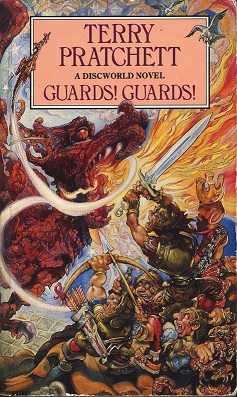

Guards! Guards!

Terry Pratchett

317 pages

published in 1989

For me Guards! Guards! is the last novel you can describe as an early Discworld novel. From here on all the major subseries have appeared: Rincewind, Death, the Witches and now the Night Watch/Sam Vimes novels. It’s the first novel in which Ankh-Morpork becomes more than generic, somewhat over the top fantasy city, with the first extended cameo for the Patrician and the first insights in how he rules the city. Over time Ankh-Morpork and the Night Watch would come to dominate the Discworld series of course; every novel in the main series since The Fifth Elephant either set in Ankh-Morpolk or featuring the Watch or both, but of course we didn’t know that at the time. Back then it was just Pratchett taking the mickey out of yet another set of fantasy cliches.

In Guards! Guards!‘s case, he did that by importing another set of cliches, that of the hardboiled police procedural. Sam Vimes is a hero straight out of an Ian Rankin novel: the grizzled, older, cynical detective staying in the Night Watch because he has no other place to go. He remained in his post even as the watch has degenerated into a farce and he has become a captain of only three men: Fred Colon, a fat sergeant, Nobby Nobbs, a weassely corporal and a new dwarf recruit called Carrot Ironfoundersson.

Well, I say dwarf recruit, but turns out, to his own shock, that Carrot was adopted, which might be why he’s over six feet tall; somewhat on the big side for a dwarf. Culturally though, if not physically Carrot is dwarvish to the core: honest, loyal, law abiding and extremely literal. He’s actually naive enough to want to enforce the law, which awakes something in Vimes he thought was long dead.

Meanwhile there’s a conspiracy afoot. This is not new; conspiracies are always afoot in Ankh-Morpork, whether occult or otherwise, but this is a different kind of conspiracy. It’s a conspiracy of the petty, the spiteful, the narrow minded little people unsatisfied with their lot in life, jealous of others. Their plan is simple: summon a dragon to threaten the city, so that the true king of Ankh-Morpork may return and chase the patrician, Havelock Vetinari, from his throne.

The Night Watch is of course caught in the middle and are in fact the first to run into the dragon. Investigating its appearance Sam Vimes makes the acquaintance of Sybil Ramkin, dragon breeder and high nob. The meeting between the two is not so much love as mutual fascination at first sight. Vimes quickly realises what a powerful ally she is.

What’s interesting about Guards! Guards! is the number of strong characters in it. Not just Sam Vimes, but Sybil, the Patrician and corporal Carrot are all very strong in their own way. Carrot’s strenght is the simplest, a good humoured force of nature, while Vetinari and Vimes both are much more devious and cynical, with the former more willing to accept the consequences of his cynicism, while the latter has an inner core of decentness that is its own strength. Sybil finally has that jolly hockeystick strength of the old (English) aristocracy, that ability to keep a cool head in a crisis.

There’s more of Pratchett’s evolving humanitarianism on display here as well, which would become a persistent theme with the Vimes novels. It’s not so much here that Pratchett objects to autocratic rulers — Vetinari certainly isn’t a democrat — as that he objects to unthinking veneration and rulers who just want to rule with no thought to the country they rule. Vetinari is intensly concerned about Ankh-Morpork, while the shadowy master behind the conspiracy is willing to let it be destroyed if it means power. It’s something we saw in Wyrd Sisters as well.

It’s of course an inherently conservative worldview, though it has its attractions to more liberal minded people as well, that idea of the benevolent, enlightened despot. This is what, more so than the presences of trolls and dwarves and dragons that makes the Discworld a fantasy novel, this idea that this could work.