If there is an event that changed the Dutch as much as 9/11 changed the US, the Watersnoodramp, the flood disaster of 1953, was it.

This is a comparison I wouldn’t have reached on my own, but it is true. For those who went through the Watersnoodramp it was the biggest shock of their lives, perhaps an even bigger shock than living through World War II had been. That disaster after all was manmade, with convenient villains and which could be easily remade into a self flattering narrative of a plucky little country standing up to the might of the efficient, ruthless nazi hordes. But to be overwhelmed by nature, by the old enemy, the sea, the enemy we were supposed to have tamed and bound our will, suddenly showing just how fragile our defences really were: that shocked us to the core, that hit us in the national psyche.

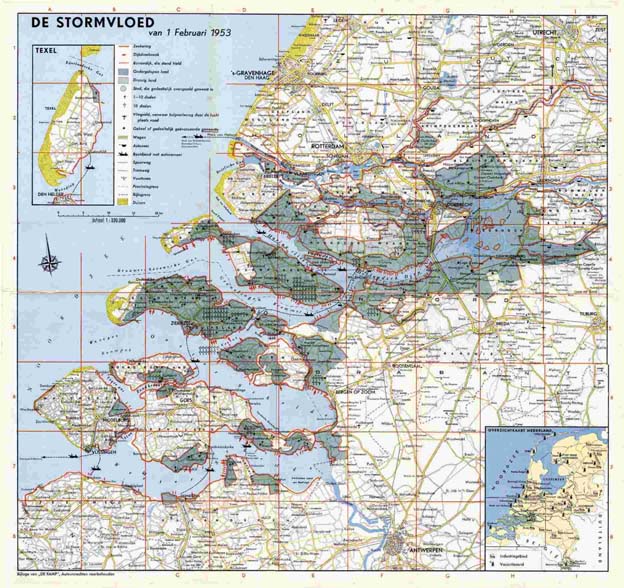

And like 9/11, while the disaster seemed to come out of the blue, the reality was that it had been predicted long before it happened. The southwest of the netherlands is a delta, where two huge rivers, the Rhine and the Schelde, come together and flow into the sea. Much of the land within the delta, in the provinces of Zuid-Holland, Noord-Brabant and Zeeland is artificial, won from the sea through centuries of patient dyke building and inpoldering; land reclamation. It lies therefore mostly below the normal water level already, only kept from flooding through the dykes. And because of the long coast line and the high costs of dyke strengthening, many of those dykes were strong enough to withstand normal flooding conditions, but not strong enough to withstand the extra strong surge of water that resulted from a combination of springtide and an unusually heavy storm on the North Sea.

To continue the comparison with 9/11, the response to the disaster was similar as well. Suddnely there was money and political will to implement the safety measures experts had been advocating for decades. But where after 9/11 this led to the TSA and the need to take your shoes off before boarding a plane, in Holland we go the Delta Works. Instead of merely repairing and strengthening the existing water defence works, instead the decision was made to radically alter and shorten the Dutch coastline, by closing up all those estuary mouths and inlets, except those that led to the ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp, of course.

But while we started off energetically to dam all the things, greater environmental awareness led to huge campaigns from the seventies onwards to stop the damming of the last remaining estuary, the Oosterschelde. Instead we got the stormfloodkering: a dam that’s normally open, but can close during springtides or at other dangerous times. This keeps the Oosterschelde at roughly the same salt level as it was at before the dam, keeps the normal tides coming in and out, hence keeping the ecosystem that was there before the dam alive. It was vastly more expensive than a simple dam would’ve been, but it’s the perfect compromise between safety and nature and has created the eight wonder of the world.