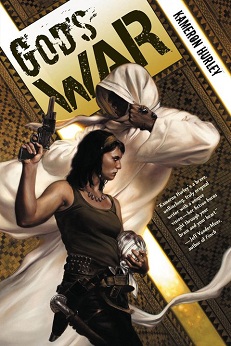

God’s War

Kameron Hurley

286 pages

published in 2011

The main problem with God’s War is its setting. Kameron Hurley’s debut novel is set in an unspecified far future, on the alien planet of Umayma, featuring an unending, religious war between Nasheen and Chenja, Umayma’s biggest nations. The war has warped both nations’ societies, with each country’s men either dead or at the front, leaving only the very young and very old at home. Despite both societies’ innate conservatism that has left women to take up the slack, having to take on traditional male roles, resulting in what’s best called a violent matriarchy in Nasheen, with women in all positions of power and the men constantly being sacrificed at the front. Nyx, its protagonist, is a brutalised, aggressive, scary woman, a deliberate attempt by Hurley to create the female equivalent of somebody like Conan while the background against which Nyx plays out her story was meant to show how a brutal, violent hierarchical society doesn’t magically become better because women are now in power, how easy it is for women to keep perpetuating the same violence and abuse as the men, just with different people in the victim and oppressor roles.

It’s an interesting concept, but the execution is troubling. Because while it is set on another planet far in the future and the politics and religion that’s being fought about is fictional, the images that Hurley creates are very familiar, because the religion she creates looks a lot like Islam, veiled women, multiple daily prayers, holy book and all, with the war and the societies it has left in its wake familiar from what we’ve seen on the news from Iraq or Lybia or even Chechnya. The landscapes are all desert landscapes, the cities are Middle Eastern, with mosques and minarets, often broken, often bombed out. As Tariqk put it, it’s as if Hurley “took every stereotypical Arab world depiction & TURNED IT TO 11”. It’s this orientalism that fails this novel, this inability to do more than use orientalist stereotypes, that reduces it to just another grim and gritty adventure story when it could’ve been so much more.

God’s War starts with one of those opening sentences you can only have in science fiction: “Nyx sold her womb somewhere between Punjai and Faleen, on the edge of the desert“. It sets the tone for the rest of the book, in the brutality and the matter of factness with which the protagonist, Nyx engages in, both against herself and others. It also hints at the gore, the sheer organic background of Nyx’s world, where the omnipresent all terrain pickups, bakkies, are run on bug cisterns, half or wholly organic power plants and blood and tissue are currency. It reminded me at first of China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station, but that novel was far more baroque in the way it used biological constructs in its background.

The story that starts with that great sentence in itself only turns out to be prologue, an extended action series in which Nyx flees from at first undefined to us enemies, while following a note, a boy who had deserted from the front, who was possibly infected by a delayed action disease, who she needs to neutralise and kill. At that point Nyx still is a bel dame, a government sanctioned killer/bounty hunter, but by page 40 she has gotten her note, her enemies have caught up to her and she’s dumped into prison for a year. When she gets out she’s no longer a bel dame, but just a common mercenary, which is where God’s War‘s story really starts.

In between the first and second parts of God’s War several years have passed and Nyx has assembled a team of bounty hunters. Rhys, already met in the prologue, is one of them. A draft dodger from Chenja, he’s a failed magician with just about magical talent to be useful to Nyx, but in a peculiar way he’s also her conscience. Rhys is a deeply religious man and Chenja is slightly more conservative even than Nyx’s Nasheen. In the latter, of necessity women have taken over every role that traditionally would’ve been male, as all men are on the front until they’re forty, few surviving that long. In Chenja the same is also true, but hidden more behind a facade of normality. It makes Rhys deeply uncomfortable to be in the more “liberal” Nasheen, to see people not adhering to what he believes is right. He comes over as a bit of a prig, a bit stupid even where his religion is concerned, one plot point made possible only by his decision to go to prayer in the middle of enemy territory.

Yet while Rhys is in some ways the conservative foil for Nyx to put down, with Nyx’s views on religion as bunk more likely to be sympathetic to the reader than Rhys’s staunch beliefs, he’s not undeserving of our sympathy. He’s as much a victim of the war as she is, having been beated up a couple of times in the street, as well as sexually abused in encounters with the Nasheen security forces. He pays the price for being a man, a Chenjan man, safely away from the front, for being who he is, just like the rest of Nyx’s crew does. Like e.g Taite, homosexual in a world where most countries punish homosexuality with death (another thing taken from what we imagine Islamic countries are like). All of Nyx’s crew is damaged in one way or another, products of a relentless war, Nyx and Rhys the most. Their relationship is the heart of the story.

Most of which, as said, is relentlessly grim, things starting out bad for Nyx and getting steadily worse and though she pulls some sort of victory out of the bag at the end, the cost is high. It makes for a hard read at times and I’ve found myself putting it down more often than I usually do. What also made it hard going was that orientalist, pseudo Middle Eastern setting. Kameron Hurley in one way made a good attempt at creating a fur future setting with no obviosu ties or references to 21st century Earth, yet then undermined it by using these stereotypes of Islamic religious fundamentalism, by the veils, the multiple daily prayers, the stonings for homosexuality, calls to prayers moving “in a slow wave from mosque muezzin to village mullah”, the sun bleached yellows and browns of the world and the war pocketed, partially destroyed towns and cities echoing the pictures we’ve been seeing on our tv screens coming in from Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria.

The setting for me is what in the end makes God’s War a failure, as shows a fictional, far future religion set on an alien world, yet in terms that are particular to the decade we’ve just lived through. It jars, it’s lazy and perhaps any attempt at creating a religious war would’ve had echoes of our recent history in it, but surely Kameron Hurley could’ve done better?

No Comments