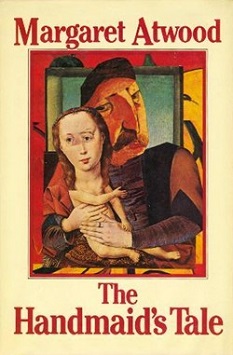

The Handmaid’s Tale

Margaret Atwood

308 pages

published in 1985

About a decade ago, when promoting her book Oryx and Crake, Margaret Atwood said some dumb things while distancing it and herself from science fiction, insising it was “speculative fiction” (ironically a term invented by that most hardcore of sf writers, Robert Heinlein when he tried to make sf respectable half a century before Atwood) and being dismissive about “talking squid in space”. Science fiction fandom has a long history for (imagined) sleights and while Atwood has long since walked back her remarks, sf fans tend to still be a bit grumpy about it. Yet Atwood does have a point that she isn’t writing for science fiction readers and therefore her books shouldn’t be judged by science fiction standards.

Which is fair enough. If you read the Handmaid’s Tale it soon becomes clear that though it is science fiction, it’s science fiction in the dystopian tradition of Orwell and Huxley rather than in the tradition of e.g. Heinlein’s If This Goes On…, another story of religious oppression in a future America. That has flying cars and blaster guns and other sfnal paraphernalia though no space squid, while Atwood’s story is set in what are still recognisable eighties suburbs.

You get the impression that Atwood wanted to keep her setting as mundane as possible to enable her readers to take it seriously in a way they wouldn’t have been able with the Heinlein, because all that sf furniture would be in the way. Not that Atwood doesn’t sneak in some, actually quite a lot, of sfnal prediction, in her backstory of how the America of The Handmaid’s Tale came to be, but most of that is political and sociological rather than technological.

Dystopian fiction, even more so than science fiction in general, always shows the age it was written in, the specific dangers it warns against quickly becoming obsolete. This is true of the Handmaid’s Tale as well, rooted as it is in second wave feminism, the Iranian revolution against the Shah and the rise of the fundamentalist right in America in the early eighties. Atwood basically predicts a new moral crusade in America in which anti-porn feminists and christian fundamentalists join forces, after which a fundamentalist coup turns the US into a explicitly Christian dictatorship similar to real life Iran. Some of that backstory might seem quaint now, but the America Atwood created is still chilling, if only because there are still people out there whom would consider it an utopia.

Dystopias are supposed to be universal and timeless; “a boot stamping on a human face — forever” as Orwell put it. Every dystopia shares that same flaw, like their utopian counterparts of being outside history, in stasis. But The Handmaid’s Tale isn’t. It’s epilogue made clear that the Dominion of the US came to an end, that was part of a broader late 20th century trend towards gender repressive theocracies, along with countries e.g. Iran, quite possibly also an inspiration for Atwood in real life. That makes The Handmaid’s Tale so much more chilling than the perfect dystopia of 1984, because all the suffering shown in it is reduced to a presentation during an academic conference, of no great concern to the historians talking about it.

That callousness is much more frightening to me than imagining a future in which everybody is either victim or oppressor. It’s also shown in the main story, when the protagonist, Offred, encounters some Japanese tourists on a visit to Gilead, men and women both, to whom she’s no more than a curiosity, her clothing and status something exotic to tell the folks back home about. Their indifference, as that of the historians in the epilogue, more interested in who Offred may have been an handmaid to, is jarring when you spent the rest of the novel in Offred’s head. The epilogue shows she at least did get her story out in the end, even if few people cared.

I grew up in a fairly leftwing family, of a rather middleclass sort and that meant that my parents had a lot of magazines and books about various oppressive regimes around the house which I, as a verocious reader, read quite a lot of. Not to mention the books about domestic abuse and child abuse my father also brough home for his work, as a council civil servant working on these issues. The Handmaid’s Tale, the story of Offred, brought down so low we never learn her real name, only that she’s Of Fred, reminds me a lot of some of those stories told about e.g. women in Chile or South Africa.

And that’s the other and more important difference with If This Goes On…. Offred’s story is that of survival, of Illegitimi non carborundum, don’t let the bastards grind you down, of one woman’s attempt to stay true to herself even in the bleakest of oppression. Heinlein’s story on the other hand is the stirring tale of a second American revolution bringing an end to tyranny, largely through the efforts of one man.

That’s why The Handmaid’s Tale has stayed with me, whereas I’ve barely thought about If This Goes On… since I read it a few decades ago. Atwood’s story is so chilling because despite some of the zeerust in its future, it’s firmly rooted in the real world, even more so than classic dystopias like 1984. An unsettling book, but one any science fiction reader should read.