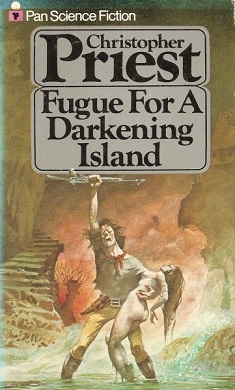

Fugue for a Darkening Island

Christopher Priest

125 pages

published in 1972

There are certain protocols you have to take into account as a reviewer when discussing the books of a new, young writer. Protocols that are still in effect when the author has aged more than forty years since the first publication of his novel and has become a grand old man in the meantime, prone to gently correcting younger writers. Anything that can be said about Fugue for a Darkening Island has to be tempered by the realisation that it is a fortytwo year old novel, not necessarily indicative of the writer Priest now is.

But the truth remains that Fugue for a Darkening Island is a problematic work, a novel with its heart I think in the right place, but which features certain unfortunate themes in Priest’s work that will return in later novels, somewhat muted. I’m thinking of last year’s The Adjacent, featuring a near future Islamic Republic of Great Britain as well as the much earlier A Dream of Wessex which had parts of Britain as a caliphate, but also of The Separation and its naive story of a better world created by a separate peace between nazi Germany and Britain. In short, Priest sometimes goes for settings you’d sooner expect to see in the stories of the more reactionary Baen writers and A Fugue for a Darkening Island is one of those novels, a near future Britain ripped straight from the front pages of National Front propaganda, as the country is flooded by a never ending stream of African refugees destroying the British way of life, its hero a decent middleclass Englishman trying to find a new home for him and his family.

If that sounds like the setup for a British version of The Turner Diaries, this wasn’t his attention according to Priest. In the introduction to the revised edition that came out a few years ago, he actually lamented the fact that what was received as a progressive story at the time of publication, became much less so over time. It is of course not alone in this; much of the earnest progressive commentary on the matters of race in the media of that time now comes across as borderline racist or worse today, if only because of a lack of input by those actually suffering from racism. Priest wanted to comment on the struggle with the birth of Britain’s multicultural society as well as the Troubles in Northern Ireland and the predicted “race wars” that were bound to happen in England through the usual science fictional exagerration. Which is what good science fiction writers should do, but when even the revised edition of your novel can still draw an admiring review from a rightwing xenophobic site, you do have to wonder if you’ve done the right thing. And for god’s sake don’t read the comments.

In Fugue for a Darkening Island a nuclear war has made much of Africa uninhabitable, leading to an exodus from the continent to better places, including Britain. The first most Brits notice of this is when bodies of refugees start wash up on their beaches (not unlike what’s been happening in the Mediterranean in real life currently). As the number of refugees increase and start to land in Britain, a rightwing government is elected to handle it; its autoritarian measures are useless though and as tensions increase, more and more white English take matters in own hand. Riots, street fights and racial conflicts lead to a general civil war as the country disintegrates and the central government disappears. All of which we see first hand through the eyes of Alan Whitman who is not the most sympathetic of narrators, a thoroughly middle class family man, regularly cheating on his wife.

The first words of his story are “I have white skin”, as he describes how he looks when the crisis first hit him and his family personally, then six months later, as the country has disintegrated. Throughout the novel we get these three distinct storylines, the first following Whitman in the present trying to survive in the aftermath of the civil war, the second telling how the refugee crisis went from background noise in his life to engulf him and the last telling the broader story of how the crisis came to be, following Whitman in his everyday life. It’s effectively done, the storylines echoing and re-echoing each other.

Whitman as said is not a sympathetic character and he comes over as flat and affectless, rarely emotional. This actually fits in well with the horrors he encounters. It also helps to counter some of the racist appeal of the scenario, avoiding lurid descriptions of racial violence. Nevertheless reading this some four decades later, the similarity with more noxious rightwing racial fantasies kept me uncomfortable throughout it.

Though this was mildly controversial when first published and made Priest known to a wider audience, Fugue for a Darkening Island is a minor work, something that points to his later, better work, but done much more clumsily and less subtle. Probably a novel you can safely skip unless you are a Priest completist.

No Comments