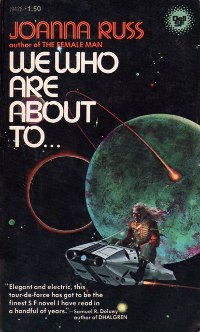

We Who Are About To…

Joanna Russ

170 pages

published in 1975

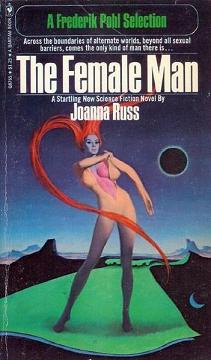

We Who Are About To… is arguably Joanna Russ’ most famous and controversial novel after The Female Man. That novel became famous because of its outspoken feminism, still rare in science fiction at the time; if we’re honest, still somewhat rare today. We Who Are About To… comitted a greater sin however, by attacking the optimistic, can do attitude of classic science fiction, the belief that any adversity can be overcome by man’s unique fighting spirit. It’s not just that the protagonist doesn’t win in the end; even Asimov the arch-optimist had written “Founding Father” ten years earlier, a story in which four astronauts fight but fail to terraform a planet before it kills them. No, the real problem is that she rejects the choice out of hand and choses not to fight, not even to try.

That of course went against the grain, with plenty of science fiction fans being outraged about it, if I can believe the contemporary fan publications. But We Who Are About To… is about more than just rejecting science fiction’s traditional morality, it’s also a novel about how die. Slightly over half way through the story the central conflict of whether or not to fight has already been resolved, in favour of not to. The rest of the story is all about how you die. This part of the book has received less attention than the first half.

The plot is simple. A small, mixed group of interstellar travellers crashland on an unexplored planet barely liveable, far away from civilisation. Their hopes of being picked up are almost nil. They have shelter in form of the lifeboat that has set them down and enough supplies, water and tools for several months. They’ve no idea if there’s life on the planet and whether or not they can eat it, or it can eat them. The outlook is bleak, but they are all determined to make a go for it. All, but one, our protagonist, who is the only one to realise that rebuilding civilisation is not on the cards and wants nothing to do with it.

She argues as such, but is overruled. Civilisation is going to be restored, which means the women will need to start populating the world and make babies. Our hero obviously doesn’t agree with this and fight backs, eventually escaping the camp and moving away somewhere where she can die in peace. In the end she ends up killing everybody when they won’t leave her alone, then dies herself.

Russ does load the dice a bit. The narrator herself is an elderly, slightly embittered, cynical, “difficult” no-nonsense woman, not dissimilar to some of Russ’ heroines from The Female Man. We see events only from her point of view and she has little sympathy for any of her fellow passengers, who all come across as nasty stereotypes one way or another. The succesfull business man and woman and their bratty daughter, the strong but dim ex-football player, the smug, status aware but intellectually stagnant professor, the blonde floozy, the bitter young woman who hates everybody. Almost from the start they are all hostile against her, the men all determined to play pioneer, the women, apart from her, content to go along with this. The others are more than happy to force the narrator into going along with their agenda, tying her to a tree and raping her if need be. It’s not subtly done, which somewhat lessens the impact, but sometimes you need a sledgehammer to crack a walnut.

Once the narrator has escaped and killed her shipmates, not without some regrets, the story’s focus switches to how she deals with dying. She doesn’t commit suicide, just moves away from the lifeboat back to the cave where she hid before and stops eating. It takes time for her to die this way and she has long days to think about her life and to deal with any regrets she had about it, or about what she did to the other survivors. She hallucinates, but is never unaware that these are hallucinations, she gets weaker, slips away more and more and finally dies quietly: “well it’s time”.

This was the same way my wife died when she stopped treatment last year, well, without all the killing of course and how Russ described it was both familiar and emotional for me. She got the process right, the way in which it seems to drag out, then goes much more quickly than you expected, then suddenly the end is there. For me this was far more confrontational, far more powerful than the first half of the story.

I’m not sure in the end whether We Who Are About To… is actually a good novel, rather than a strident one. It was certainly a necessary one, a much needed kick in the pants to science fiction’s innate sense of human superiority.