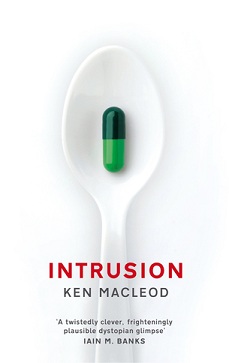

Intrusion

Ken MacLeod

387 pages

published in 2012

Over the past five years Ken Macleod has written a series of standalone novels that each in their own way have dealt with the post-9/11, post-War on Iraq 21st century and what it might evolve into. Intrusion is the latest in this series. Where MacLeod had always been a politically minded writer, his last few novels (The Execution Channel, The Night Sessions and The Restoration Game) were all directly rooted in current political realities, especially the socalled War on Terror. Intrusion continues this trend, but this time swapping the War on Terror with the nanny state.

And at first Intrusion feels like a novel from an alternate universe, one in which Labour didn’t lose the elections and had continued on its pre-9/11 social engineering course rather than by distracted by Blair’s foreign crusades. Britain’s nanny state has been turned up to eleven, driven by ubiquitous realtime surveillance and monitoring technology and increasingly finetuned social law. MacLeod has taken everything New Labour and the ConDem coalition have been guilty off in the past decade and a half regarding tackling socalled social problems: increasingly absurd health and safety laws, the liability adverse local bureaucracies, the enthusiasm to seek technofixes for ingrained social problems, the idea that you can force or nudge people into healthier lifestyles through banning or taxing their vices and extrapolated what it would look like a generation or so into the future. It’s a world in which most women wear monitor rings to make sure they’re not pregnant and if they are, are not smoking or drinking or going to places where toxins might be that could harm their unborn child, where ipso facto most women work at home as so many workplaces are not safe for their (potential) offspring due to e.g. trace remnants of cigarette smoke.

Such is the case for Hope Morrison, nee Abendorf, married with one child and one on its way, who for the most part accepts this as the way things are, neither bad nor good. What worries her far more is the Fix, a simple single dose pill that eradicates many common genetic defects and vulnerabilities. She doesn’t agree with it, hadn’t taken it for Nick, her first child nor does she wants to take it for this child. Worse however, she has decided against it not from any sort of religious dogma, but just because she’s uncomfortable with it. She had made this choice but doesn’t want to justify her choice to anybody, which is something the system has difficulties with. It is no wonder therefore that she’s increasingly pressured to either give in and take the Fix or to provide a proper, regulated reason for rejecting it.

Intrusion‘s plot is all about how Hope and her husband Hugh, a carpenter working with carbon fixing, self shaping New Tree wood, try and escape this pressure, trying to live their own lives within this system without either being grind up in it or compromise more than they have to. They’re not rebels set out to overthrow it, they’re just ordinary people who on one particular point want to make their own choice and want the freedom to make it without having to explain it in an approved, sanctified manner. But as an encounter with Hope’s local MP makes clear, when she tries to get him to help her, this is just what not only cannot be allowed to happen, but which the system as a whole is incapable of allowing: people cannot be free to make their own choices, as they might make the wrong choices:

“But it doesn’t feel very free,” Hope said, “having other people make your choices for you.”

“It feels a lot freer than making the wrong choices,” said Crow.

[And a few paragraphs later]

The government isn’t makeing choices for anyone. Like I said, it’s enabling people to make the choices they would make for themselves if they knew all the consequences of those choices.”

Which is something that could probably have been inserted in any Labiour manifesto of the past twenty years without raising too many eyebrows. On one level, as with the admonishment the MP bites off to Hope that if she’s that libertarian, why she doesn’t go and live in Russia, it’s incredibly funny; on another this image of the future is chilling as it’s so plausible, so clearly already starting to happen. The social free market ideology MacLeod has invented is something that could easily be reinvented by Labour (or perhaps the LibDems) for real.

If this isn’t chilling enough, Macleod doesn’t ignore the Labourite War on Terror and its security apparatus either. All through Intrusion there are hints that the powerful nudges the government can dish out often can turn into shoves, which is confirmed as one secondary character is picked up from the street, shoved in the back of a police van and chemically interrogated all without being arrested, but she is left with the number of a trauma helpline she could call. And all that because while she is Brazilian, she looks Indian and hence is suspicious in the climate of the Warm War, where the new Free World of America, Britain but also China and Iran confronts the new old villains of Russia and India as these refuse to confirm to post-Climate Change morals. This it seems is one of those things that are invisible to people who don’t fit a particular profile and ar therefore not hassled, but are common occurrences to those that do.

Intrusion is a bleak novel, a pessimistic novel, though not without a certain grim humour. It’s the most pessimistic I’ve seen MacLeod, even the sf macguffin driving much of the plot not offering much hope. It’s also a novel that calls back to his earliest novels, the Fall Revolution series and especially The Sky Road. You could read it as a dystopia, with the lazy comparisons being with 1984 or Brave New World, though it’s a much more realistic sort of dystopia than those two. In the end, unlike them, nobody is in charge but the system and the system has no consciousness, is unaware software rules and linked up databases driving surveillance and interference.

This is an awareness that slowly builds up through the novel, just as MacLeod only gradually reveals the world in which it is set and it makes a mockery of the grandiose speech one tertiary character gives to the woman who was assaulted by the police about how even the activists opposing the system actually serve it, how her assault was just a notification that it knew of her. It demands a consciousness of the system that it just doesn’t have.

Which is perhaps the most frightening idea in Intrusion.

No Comments