I. Coleman has a point, comparing the hero of Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One with Peter Parker:

If you want a geek hero, look at Peter Parker. He likes Star Wars and obsesses over superheroes. He’s a nerd. He gets bullied for being a nerd. But his fondness for LEGOs isn’t what makes him a hero – that would be his heroism. His goodness. The fact that he’ll go out of his way to help an old lady cross the street. He knows what it’s like to get picked on, and instead of picking on others in turn, he chooses to stand up for the little guy no matter how hard it is. Peter Parker is what geek culture needs to strive to be every day. When we write an article or a videogame or a book, we should think “Would Peter Parker write this? Would he agree with what we’re saying?”

And conversely, I propose we should also ask “would Wade Watts like this?” And if the answer is yes, you should delete your draft, burn your script, drown the thing in white-out and start over. And it’s this test, more than anything else, that Ready Player One so catastrophically fails. Yes, it’s boring, poorly-written, and literally contains a ten-page list of titles of things the author likes. But it also fails the basic test of humanity, creating a character and a world so repugnant that I feel more than justified in saying it represents the absolute worst of nerd culture.

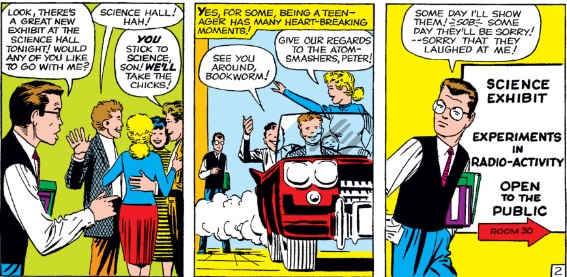

But there’s another way in which Peter Parker and Wade Watts differ, one that’s just as important as the one Coleman points out: what kind of nerd they are. It’s this difference that at least partially explains their moral differences as well. As we all know, Peter Parker got bitten by a radioactive spider that turned him into Spider-Man, but the reason he was bitten by that spider was because he went to a scientific exhibition, because Peter Parker was the kind of nerd who was really into science, who was studying to become a scientist. That’s why he was bullied, at a time when being a brainiac was not a good thing. There’s more than a hint of classism in the bullying, what with his principal tormentor being the popular, rich jock who could afford to tool around in a sports car, while Parker wore handme down clothes and thick nerd glasses. And that’s why he was bullied: he looked poor, he was a brainiac, he didn’t share the interests of the cool people nor felt the need to imitate them.

Wade Watts on the other hand is the worst possible sort of nerd, the one that thinks his (excessive) love of Star Wars and knowledge of eighties nerd trivia makes him special, gets him persecuted. He doesn’t create, he just consumes, never does anything original. He has a persecution complex but nobody’s persecuting him. His type is widespread among fandom, usually white men who’ve never had much hardship in their lives, but who’ve convinced themselves that a light spot of bullying during high school means the entire world is against them because of their brilliance. These are usually the same people who want to exclude anybody not like them — LGBT, women, PoC — from fandom, that only they are true fans though they never contribute anything. That’s the kind of fan who eat up flattering trash like Ready Player One.