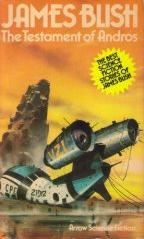

The Testament of Andros

James Blish

216 pages

published in 1973

James Blish was a science fiction writer of the same generation as Isaac Asimov, the first science fiction writers to have grown up with science fiction as a separate genre, to have become science fiction fans before they became science fiction writers. Blish's first short stories were written in the early forties, before World War II interfered, so it was only in the fifties that he made his reputation. During that decade he wrote quite a few classic short stories and novels, including the Cities in Flight series, with its vision of New York flying off amongst the stars and A Case of Conscience, in which a young Jesuit wrestles with the question whether or not the aliens he lives amongst posses souls. At the same time, writing under the pseudonym of William Atheling, Jr., he was one of the pioneers in applying literary criticism to science fiction. His later work is less interesting, being spend mostly on writing Star Trek novels.

Though Blish is an important early science fiction writer, one who has written several excellent novels and short stories, I've always found myself a bit lukewarm about him. I've read the novels I've mentioned above, attempted some other, later works of his, as well as most of his better known short stories; they were alright, but no more than that. Part of the trouble I had with him is that he, for a science fiction writer, had quite a conservative pessimistic atttitute towards the future, adhering to a Spenglerian, cyclical view of history, most notably in the Cities in Flight series. I got nothing against a bit of conservatism or pesssimism in my science fiction perse, even if I don't share it, but Blish's philosophy is a particularly dreary one.

Luckily his short stories largely escape this dreariness, so when I discovered that The Testament of Andros was not as I thought one of his later novels, but instead a collection of his best stories, as chosen by Blish himself, I took it out to read. (Such misunderstandings happen when you leave books sitting on your shelves for half a decade before looking at them.) Some of the conservatism is still on display however in the little introductions Blish gives to his stories, in one of which he refers to his love for real music, not that "bad dance music" that bands like the Beatles play these days.

The Testament of Andros was first published in 1965, as The Best of James Blish. For the revised edition Blish dropped one story, There Shall Be No Darkness for two later stories, How Beautiful with Banners and We All Die Naked. I'm not sure this was an improvement. Nevertheless, there are several classic stories included in this collection, even if most stories here are good but not excellent.

-

Surface Tension (1952)

Originally published in a much different form as Sunken Universe. Blish calls this is his most popular story and is puzzled as to why this is. Personally I think it's obvious why this struck such a cord with readers, as it encapsules one of science fiction's most cherised myths: that of the indominatable spirit of humanity that will lead it to dominated whatever environment it finds itself in. In this case, it's a large puddle of water on an alien planet, seeded with microscopic humans. Well concieved, well told and with a good eye for believable scientific detail that showcases the alien world Blish has created. -

Testament of Andros (1953)

Six different views of the end of the world, or are they six different attempts by the same person to come to grips with his own mind? -

Common Time (1953)

The best story in this collection after Surface Tension. There had been two attempts at manned faster than lightspeed ships before, both of which returned froom their maiden flights without their pilots. Now the third ship has launched and Garrad experiences for himself what has happened to the first two pilots. A good, difficult but fair science fiction puzzle story. -

A Work of Art (1956)

Sometime in the future, Richard Strauss is resurrected to create his final masterpiece. But which is the real work of art? -

Tomb Tapper (1956)

A Cold War story, in which a member of the Civil Air Patrol finds what he thinks is a downed Soviet rocket fighter and uses his "tomb tapper" to read the last thoughts of the dying pilot, only to find them to be so strange that they have to come from some alien being. -

The Oath (1960)

After the nuclear holocaust, one self-taught doctor has rejected the hippocratic oath. -

How Beautiful with Banners (1966)

An unfortunate encounter with an indigenous lifeform on Titan leaves dr. Ulla Hillstöm dead, but not before she has given an important though doublesided gift to the aliens. The Titan here is nothing like the real Titan, of course. -

We All Die Naked (1969)

Almost a Blishian attempt at writing a new wave science fiction story, it's set in a future in which pollution not to mention garbage is way out of hand. Not very good nor memorable.

Read more about:

James Blish,

The Testament of Andros,

science fiction,

book review