybody who thinks otherwise is a fool tone in her writing her. It's very offputting and offensive once you notice it.

Without the sexism, without the dodgy background McCaffrey gave the novel, what remains is a great idea executed through decent if not worldbeating stories. It's typical of the science fiction of this generation that most of the interesting stuff is discarded so quickly, largely due to the length restrictions it had to labour under. This after all is a novel of barely 200 pages, which tells half a dozen of stories during it. That leaves little room for anything but plotting.

A bit of a disappointment then, another book I'd with hindsight should've left to memory.

Webpage created 04-05-2014, last updated 13-05-2014.