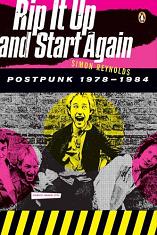

Rip it Up and Start Again

Simon Reynolds

416 pages including index

published in 2005

I’ve been looking for Rip it Up and Start Again in my local library ever since I got seriously interested in the whole post-punk phenomenon some two, three years ago. It had been namechecked by a lot of post-punk enthusiasts on music blogs and the like, so it was with some anticipation that I started reading. Fortunately, it didn’ disappoint me. Rip it Up and Start Again is an excellent overview of the response to punk in the half decade after the first wave of punk bands had crashed and burned.

Punk itself had gotten started around 1975, evolving out of raw rock bands like The Stooges, New York Dolls and MC5, through the New York club scene that produced the Ramones and finally landing in the UK where punk was embraced as a backlash against the dinosaur rock and prog rock indulgences of the mid-seventies. By the end of ’77, ’78 however, just as the general public became aware of it, punk had already exploded, with the Sex Pistols disbanding, The Clash selling out to Columbia and the Buzzcocks losing their lead singer. In the meantime a whole host of imitators had sprung up, with lesser and greater talent, mostly imitating what these three bands had done a year earlier, stultifying punk. But there were also other artists who took inspiration from the energy and d.i.y. approach of punk to go their own way: these were the artists that would make post-punk.

Post-punk as a label for a particular kind of music is therefore almost meaningless. For an approach to music however, it makes more sense. This of course makes it harder to define what is and isn’t post-punk. Reynolds sensibly limits himself to roughly half a decade, 1978-1984 of music, which he divides into two parts, post-punk proper and the rise of “new pop” and “new rock”. New pop and new rock being what happened when more commercially minded groups took post-punk music and adapted it for Top of the Pops. There are twentytwo chapters in total, each cataloguing a slightly different sort of rock or pop music.

Such an approach does not make for a good, chronological overview, but might be the only practical way of dealing with a field of music as ill defined as post-punk. Within its limits, Reynolds does his best to make clear how the groups and scenes related to each other and who influenced who. It helps that Reynolds is genuinely enthusiastic and knowledgeable about it all. Nevertheless, an increbible number of bands and artists are paraded in front of the reader, introduced, dissected and left behind as Reynolds moves on to the next chapter. In the end, it was all a bit much; both Reynolds and the reader start flagging.

Before that happens though, you get a good introduction to what happened in Britain and the US in the late seventies and eighties, after punk had crested but the energy it had freed was still present. The post-punk era gave us an incredible variety of good bands –to name just some of my own favourites, Gang of Four, The Pop Group, Joy Division/New Order, The Teardrop Explodes, Echo and the Bunnymen, etc. — and Reynolds does a good job of establishing the key points of each one. A great book to be inspired by, to seek out new bands. Recommended for anybody interested in post-punk.