Who Fears Death

Nnedi Okorafor

386 pages

published in 2010

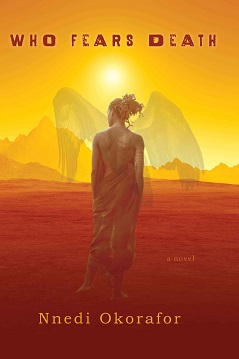

As I was reading Who Fears Death, about a third to halfway through it, a simple question sprung to mind: why did I think this was set in Africa? There had been no recognisable place names, no mention of Africa, no hint of what the Seven Rivers Kingdom corresponded to in the real world until almost at the end of the book, when it’s revealed to once have been part of the Kingdom of Sudan (which as far as I can determine, has never existed, at least not under that name). Yet from the start I had no doubt this was set in some part of Africa, but why? Was it just because Nnedi Okorafor is a Nigerian writer? Or the cover, which does look very “African”? Ironically, for once in a field where protagonists are often whitewashed on the cover, here the opposite may have happened; the heroine, Onyesonwu, is described as being “sand dune coloured” in the book, paler than most people.

Because of this, by just looking at her, people know she’s the child of rape, an Ewu, born of an Okeke mother raped by a Nuru man, as part of a strategic campaign of ethnic cleansing by the Nuru of the Okeke, traditionally their slaves. Any child born of rape is not just a permanent reminder of Nuru superiority, it also undermines the Okeke’ future directly, as they aren’t Okeke and nor would their children. Onyesonwu therefore, like all Ewu, is outcast, barely tolerated in Okeke society and that only because of her father, not the man who raped her mother, but the man she chose for her when she and her mother came out of the desert they’d been living in. And it is when her father dies when she’s sixteen, that everything changes for Onyesonwu, when it becomes public that part of the unwanted heritage she has gotten from her mother’s rapist is the ability to practise magic. Now she has to find somebody to teach her how to control her powers and how to use them to protect herself.

That’s all in the first two short chapters, setting up the rest of the story. At the end of the first chapter it’s established that it’s being told by Onyesonwu to an unknown listener, four years after the death of her father, while she’s waiting for her own death. Throughout the rest of the story she occassionally flashes forward to this moment, as we learn more about why she ended up there. At first the story is told mostly in flashback however as Onyesonwu talks about her growning up and trying to fit in with a society in which she’s an outcast. Her innate sorcerous abilities, in a society where of course sorcery is the domain of men, doesn’t help. Large parts of her story revolve around her struggle to control and learn to use her powers, in the face of the (well intentioned) refusal of those who could help her.

The town Onyesonwu lives in is far removed from the realities of the slow burning civil war that her mother fled, but as the novel progresses it comes closer. It also becomes that the driving force behind the genocide of the Okeke is her own father. And with Onyesonwu’s becoming a woman and growning mastery of her sorcery, she comes to his attention, seemingly setting things up for a familiar quest story, in which Onyesonwu has to defeat her father and overcome the racial and tribal perjudices of both her peoples.

Though this is what more or less happens, it doesn’t quite fit the mold though. Onyesonwu often is more pawn than hero and never escapes the fate that she sees in her initiation rite when the local sorceror master finally takes her as his pupil. At which point it also becomes clear to the reader, if it hadn’t already, that she’s narrating the story shortly before she will be killed by stoning. She’s at peace with this, as the same vision also revealed that her death would change everything for the Nuru, Okeke and Ewu.

But what really sets Onyesonwu apart from a Luke Skywalker say, is that once in full possession of her powers, she’s as destructive and vindictive as her father. When her friend is killed in one town, she blinds the inhabitants. Worse she inflicts on the Nuru capital, through killing every Nuru male in it, whil impregnating every Nuru female, avenging what was done to her mother a million fold.

This isn’t really the sort of behaviour we expect from our science fiction or fantasy heros. Sure, genocide is always the first option space opera protagonists reach for when things get difficult, but it’s supposed to be done rationally, not so emotionally as this. It also makes a mockery of the elegant structure of the prophecy she’s supposedly enacting, as her actions have already changed the world, her death just a coda.

And all through this I kept wondering why it felt so African to me when it was only on the very last page it was revealed it was indeed set in Sudan. Granted, the genocide and civil war reminded me of the South Sudan and Ruanda, but it could’ve just as well been Bosnia twenty years ago. Perhaps it was that curious mixture of what seemed like superstition mixed with actual sorcery embedded in a society that seemed organised on the village level, where high technology like computer tablets do exist, but seem external to village life. Maybe Who Fears Death is just deliberately designed to feed on our prejudices and stereotypes of “Africa”.

This wasn’t an easy novel to read, much more so than Lagoon was. I”m not sure it entirely succeeded in what it set out to to, or even what that was. If you’re new to Okorafor’s writing, perhaps Lagoon would be a better start.

No Comments