These are the top ten comics in the Hooded Utilitarian International Best Comics Poll:

1. Peanuts, Charles M. Schulz

2. Krazy Kat, George Herriman

3. Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson

4. Watchmen, Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons

5. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, Art Spiegelman

6. Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay

7. The Locas Stories, Jaime Hernandez

8. Pogo, Walt Kelly

9. MAD #1-28, Harvey Kurtzman & Will Elder, Wallace Wood, Jack Davis, et al.

10.The Fantastic Four, Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, with Joe Sinnott, et al.

Notice anything? Yep, for an international poll it is very much dominated by American comics; even Watchmen, though created by two Brits, is very much in the American comics tradition. Worse, there’s no woman to be seen either, not until number 24, Fun Home, Alison Bechdel. In total there are just eight women on the list for a total of nine entries (Alison Bechdel being the sole woman to be mentioned twice), most of which are clustered in the lower regions of the list, having gotten on with just a handful of votes:

Fun Home, Alison Bechdel

Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi

The Dirty Plotte Stories, including My New York Diary, Julie Doucet

Dykes to Watch Out For, Alison Bechdel

Furûtsu Basaketto [Fruits Basket], Natsuki Takaya

Maison Ikkoku, Rumiko Takahash

Ernie Pook’s Comeek and the RAW Stories, Lynda Barry

A Drunken Dream and Other Stories, Moto Hagio

Moomin, Tove Jansson

I’m not going to blame the poll contributors for their appalling oversights, my own collection not being very gender balanced either and at least the Hooded Utilitarian editorial team are aware of this shortcoming, having asked Shaenon Garrity to redress the balance somewhat in a separate article. The gender skewedness of this list is just a symptom of a much greater problem, that comics as a medium is much too male dominated.

Part of that is mindset, a certain ignorance of readers and critics of female cartoonists, in which only a handful of currently active creators are well known, but the context and history in which they work is lost, each a singleton, the same problem we’ve discussedhere before regarding science fiction. Nobody is consciously suppressing women cartoonists, but there is still a systemic bias working against them, which polls like this bring to light. It’s so much easier to think of ten, hundred, thousand great male cartoonists who could arguably be part of the list than it is to find even half a dozen female cartoonists who could also be. It’s natural to think of sequences of influence like Noel Sickles -> Milton Caniff -> Al Severin -> John Buscema, but where does somebody like Marie Severin fit in?

But as Shaenon touches upon in her article, there are other barriers as well. The past ten years have seen an explosion of classic comics series, both newspaper strip and comic book being rediscovered and republished in nice, prestige editions, but how many of them have been created by women? Where are the classic female underground cartoonists to take their place amongst the Crumb archives? Where is the Daredevil Visionaires: Ann Nocenti? If the best work by women is not available, how can readers ever discover them?

Finally, and this is something that’s especially true for American comics, it might just be that the kind of work that really gets you noticed in comics is the kind of work that — certainly historical — has been the last available to female cartoonists. That’s the long form comic, the multiple decades old newspaper strip, the fifty issue plus comic book run, the one that needs time and dedication and self sacrifice. In Tom Spurgeon’s unrelated, intensly personal rant from earlier this week (which I found both moving and hard to respond to, if response is needed), he mentions at one point the “children of strip artists whose primary memory of their fathers and mothers is that person at a drawing board, desperate to get away for a few moments but deciding with an almost whole-body resignation to continue working while life-moment X, Y and Z unfolds nearby.” Which of course has always been easier for men than women to do, traditional gender roles being what they were and often, in disguise, still are. As Virginia Woolf once argued, before you could have great women writers, they need a room of their own, which goes double for cartoonists.

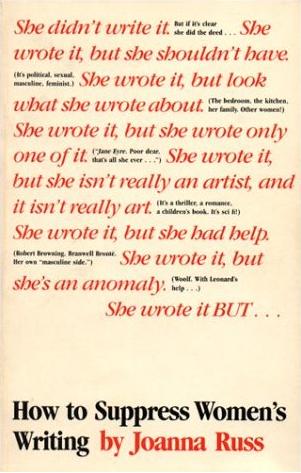

So, umm, yeah. It is understandable if bad that a list of the best comics a group of dedicated, clever critics can think of is such a sausage fest, but it’s just one symptom of a deeper imbalance, one not easily solvable, so what can you do? Well, perhaps comics needs to take the Russ pledge too:

The single most important thing we (readers, writers, journalists, critics, publishers, editors, etc.) can do is talk about women writers whenever we talk about men. And if we honestly can’t think of women ‘good enough’ to match those men, then we should wonder aloud (or in print) why that is so. If it’s appropriate (it might not be, always) we should point to the historical bias that consistently reduces the stature of women’s literature; we should point to Joanna Russ’s How to Suppress Women’s Writing, which is still the best book I’ve ever read on the subject. We should take the pledge to make a considerable and consistent effort to mention women’s work which, consciously or unconsciously, has been suppressed. Call it the Russ Pledge. I like to think she would have approved.