Andrew Weiss is asked is there “A hated story or story line you like?” and answers with John Byrne’s run on West Coast Avengers

Without trying to defend that nonsense (because, honestly, I can’t), I will say it regrettably overshadows an fairly entertaining and mildly innovative run of comics. For starters, it was John Byrne’s return to Marvel after a three year stint at the Distinguished Competition. The significance of that might be lost on kids born after 1980 or so, but for my demographic peers it was a Big Deal. Our memories of his X-Men and Fantastic Four and Captain America work was recent enough to give Ol’ Crankypants another chance.

Byrne’s run happened just as I was branching out from reading Dutch translations of Marvel series to the originals, as the local comic shop had finally started to carry them. First priority lay of course with all the series that had not been translated and WCA was one of them. For a noob like me, Byrne’s dynamism and willingness to shake up the status quo was great, even if I didn’t like what he was doing to the Scarlet Witch, who already was a favourite of mine. It was only later, when I’d more context to place his stories in that it became clear all his change was for the negative.

And it was only when I read an angry open letter Steve Englehart had send to Amazing Heroes that I realised that was probably deliberate. Byrne has always had a reputation for trashing everything he didn’t like in series he took over, prefering to strip continuity back to his own view of what Lee and Kirby did, rather than build on the work of other, lesser writers. As far back as 1982, when Byrne had only just started his Fantastic Four run, you had Len Wein and Marv Wolfman complaining about the changes Byrne made. In an interview for The Fantastic Four Chronicles special put out by Fantaco, Len Wein wrote: “I muchly resent what John is doing, I resent his implication that everything in the past 20 years hasn’t happened, that it’s still 1964.” Now on The Fantastic Four, Byrne created as much as he broke down, but on West Coast Avengers it was different. True, he brought back the original Human Torch and remade Hank Pym, Failed Superhero into Jump Suit Battle Scientist Hanky Pym, which was rather cool, but apart from that:

- Tigra reverted to a cat like state

- Master Pandemonium, from independent villain to lackey of Mephisto

- The Vision went from a crying android into an emotionless, “logical” Data clone

- Vison got a new, fugly piss yellow costume

- Scarlet Witch went insane and joined Magneto for a bit

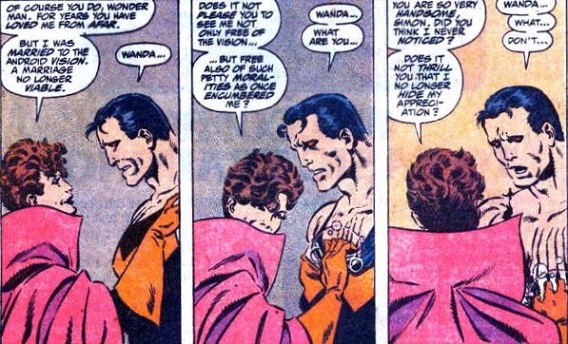

- Scarlet Witch went insane and molested Wonderman

- Wonderman meanwhile hat the hots for the Witch

- The Vision and Scarlet Witch’s babies? Never existed, just shards of the soul of Mephisto

Byrne started his run with issue 42 and left with 57 and from begin to end he set out to systematically demolish everything that Englehart had done with the Vision & Scarlet Witch. Personalities destroyed, marriage demolished, their kids retconned out of existence, etc. It’s hard not to see that as a deliberate vendetta against Englehart, especially in the light of the troubles he’d later ran into on his other two titles under DeFalco as editor-in-chief. Rereading it leaves a bitter taste in the mouth, seeing the creations of a writer who surely deserved better be torn down so brutally.