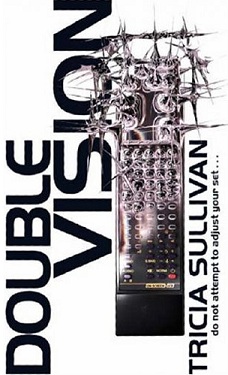

Double Vision

Tricia Sullivan

377 pages

published in 2005

Karen “Cookie” Orbach’s life seems fairly mundane when looked at from the ouside: she hasa job with the Foreign Markets Research Division at Dataplex Corp, does karate as a hobby and a weightloss exercise, has no boyfriend or partner but does has a cat, eats too much out of stress and for comfort, reads a lot of science fiction and fantasy. The thing is, Cookie is psychic and while she did offer her services to the police, who believes an overweight Black woman reading too much Anne McCaffrey? Luckily Dataplex did see her potential and engaged her as a Flier, somebody who can see what’s happening in the Grid, an alien world Cookie can see when she watches television, where see can monitor the progress of the military expedition there and work as a reconnaissance flier for Machine Front, which coordinates the offensive.

Cookie’s mundane even boring life stands in shrill contrast to the dangerous glamour of the Grid. Despite being only a passive observer there, it is much more real to her, much more interesting. It matters, while her routine life outside of it doesn’t. It’s a feeling that any science fiction or fantasy fan can recognise, that idea that whatever fantasy world floats your boat is more important than what happens in real life, but for Cookie that fantasy world is real — or is it?

As a science fiction reader you’re obviously biased towards the strange, the potential hallucination to be real, even if there’s a long tradition to use this against the reader. In Double Vision you start off with the default assumption that what Cookie experiences is real, only for Sullivan to sow doubt in your mind as certain inconsistencies become clearer. For example, if the scouting she does in the Grid is so important, why is it that her boss is only interested in which brands she heard mentioned by the soldiers? What is she really used for?

In real life Cookie is not a standard science fiction hero either –being Black and female for starters– as she’s self effacing, content to go along to get along, struggling with her weight, meek but with outbursts of anger. She comes in her own in the end, gets stronger, both physically through her weight training and karate classes and mentally through her experiences in the grid, but it doesn’t gain her much. At the end of Double Vision she’s in prison for having assaulted her sensei in a fit of anger of his coverup of the sexual assault on her friend.

Said sexual assault is the weakest and most problematic part of the book, as it hinges around certain racist cliches about Asian men and their lust for white women. It takes place in the context of a visit by the Okinawan masters of the karate organisation Cookie’s dojo belongs too, who are feted by the dojo’s owner and his students, when one student remains behind to learn more about the history of karate, or that’s what she thinks in her innocence: she’s blonde and tall, he’s short and dark and speaks broken English. It’s blatant enough that even I noticed it, which doesn’t always happen with racial or sexist imagery.

Fortunately, Tricia Sullivan is a writer honest enough to to recognise these racist undertones in hindsight and decent enough not to be happy with this:

I was working out my personal issues with karate on the page. I had been with a group of Americans travelling to Okinawa to train, and while we were there I learned a little about the American presence on the island. It was only years later that I began to hear of the abusive behaviour of US soldiers toward the Okinawans—especially the women. But I didn’t think this through when I was writing. I’m ashamed of the fact that when I flipped the roles around in Double Vision and made the Okinawan masters visitors to the US (which I did for storytelling convenience) I completely failed to see the ways in which I was reversing the more typical scenario of US male sexual assault upon Okinawan females. I couldn’t see it at the time. I was too busy trying to deal with the way it felt to write about what had happened—the karate side of things more than the sexual side, to be honest—and so I didn’t look at the material properly.

This is exactly the sort of honest examination of your own privileges and innate biases that you should engage in when called upon them, yet we rarely see. I can only wish I would be so honest and fair in similar circumstances.

Though this is a blemish on the novel as a whole, I think it’s still a worthwhile book to recommend. I can’t really speak to the validity of Sullivan’s portrayal of Cookie and how fair it is, being neither Black nor a woman, but certain parts ring true. What it feels to be a large person, a fat person, how food, especially bad food, junk food, plays a role in your life as a substitute, a placebo for everything you can’t get because of your size, knowing full well that it doesn’t help. What Sullivan also hits just right is that feeling of just living your life waiting for something important to happen to you, living vicariously through science fiction.

Furthermore, Double Vision is a quietly feminist science fiction novel. Where in real life Cookie daily experiences some sexist jab or other, in the Grid there are no men, only women, as the men fucked up, leaving it up to them to clean up their mess. Everything in the story revolves around Cookie’s relationships with other women. Of the men in the story, only two are sympathetic towards Cookie, with only one having a real friendship with her; the majority are disinterested bystanders or active harassers. As with Nicola Griffith’s novels, this is done so naturally that you don’t notice how different this is from your usual science fiction story until you actually pay attention to it.

In short, Double Vision is flawed in some aspects, as Tricia Sullivan has acknowledged, but it has its heart in the right place and ultimately overcomes its flaws. Recommended.

No Comments