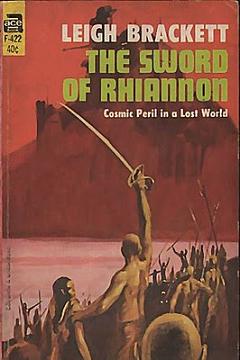

The Sword of Rhiannon

Leigh Brackett

141 pages

published in 1953

You may think you don’t know Leigh Brackett or read any of her stories, but you’re wrong. If you think The Empire Strikes Back is the best of the real Star Wars movies, you have her to thank for it, as she wrote the original screenplay, just before she died. This is no fluke either, as her screen writing career is almost as old as her science fiction career. She started off on The Big Sleep together with William Faulkner and has worked on other well known movies like Rio Bravo and The Long Goodbye. And with her long She knew her way around a film script; combine that with her long experience writing science fantasy for pulp magazines like Planet Stories and you know why Empire is so much better than any of the other Star Wars movies.

If you liked Empire than the good news is that Leigh Brackett is even better when working on her own stories. Though she wrote other science fiction, she’s best known for writing planetary romances (or science fantasy) in the tradition of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Her best stories are set on the Mars of Burroughs and dozens of pulp imitators, a dying world turned into a worldwide desert as its seas dried up, with a highly evolved but degenerated civilisation clinging to life through an elaborate system of canals, now turned into a new version of the Western frontier as Terran adventurers and never do wells come to try their luck. Brackett’s Mars is more than just a pulp adventure setting though. Her best stories leave you with a sense of melancholy and loss, perhaps nowhere more so than in The Sword of Rhiannon, “a hymn to the lost past of a Mars that never was” as Nicola Griffith put it in her introduction to a recent reissue.

The Sword of Rhiannon was first published in 1949 as The Sea Kings of Mars in Thrilling Wonder Stories and it’s under this title you can find it in the Leigh Brackett volume of the Gollancz Fantasy Masterworks series (rather than in the Science Fiction Masterworks it should’ve been). As with most novels of this period it’s quite short and the plot is fairly straightforward. Matt Carse is a human adventurer with a background in archeaology, who gets the opportunity of a lifetime when a lowlander Martian thief promises to lead him to the tomb of Rhiannon. Rhiannon being the Martian equivalent of Satan, the Fallen One, the Cursed One, the rebel who the Quiru gods of Mars had left behind when they had left the planet for other realms. Carse doesn’t believe all this of course, thinking Rhiannon only a myth, but one that might have a kernel of truth and the discovery of his tomb will make him a rich man.

Of course he’s double crossed by the same thief that let him to the tomb, thrown into a trap inside, a “a big brooding sphere of quivering blackness”. Passing through this he finds another mind touching his own and after what seems an eternity he emerges on the other side of the room, with no trace of his betrayer. Worse, he finds himself locked in the tomb amongst signs that not all is what it seems. When he manages to dig himself out he finds himself no longer in the ruins of a city abandonded for a million years, but in that same city at the prime of its life, on a Mars that still had its seas. A stranger in a strange land, Carse quickly learns all of Mars is at war, a war between the evil forces of the Sark and their half human, half serpent Dhuvian “allies” and the still free Sea King and their Wing Men and Swimmer allies. Seen as the incarnation of Rhiannon and mistrusted therefore by the Sea Kings who have his sympathies, Carse is the key to winning the war, if they let him.

Apart from Matt Carse/Rhiannon himself, the main characters aren’t fully fleshed out, largely pulp stereotypes. There’s Boghaz, the fat, amiable rogue and thief who would cheerfully rob Carse yet is loyal at heart. There’s the reluctant villainess of the story Ywain, the princess-heir of Sark, proud, fierce but ultimately unable to resist Carse’s masculine power, there are the hearty noble barbarian sea kings, not to mention the serpentine Dhuvians oozing evil. The Sword of Rhiannon is still mired in the pulp sensibilities of the magazines Leigh Brackett wrote for, where morality is black and white, where there is such a thing as racial character and a whole race can be irredeemably evil, where men are men, women are women and a proud woman like Ywain secretly yearns for a strong man like Carse to “master” her. Leigh Brackett certainly isn’t a feminist writer here, though there isn’t the rapeyness of some of her male colleagues.

What sets The Sword of Rhiannon a touch above other pulp adventure stories is both Brackett’s writing and that elegiac sense of loss that comes across through it. At the end of the story Carse returns to the Mars of his own day, leaving a still living world for one that is slowly dying. He may have saved Mars from the tyranny of the Dhuvians, but its ultimate fate is still fixed…

ResoluteReader

June 23, 2011 at 5:08 pmSometimes I read a review in passing and realise that I just have to dig out the authors entire back catalogue. I’d not heard of Leigh Brackett. Thanks for bringing her to my attention.