One of the things that has changed the most on the American comics scene between the time I was a hardcore collector in the eighties and nineties and now is the ready availability of reprinted material. It’s not just that you can count on most new series being released as a hardcover or trade paperback collection not too long after they first appeared in pamphlet form, it’s that increasingly, everything good that has ever been released in the past seventy years is available as well, as is much that isn’t (the world really need doesn’t the Magicman Archives). This is a huge difference, to be able to buy a series like Little Lulu, which I could only read about in nostalgic pieces in the fan press, as easily as you can buy the latest issue of Amazing Spider-Man.

This easy availability has deglamourised Little Lulu and other comics like it. Because these had been unavailable for so long, out of reach of average fans without access to well stocked back issue bins and the ready money to buy them, there was a certain mystique and glamour to them, and you poured over the small snippets you got of them in fan articles about them. And since these articles usually were written in the warm glow of nostalgia, Little Lulu got overpraised.

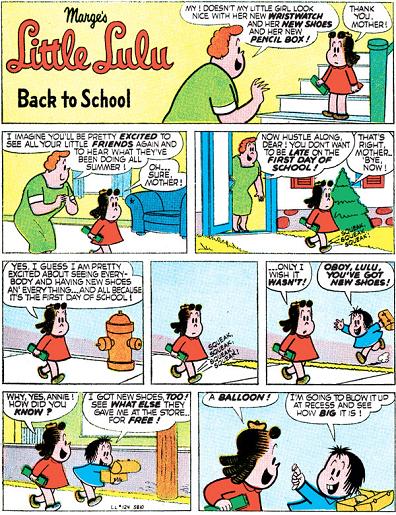

All of which is a roundabout way to say I was a bit disappointed with the random volume of Dark Horse’s Little Lulu series I bought cheap at the local bookstore. From everything I’d heard and read about it over the years I expected one of the great humour comics, but instead it was good, even excellent, but no more than that. The stories in The Burglar-Proof Clubhouse and Other Stories are funny and smart, but they are all variations on a theme and reading this in one go, it all got a bit repetitive. The art is okay, the best bits being the characters’ expressions; it’s all done as simplified as possible, which works well in a humour comic. The driving force behind Little Lulu was John Stanley, by all accounts a genius cartoonist, but at this point in the series he was working with assistants, in this case Irving Tripp.

The plots are pure formula. The first and most frequent sees Lulu outwitting the boys, especially Tubby, as he tries to swindle her into some scheme or other usually involving food, only to have it backfire on him. The other formula repeated throughout the volume is that of Lulu telling fantastical stories to Alvin, the little neighbour boy. The stories on their own are funny and witty, but you don’t need to read five of them in a row. But that’s the problem with reprinting comics that were always meant as disposable entertainment, where it doesn’t matter if next month’s stories are largely the same as last month’s, because nobody would’ve kept the previous issue anyway. And unlike e.g. Carl Barks’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, the suburban adventures of Little Lulu never quite lent themselves to such memorable stories as Barks could get away with.

All of which should not take away from the fact that Little Lulu was still one of the best American children’s humour comics ever written; it can’t be blamed for not living up to expectations created by nostalgia.