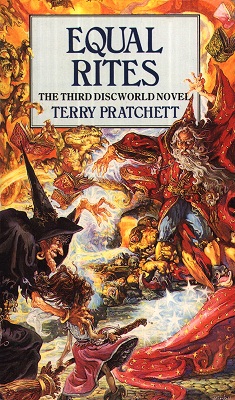

Equal Rites

Terry Pratchett

283 pages

published in 1987

With the third novel in the series, Equal Rites, it became clear that the Discworld was more than just the sum of its characters. Gone were Rincewind, Twoflower and the Luggage, as an entire new setting and cast turned up. This wasn’t something that had been done much — or ever — in fantasy before, not often done after either. It must’ve seemed a bit of a gamble at the time, but this freedom to change protagonists and settings is what made the Discworld series, what has been keeping it from going stale for so long. If you don’t like one particular subseries, there are several others that you can read. Of course it also helps that Pratchett has been such a good writer for so long…

Equal Rites is the first Witches story, though the Granny Weatherwax that shows up here isn’t quite the one we get to know better in the later novels, differing somewhat even from how she’s portrayed in Wyrd Sisters three books onwards. The plot of the story is all about how if you’re a wizard on the verge of dying and looking for an eight son of an eight son to hand your staff over to, it helps to not be too hasty and check that eight son of an eight son isn’t actually a daughter…

Which it turns out to be and Eskarina “Esk” Smith duly turns out to have wizardly powers. Unfortunately, girls can’t be wizards and besides, in Bad Ass there’s nobody to teach her wizardry anyway. Instead, once her talents become too much to be ignored, she’s apprenticed to Granny Weatherwax to become a witch. Witchcraft is very different from wizardry though, much more headology and herb knowledge, less turning people into frogs or spewing flames from a staff.

It turns out to not be enough for Esk, she needs to learn proper magic and runs away to Ankh Morpork, followed by Granny Weatherwax. On the way she meets an apprentice wizard named Simon, one of the greatest magical talents the Unseen University has seen in eons. He’s very good in theoretical magic, where he can explain things so well that he can make his audiences become ignorant on a much more fundamental level than ordinary people. Simon, while brilliant and a decent bloke all around is unfortunately somewhat of a beacon for the things from the Dungeon Dimensions, always looking for a way into the Discworld, which is the dimensional equivalent to close to the shops and near the buses. Of course it’s up to Esk to save him, but she has her own problems as well, starting with the struggle to be actually taken seriously by the wizards of the Unseen University.

Equal Rites is beside the first witches book, also the first Discworld novel in which we get a closer look at non-Rincewind wizards, who don’t come out looking all that well. Chauvenistic, overtly proud, constantly scheming amongst each other to advance their careers (usually by making sure the wizard standing in their way is no longer doing so for reason of death), they’re still a while away from their later portrayals. Wizardry is also somewhat more dangerous than it would be later, with the wizardy death toll not insignificant here and in the next two books…

Though Pratchett is firmly on Esk’s side regarding her ambitions, he’s still fundamentally conservative here: the status quo of female witches and male wizards is quickly reinstated, Esk and Simon get their happy ending and exit stage left and nothing more is heard of female wizards for the rest of the series. There is somewhat of an separate but equal vibe to this whole wizards and witches setup, certainly in these early stages.

On the whole Equal Rites is a giant step forward in Pratchett’s evolution as a writer; it feels much more like a proper Discworld novel than the first two books did.