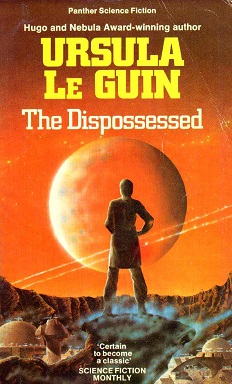

The Dispossessed

Ursula K. LeGuin

319 pages

published in 1974

After the Earthsea trilogy and of course The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed is arguably Ursula LeGuin’s most famous novel. It was one of a small group of novels in the early seventies –including e.g. Joanna Russ’ The Female Man that took the American New Wave and science fiction as a whole into a much more explicit political direction. It’s a novel that’s still controversial today, or at the very least can still lead to heated debates. The Dispossessed has been hugely influential in radicalising whole generations of fans, while there are plenty of conservative science fiction fans for whom its is a symbol of everything that went wrong with science fiction in the seventies.

The Dispossessed, firmly in the utopian tradition of Herland and looking Backward is a travelogue, set on the double planets of Urras, stand-in for seventies America and Anarres, the “ambiguous utopia” of the subtitle. The protagonist Shevek is a brilliant young physicist whose passion for science leads him to travel from his anarcho-syndicalist home planet to Urras because there he hopes to find the support he needs to finish his thesis. In alternating chapters we get to see his journeys to and on Urras as well as his upbringing and life on Anarres.

Anarres is a harsh world, barely liveable with limited resources; it’s dependent on exporting certain rare minerals and metals to Urras to earn some of the support it needs to keep going. Settled two hundred years before in a grand bargain to prevent an anarchist uprising on Urras, the resulting society has been shaped both by the necessities of life on Anarres as well as the ideology of its founders. The result is a classless, government-less society in which everybody is equal and free to do what they want to, yet in everyday life the emphasis is very much on keeping consensus and sharing. There’s little luxury but a lot of camaraderie, everybody working together to survive on an unforgiven world. Or at least, that’s the theory. The reality is slightly different.

There’s no government on Anarres, but there is Production and Distribution Coordination (PDC), grown out of the crisises Anarres had to deal with, which slowly metastatised into something resembling a professional bureaucracy, including politicing and power struggles. The PDC is responsible for coordinating everything that’s needed to keep people alive, for example assigning people to the jobs that need doing. This is supposed to be done based on the needs of the community as a whole as well as the wants and skills of the individual, who is free to reject the assignment or request another, but in practise some more …difficult… individuals find it hard to get assigned to anything but manual labour.

More insidiously, consensus thinking keeps most of the population in line: you’re free to do what you want as long as your neighbours don’t mind. People like Shevek who are slighly different or slightly awkward at fitting in are punished for it, in more and less subtle ways. In an early scene, the eight year old Shevek has independently discovered one of Zeno’s paradoxes, but when trying to explain it is accused of egotising rather than sharing. In another, a man with a similar name to him attacks him without anybody interfering. Shevek accepts that as the way the world works, any dispute being solely between the two people involved and no business of anybody else. In these and other ways a rough consensus is kept, with those unwilling or unable to keep to it punished in informal ways.

As said, Shevek accepts all this, as it is after all the world he grew up in. While it has its flaws and while life on Anarres can be tough due to the harsh conditions of the world by the end of The Dispossessed it’s clear that it is far more honest and fair than life on Urras; people might starve but they starve together.

When Shevek arrives on Urras he is first struck with the richness of it. The world itself is much richer and friendlier than Anarres, but there’s also the wealth of the people at the university, the fact that he is given several rooms for his own personal use, without the need to share with anyone. Or just the simple fact that Urras’ society is rich enough to throw away paper rather than recycle it. It’s only after he gets used to this richness that he’s able to see the poverty it hides, the sickness that made it possible. Urras is of course a slightly exagerrated view of American society in the seventies, including brutal repression of antiwar and trade union protest as well as a cold war between the two most powerful nations on Urras, one the capitalist nation of A-Lo Shevek finds himself in, the other the vaguely communist nation of Thu.

The way LeGuin builds up the contrasts between Anarres and Urras is clever, as she shows the latter at its most desirable, the former at it least in the first chapter, starting with Shevek being driven from his home and welcomed into the opulence of Urras. She’s also careful to make neither society wholly bad or wholly perfect: the appeal of Urras’ wealth to Shevek is understandable, while despite its flaws, it’s also clear Anarres’ society is superior. This may be ambiguous, but it’s still an utopian society, if a very seventies one with its emphasis on shared suffering rather than shared wealth. The politics of The Dispossessed are well thought out, counsciously worked out, without ever getting preachy. Unfortunately however it’s all let down by a huge but forty years on glaringly obvious blind spot: women.

Because the only two major female characters in The Dispossessed are Shevek’s patient, quietly supportive wife and the woman he sexually assaults on Urras. Of course there’s also Odo, the founder of Anarres anarcho-syndicalism, but she’s there to play the role of safely dead secular saint for the Odonists. Though LeGuin contrasts the even more patriarchal than actual seventies America Urras with the supposedly equality of the genders on Anarres, seeing the actual female characters with such limited roles, only there as props for the protagonist, completely undermines this.

At least for modern audiences. Because I’m not sure how noticable this was to contemporary audiences, back in the days when science fiction was largely a sausagefest and it was no more than natural that even women writers would have male protagonists and women where there only as wives and girlfriends. The Dispossessed was neither the first nor would be the last novel to earnestly talk about equality while undermining itself with what it actually does. This failure shouldn’t necessarily stop you from appreciating what The Dispossessed does, but does show it’s still a product of its time and therefore shows some of the unconscious attitudes of that time. It’s progress of a short that we notice it.

No Comments