Asking for a friend:

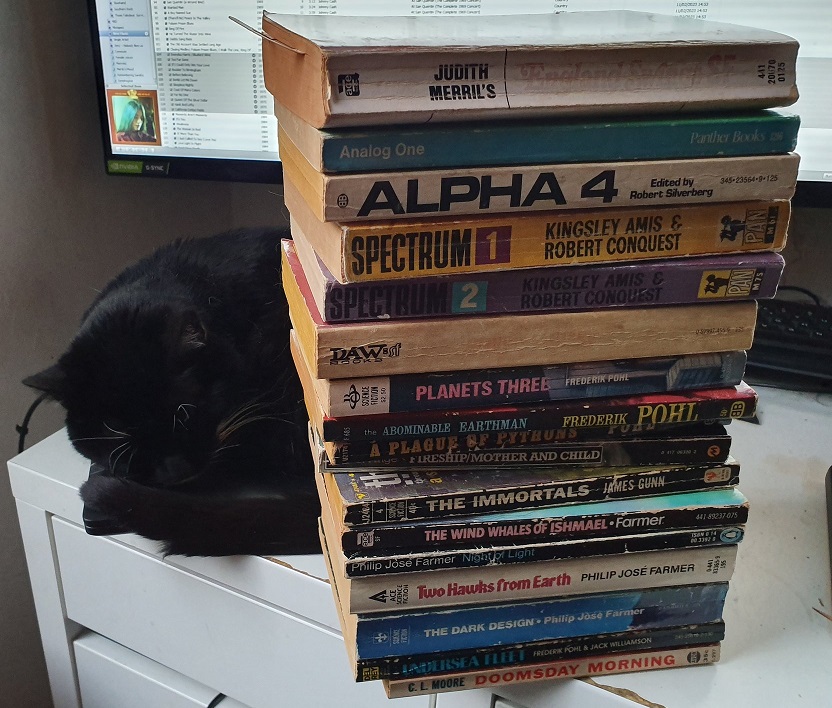

I was coming home to Amsterdam from the office in Utrecht and since the Metro was passing through there anyway, I thought to stop off at Spui on impulse and see if the American Book Center there had anything good. What I failed to take into account was that it was a Friday and the weekly bookmarkt was just in the process of wrapping up when I arrived. I’d come there often before Covid but this was my first visit in three years or so and had completely forgotten about it. It has a dozen to twenty or so antiquarian and second hand bookstores particpating, not all from Amsterdam itself. Most of what they bring along is of little interest to me, local history, Dutch literature and art books and the like. But every other stand or so might have a some gem hidden among its stock and if that fails, there’s always Magic Galaxies, as the name suggests, a store that specialises in science fiction. It’s where this stack came from. One of those stores you always see at a book market like this, always with a large selection of secondhand paperbacks next to the glossy Star Wars or Star Trek popup books, always for extremely reasonable prices. It’s amazing that I can still get sixties, seventies or even fifties sf paperbacks in good condition for under five euros. I used to think their prices were a bit on the high side, but they stayed roughly the same while everything else became more expensive.

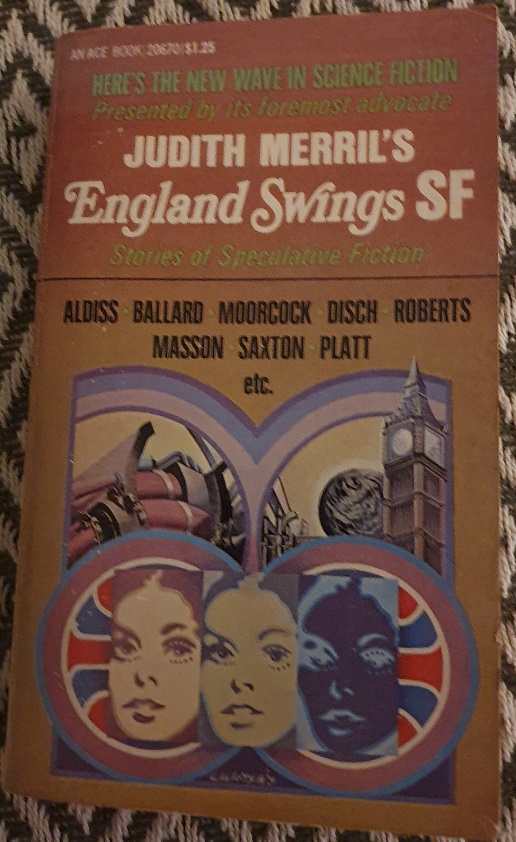

Among that stack of paperbacks is the perfect example of what I mean: Judith Merril’s England Swings SF, a book I’ve spent literal decades looking for. A book I’ve known about, have read about for decades I yesterday finally got to hold in my hands. England Swings SF is an incredibly important book in the history of science fiction. A key work of the New Wave, a defining statement of what New Wave science fiction was all about. It’s Judith Merril’s defining work, the jewel in the crown of her work as an editor. You know how important and controversial it was just from the publisher writing its own introduction washing its hands of the whole thing.

Though it may seem strange now, the New Wave was revolutionary, was controversial because it set out to deliberately undo science fiction’s dogmas, both literally and politically. Worse, as it originated in the UK and its most important early writers were British like Moorcock, Ballard and Aldiss, it also upset the natural order of America as the centre of the SF universe. When England Swings SF was released in 1968, the controversy had been raging for almost half a decade between the upstarts and the SF establishment. Like the British Invasion in rock music of the same time, the New Wave also reinvigorated established pulp authors like Robert Silverberg, who would write his best works after the wave hit. It laid the foundations for the more socially conscious and politically engaged science fiction of the late sixties and seventies. The New Wave completely changed science fiction — even if there still people even now denying this — and England Swings SF was its flagship.

Judith Merril herself had been doing a yearly anthology of the best science fiction from 1956, which had been become increasingly progressive in its definition of what science fiction is and where it can be found. Science fiction had until then always prided itself on not being literary, not being concerned with style or technique, too much character development, let alone politics or sex. Judith Merril played a huge role in changing that. As a writer, she’s best known for “That only a Mother…” (1948) and Shadow on the Hearth (1950), two early stories about nuclear war that focused on how it impacts regular people rather than techno wizardry. She moved to Canada and into academia in the seventies, still active in science fiction but no longer writing or editing much. Finally owning her most important work is one personal goal ticked off.