Not to undermine anybody’s faith in the liberalness of the Netherlands — you can smoke dope legally! Red Light District! — but yes, our police, just like in the UK or US, does have a problem with our darker skinned citizens as the short documentary above makes clear.

Policing

What being privileged is like

One fine evening, journalist Jamelle Bouie decides to sell his old tv to a friend and sets out to bring it over to them there and then, when considers what this would look like:

As I was getting ready to go, it occurred to me that this would be a terrible idea. Not because I would have been carrying a TV at 10pm down a quiet city street—I actually feel pretty safe doing that. But because I would have been a black dude—in a hoodie, no less!—carrying a nice-looking TV down a quiet city street at 10pm.

Had he been white, would he have thought about this? Jamelle himself thinks not, and I think he’s right. For myself, while I do occassionally wonder when doing something that could look dodgy, I’ve never been in a situation where I’ve been stopped by police because what I was doing looked suspicious. In fact, police officers here and abroad have always been respectful and polite to me, whenever I had to interact with them. The same really goes for any sort of interaction with authority; I’ve always been treated respectfully even when in the wrong, have more often than not been believed on my word when there was no real reason to do so, always gotten the benefit of the doubt when I needed it. In short, I’ve never had to worry about people judging me negatively just of how I look.

That’s something that’s incredibly powerful, in which I’m very lucky as I’ve done nothing to earn this respect, but which from the inside feels like the normal way the world should work; it doesn’t feel like I’m priviledged. This dichotomy, where it’s easier for those without these privileges to see how privileged those with them truly are, is I think responsible for much of the heat around internet debates about privilege.

On the one hand, people like me who enjoy these privileges need to make an effort to see them for what they are, while on the other hand they have never or rarely experienced the sort of harassement people without them encounter regularly. It makes it hard for us to believe them, even when everybody is arguing in good faith and it’s even harder to transform this intellectual understanding in an emotional one, to understand what it is really like to live without this privilege we take for granted.

That’s why simple, to the point and most importantly, unjudgmental post like Jamelle Bouie’s one here are so important, as they provide a way in which we can understand something of how other people live.

We Can Stop It

What I like about Scottish anti-rape campaign is that it approaches it in the way a drunk driving campaign would. So whereas with traditional campaigns the mephasis is always on rape prevention by the victim, this campaign is talking directly to potential perpetrators, using the same sort of techniques that helped make drink driving from something you bragged about to something you do furtively, if at all.

Not that rape is anywhere near as accepted as drunk driving once was of course, but rather that the way most of us, especially blokes, think about rape is about the stereotypical man in a dark alley physically overpowering a random woman. What this campaign instead is saying that actually, there are quite a few situations in which no physical force is used that are still rape or sexual assault, that consent is always required with sex and that decent, normal men know when it can and cannot be given.

What it does in short is to denormalise all these situations in which you can fool yourself that you’re not actually doing wrong in forcing somebody to have sex with you, by explicitely stating that no, having sex with a woman too drunk to stand up of her own accord is wrong. And it does it largely without putting the hackles up of its target audience, young men, who can get very defensive when talking about rape, for obvious reasons.

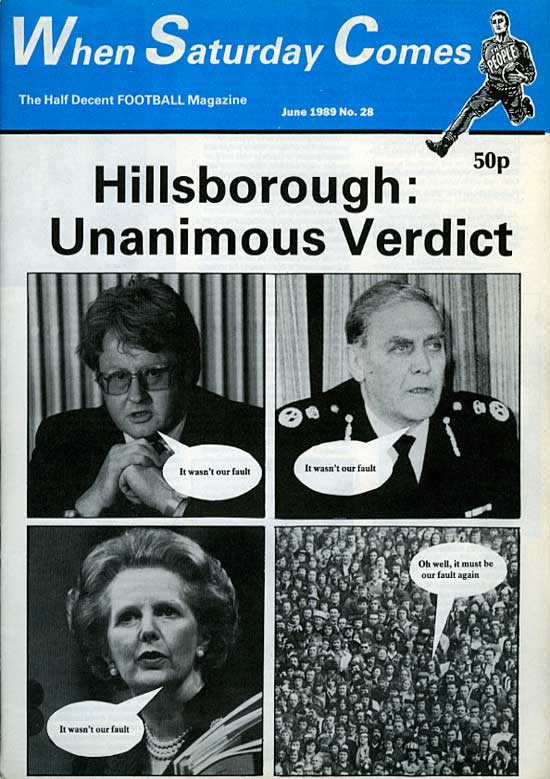

Hillsborough

Finally justice for the Hillsborough victims and it’s now official: there was a police coverup.

Ian Tomlinson killer walks off scotch free, has previous form

It took two years to to even get him before a judge, so it’s no great surprise that Ian Tomlinson’s killer has been acquited:

A policeman has been acquitted of killing Ian Tomlinson during G20 protests in London by striking the 47-year-old bystander with a baton and pushing him to the ground as he walked away from police lines.

The jury at Southwark crown court on Thursday cleared PC Simon Harwood, 45, a member of the Metropolitan police’s elite public order unit, the Territorial Support Group, of manslaughter following one of the most high-profile cases of alleged police misconduct in recent years.

Harwood told the court that while in retrospect he “got it wrong” in seeing Tomlinson as a potentially threatening obstruction as police cleared a pedestrian passageway in the City on the evening of 1 April 2009, his actions were justifiable within the context of the widespread disorder of that day.

Speaking outside the court, the Tomlinson family said: “It’s not the end, we are not giving up for justice for Ian.” They said they would now pursue a civil case.

It remains hard to convict a copper of anything, especially things done “in the line of duty”, even when said copper has previous form:

The jury at Southwark crown court, who took four days to clear PC Simon Harwood of manslaughter on a majority verdict, was not told that the officer had been investigated a number of other times for alleged violence and misconduct.

Harwood quit the Metropolitan police on health grounds in 2001, shortly before a planned disciplinary hearing into claims that while off-duty he illegally tried to arrest a man in a road rage incident, altering notes retrospectively to justify his actions.

He was nonetheless able to join another force, Surrey, returning to the Met in 2005. In a string of other alleged incidents Harwood was accused of having punched, throttled, kneed or threatened other suspects while in uniform, although only one complaint was upheld.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission described the chain of events around Harwood’s rejoining his old force before becoming part of its elite Territorial Support Group as “simply staggering”.

Emphasis mine. You wonder if the verdict had been the same if the jury had known Harwood had been investigated for assault previously, and was allowed to escape prosecution for it. But of course they were not allowed to know this:

The Metropolitan police attempted to keep the disciplinary record of PC Simon Harwood secret from the family of Ian Tomlinson, the newspaper seller he struck with a baton and pushed to the ground at G20 protests, it can now be reported.

Lawyers for the force tried and failed to argue that disclosing the litany of complaints about Harwood’s conduct would have breached his privacy, saying the officer’s disciplinary history did not have “any relevance” to Tomlinson’s death.

Harwood, 45, who was found not guilty of Tomlinson’s manslaughter on Thursday, had repeatedly been accused of using excessive force during his career, including claims he punched, throttled, kneed and unlawfully arrested people.

The jury in the trial were not told about the history of complaints, despite a submission from the Crown Prosecution Service, which argued that in two of the disciplinary matters he was accused of using heavy-handed tactics against the public “when they presented no threat”.

The application was rejected by the judge, Mr Justice Fulford, who said: “The jury, in effect, would have to conduct three trials.”

The establishment takes care of its own. If this had been an ordinary murder and the suspect had previous form, wouldn’t that have been admitted to court as relevant information? You would think so. Then again, a civilian who had been accused of assault and abuse would not have been allowed to escape prosecution in the first place…