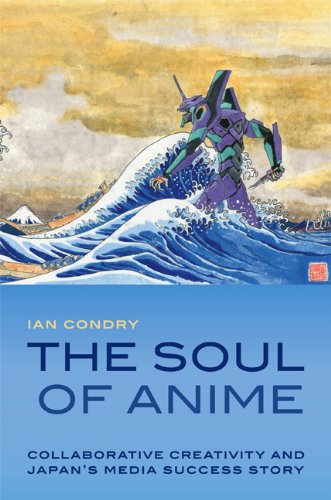

The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story

Ian Condry

242 pages including notes and index

published in 2013

Sometime in 2015 I became obsessed with anime. I’m not sure why, but from something that I had only a passing interest in, it became an overwhelming passion in the course of a few months. Before long just watching anime wasn’t enough and I wanted to know more about its history and the context in which anime was made. So I started reading blogs and anime websites and then looking for books. At the time a few books kept popping in any anime discussion that went further than whether Goko could beat up One Punch Man. Those included Sait Takami’s Beautiful Fighting Girl, Hiroki Azuma’s Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals and this, Ian Condry’s The Soul of Anime. I bought all of them, I tried to read all of them, but never managed to finish or understand any of them. I can only blame my own inexperience and lack of knowledge; I just didn’t know enough about anime back them to be able to understand them.

I was reminded of this book earlier this week by a tweet complaining about the lack of understanding of what anime is, which brought me to pick it up again. This time I managed to understand its purpose a lot better, now that I wasn’t labouring under the misunderstanding it was intended as any sort of history of anime. Instead what Condry was trying to accomplish should’ve been clear to me from the title. He was trying to pin down the essence of what makes anime anime, when it was no longer sufficient to say that anime is just Japanese animation. Much of the actual animation work after all is outsourced to other, cheaper countries, like Korea or the Philipines. At the same time, anime even at the time of writing was increasingly aimed at an international market, not necessarily the domestic Japanese markets. Similarly, the success of anime in e.g the United States also led to various local anime-like projects, like Avatar: the Last Airbender. Yet anime is clearly is its own thing, so how do we find out what that particular thing is made of?

Condry tries to answer this question through making use of techniques developed in ethnography. Specifically, he does so by interviewing and especially observing the people working on creating anime. For Condry, what makes anime interesting is the way it is being made. And he means that in the broadest possible sense of the word. The Soul of Anime looks not just at how various studios work, but also at e.g. the fansubbing community. As Condry explains in the first chapter, the book is the result of half a decade of field work done between 2004-2010 at various anime companies: mainly Gonzo, Aniplex and Madhouse, supplemented by visits to other companies in both Japan and the US as well as explorations into various fan activities. Condry also looks into the history of anime, though it’s fairly superficial, to further support his thesis.

For Condry, the “Soul of Anime” is its social aspect. Anime as a collaborative enterprise, networks of people interacting with their own ideas about anime, where the distinction between professionals, producers and fans, consumers is not that clear. It’s that collaborative creativity that links fan labour and professional labour for Condry, that made anime into the worldwide media success it is now. So for example you had the top down push of Nintendo’s global marketing campaign and the pull of overseas fans wanting to see the anime version of their favourite game that made Pokemon a global powerhouse. It is a decent enough explanation for what makes anime and the anime media complex different from other media, but I’m not quite convinced that this really is all this unique to anime, especially now.

There is no getting around it: The Soul of Anime is dated, in some aspects badly dated. The book was published in 2013, which already makes it ten years old, but worse, most of the field work Condry did was done in 2005-2006. A lot of his references therefore are almost two decades old at this point and take place in a very different world. There’s no mention of streaming in here. Crunchyroll was founded in 2006 but was still a piracy site at the time. Overseas fans still had to get their anime either from tv broadcasts or through licensed DVDs. Anime was popular outside Japan, but still very much a cult phenomenon mostly. Espcially in the fansubbing section of the book, things have changed so much that it has become mostly useless for understanding modern anime culture.

Reading The Soul of Anime is like opening a time capsule of what anime was like in 2006, on the cusp of global success and mainstream acceptance, but hesitant about what that would mean. Which means that Condry spends time examining the Gonzo series Red Garden as an example of an internationally orientated anime series because it’s set in New York. In a world in which Netflix and Disney order their own anime series this is small beer indeed. In 2023, with anime being a globally consumed medium and streaming media in general being much more globally orientated; Netflix streaming Korean game shows and cute romcoms alongside Mexican and Spanish mafia dramas, some of its uniqueness has been lost. This is also true in fandom, with fandoms for mainstream ‘properties’ evolving to be more like anime fandoms.

I’m not sure whether this undercuts Condry’s thesis, but it is something to take into account when reading The Soul of Anime. In the end it is a very mid-2000s look at what anime is, with very mid-2000s idea of what anime fandom and otakus are like. I’m not sure it really fits modern anime fandom anymore. Nevertheless a good, accessible book to get into anime criticism with.

No Comments