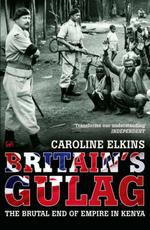

Britain’s Gulag – The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya

Caroline Elkins

475 pages including index

published in 2005

Before Tom Wolfe used “Mau Mauing” to describe the ways in which well meaning, white government officials where cheated out of welfare money through racial intimidation, Mau Mau was synonymous with a much greater terror. Mau Mau was the stuff of white colonialist nightmares: a freakish native cult of criminals and gangsters that savagely attacked innocent white settlers in their very homes, killing them and their families, mutilating their bodies. Sure, these people said they were freedom fighters, but you couldn’t take this claim seriously. Everybody who mattered knew Kenya wasn’t ripe at all for independence, that only the poison the Mau Mau spread through their pagan rites would cause the natives to question the benevolence of the British civilising mission in the country. Britain was therefore justified to use harsh measures to suppress this savagery and fortunately managed to do so, protecting the white settlers and loyal natives and crush the rebels, though it took them eight years, from 1952 to 1960 to do so.

That’s the myth of Mau Mau. The reality as Caroline Ekins describes in Britain’s Gulag – The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya is far different. There were incidents of Mau Mau savagery, but the British and settler response to it was much greater and was systematic, not incidental. It was under the Kikuyu of central Kenya, the most populous of the ethnic groups in Kenya and the group with the greatest grievances against British rule, as much of their land had been appropriated for white settlers that the Mau Mau rebellion was the most widespread, therefore the British did to the Kikuyu roughly what the Germans did to the Polish during World War II. The nazi plan for Poland had been to destroy its population as a people by murdering its intellectual elite, remove it from all the best parts of the country and herd the rest into the wastelands to serve as uneducated slave labour, with any resistance brutally put down. What the British did to the Kikuyu in Kenya was not quite as bad, but it came awfully close. It was motivated by security concerns rather than deliberate planning, but the endresult was still that less than fifteen years after World War II the British in Kenya had recreated much of the nazi system in dealing with the Kikuyu’s struggle for freedom.