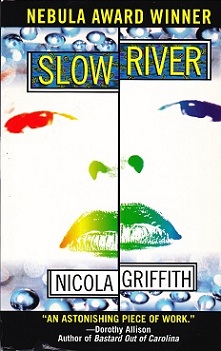

Slow River

Nicola Griffith

343 pages

published in 1991

Everybody knows about the Bechdel test now, don’t they? Introduced in Dykes to Watch out For, it’s a test to see if a given story meets a minimum feminist standard: a) does it have at least two women, who b) talk to each other about c) something else than a man? It’s a good way to think differently about the movies you see or the books you read, to see how common it is for a story to have only male characters, or only a token female character, sometimes as prize for the hero. Having a story with only male characters is normal, having one with all or majority female characters is the outlier, can get you shoved into a women only ghetto like romance or feminist literature.

This is true in science fiction as well as mainstream literature, which made reading Nicola Griffith’s Slow River so interesting. It’s her second novel, also the second of her’s I’ve read and like the first, the cast is almost exlusively female. But where that one was set on a planet where men had died off due to some handwaved plague, this one takes place in near-future English city that for once isn’t London. I’m not sure whether Nicola Griffith made this choice of cast deliberately, or it just happened naturally because of the story she wanted to tell, but it works.

The story Griffiths wants to tell in Slow River is that of Lore, younger daughter of a wealthy Dutch family, who’ve made their fortune with building conservation and waste treatment plants. Lore has led a privileged and sheltered upbringing, up until the moment she’s kidnapped. That was three years ago, three years since Lore escaped from her kidnappers and found herself naked by the river that runs through the middle of the city and met the woman who called herself Spanner. Lore isn’t keen to go back to her family — why this is so is explained over the course of the story — and she moved in with Spanner, but now, three years after, she feels it’s time to stand on her own two feet and leave Spanner and her self destructive ways behind her.

Spanner you see is a small time criminal, somebody who steals information, can provide you with a trusthworthy fake identity and hacks reprogrammable slates in the best cyberpunk tradition, at the fringes of organised crime but a small fish in a big pound. She may have rescued Lore and Lore will always be grateful for that, but she herself isn’t a nice or particularly sane person and Lore could see that sooner or later it would catch up with her.

Lore herself is not quite healthy in her own skin either, otherwise she would’ve gone back to her family. But she neither wants to nor dares too, as too much has happened for her to go back. Instead she tries to build up a new life as a manual worker at a waste treatment plant in Hedon Road and gets involved with the day to day problems of being on the night shift of the conservation plant. The details of which, while the least dramatic, are also amongst the most interesting in the novel; Griffith has clearly done her homework and is good at dropping in convincing sounding details of the work.

The plant is also where we meet the third woman, Magyar in the “love” triangle between Lore, Spanner and Magyar. If it’s Spanner whose shadow Lore wants to get out under, than Magyar is who Lore wants to win the approval off. Tough, no-nonsense, she’s the shift leader at the waste treatment plant and almost from the start suspicious of Lore.

In between this main story, there are also the stories of Lore’s three years with Spanner, trading in the depence on her family to a sort of independence, as well as the story of her youth up until the kidnap. What I only noticed about a quarter of the way in is that these three interwoven stories are actually written in three different viewpoints. There’s the first person point of view for the present, tight second person focus for the years with Spanner, while the chapters focusing on her family are in a much looser second person focus. The difference is that in the first form of second person focus we’re still inside Lore’s head most of the time, with the text refering her as “she”, while the second form, we see her from the outside, as “Lore”. It is of course symbolic for her growing up, maturing, going from what others see her as, to what she sees herself as. A coming of age story that is not nearly as obvious as most such are in science fiction.

In other words, Slow River is quite strange for a science fiction novel: a largely female cast with the plot driven by their individual concerns rather than outside concern driven, which is quite sophistically written with three different viewpoint styles and where the science on display is ecological, environment enginering. It’s no wonder it won a Nebula. A great, satisfying novel by a writer who should be much more well known than she is.

Slow River, Nicola Griffith | SF Mistressworks

January 8, 2015 at 7:01 am[…] This review originally appeared on Martin’s Booklog. […]