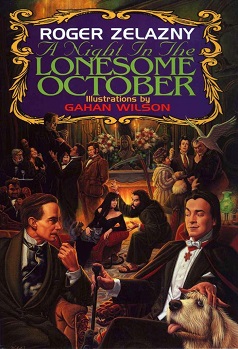

A Night in the Lonesome October

Roger Zelazny

Gahan Wilson (illustrator)

280 pages

published in 1993

A Night in the Lonesome October is a special book: except for the various collaborations he did with Robert Sheckley and others, it was the last novel written by Roger Zelazny before his death two years later. It was also a return to form. Zelazny had been one of the more interesting writers to emerge from American New Wave science fiction back in the sixties and had been a steady Hugo and Nebula nominee and winner in the sixties and seventies. the latter half of the eighties he had been mostly concerned with writing the second, lesser Amber cycle while in the nineties he mostly collaborated with other writers. A Night in the Lonesome October was the first new, solo non-Amber Zelazny novel since 1987 and more than that, it was good. As such it became a bit of a fan favourite among the people on the Usenet group rec.arts.sf.written, which resulted in a tradition of reading the novel day by day during October each year. This is possible because each chapter is a diary entry devoted to one day in October. I never took part in this, but this year I decided to try it when I wanted to reread it.

Set in Late Victorian London, A Night in the Lonesome October is the diary of a dog named Snuff, companion to a man called Jack who has a special knife. Yes, that Jack. He and Snuff are participants in the Game, held every few decades when there’s a full Moon on Halloween, October 31. There are some other, very recognisable characters taking part in this game: a certain Count, the Great Detective (of course), the Good Doctor and his self made man, etc. There are also some less recognisable people taking part in the game, like Crazy Jill and her cat, Graymalk, the latter as close to a friend that Snuff has in the Game. What the Game is about is only gradually made clear, but it is one played between two sides, Openers and Closers. Each player may not know which side the others are on; each player is basically playing on his own until the climax. Therefore there’s room for schemes to be drawn up, alliances to be made and betrayals to happen.