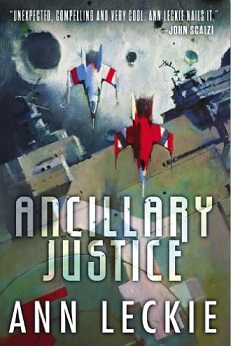

Ancillary Justice

Ann Leckie

385 pages

published in 2013

It’s funny how you don’t notice how ingrained gender is until you get your nose rubbed in it. In Ancillary Justice, Ann Leckie makes it clear by the third page that when her protagonist Breq uses “she” and “her” she uses it as a neutral pronoun, yet unless I paid close attention or Leckie explicitly outed a character as male, I kept thinking of every character she meets as female. That’s I think a response more readers will have, as we’re just not used to thinking of the female form as universal; traditonally it has always been “he” or “him”, or something like singular “they” for those of us aware that the male isn’t actually universal. It may seem like a too clever writing trick, a clumpsy attempt at showing the reader the gender assumptions build into the very language we use, but I don’t think this is actually what Leckie had in mind. What it does instead is establishing the fundamental strangeness of Breq herself even before we learn she’s the last remaining component of a thousands years old warship’s AI.

That consistent use of “she” and “her” foregrounds the difference of the Radchaai culture Breq comes from. It’s a bit of unexplained strangeness that tells a lot about their society, culture and history, most importantly that the Radchaai are inherently matriarchal in the same way most if not all actually existing human societies are patriarchal. But there’s more going on with Breq’s gender blindness, as other Radchaai seem to have far less trouble differiating between men and women, even if they use the same pronouns for both. Meanwhile Breq not only has pronoun troubles, she also has trouble remembering which secondary sexual characteristics are male and which are female. It’s this that singles her out as not quite human.

As it turns out, Breq is only the last remaining fragment of One Esk, which used to convince of some twenty ancillaries, these being the depersonalised bodies of Radchaai enemies converted to housing an AI submind. One Esk herself was just one part of the warship Justice of Toren, which has thousands of ancillaries — though most are deep frozen until needed — alongside its Radchaai crew. Breq’s memory, as One Esk, goes back thousands of years, most of which was spent conquering and “civilising” various non-Radchaai systems.

The Radchaai, it seems, are not very nice, an expansive interstellar empire busy assimiliating every other human system and have done so seemingly forever. In an offhand mention halfway through Ancillary Justice it’s explained that all this is done to protect the mother system, a giant Dyson Sphere at the heart of the Radchaai Empire, whose inhabitants are barely aware of the outside universe. It’s an interesting idea for a galactic empire, reminiscent of the popular imagination of what the Roman Empire was like. The Radchaai method of operation is to attack and conquer other human systems, subvert or kill its rulers, crush resistance, then offer the remaining, docile population membership in the empire.

Ancillaries like One Esk/Breq play a large role in this subjugation/pacification, unhesitantly obeying orders of their (human) officiers but without all the messy rape and abuse of human soldiers. To non-Radchaai meanwhile they’re objects of fear and loathing, being after all the converted bodies of previous victims of Radchaai expansion.

When we first meet Breq she’s on a quest of vengeance against those in the Radchaai empire who killed her, killed One Esq, having been a singleton for nineteen years when the story opens. In Ancillary Justice‘s second storyline we learn how this murder came to pass, as the story goes nineteen years back in time, to One Esq’s last posting in a backwater city on a newly pacified world. In essence then, this is a colonial murder/revenge story.

The colonial revenge story is one that’s somewhat old fashioned these days, now that western countries don’t really don’t have colonies anymore, just some protectorates and overseas departments it doesn’t do too much good to look too closely at. But they used to be a thing in the twentieth century, stories about murders that the colonial justice system couldn’t handle because they were perpetrated by those at the heart of it, to those who were the least protected by it, leaving no other option than to go outside it to get justice. It’s of course impossible to have true justice in a colonial situation, as colonism depends on declaring some peoples second class, non-citizes, slaves or sub alterns. One Esk is the latter, a willing tool of the oppressor because she literally cannot be anything but. What shook her so hard that her programming failed is what at the heart of Ancillary Justice‘s plot.

As a whole though, it’s so much more than that. Leckie is a brilliantly evokative writer and Ancillary Justice was one of those novels I couldn’t wait to finish yet didn’t want to end. She has a great eye for the telling detail; for example I loved the way she had One Esk sing to herself. If you have twenty bodies to sing with, why wouldn’t you? Yet she’s the only such ancillary to do so…

I’d only heard of Ancillary Justice or Ann Leckie when I read Ian Sales’ review. At the time she was new enough not to have a Wikipedia page. In his review he mentioned that Leckie had a lot of buzz behind her, similar to Kameron Hurley with her first book, but I was skeptical. If it was so good, why hadn’t I heard of it before? However, Sales’ review was enthusiastic enough to get me to try it for myself and now I know why Leckie deserved the buzz. She’s nominated for a Clarke Award; I hope she gets it.

No Comments