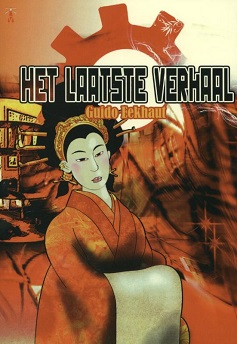

Het Laatste Verhaal

Guido Eekhaut

332 pages

published in 2011

The problem with doing review projects, like getting myself back to speed with Dutch language science fiction and fantasy, is that it can lead you to read and finish books you’d normally put aside long before. Such is the case with Het Laatste Verhaal (The Last Story) which I thought was going to be some sort of cyberpunk story but turned out quite different. It also didn’t help that this turned out to be part of a loose series, something I only noticed once I started reading the novel.

Basically Het Laatste Verhaal is set in a world which had what’s assumed to be an alien visitation in the 1800s and those Bezoekers (Visitors) have been shaping human history ever since. Tall, pale and white haired the Visitors resemble nothing so much as vampires, but nobody calls them that to their face. In the near future Flemish Republic of 2019, they hold most of the power behind the screens, with democracy just a sham to placate those few still bothered by politics among the citizens, while the once strong unions also lead a kabuki existence, there because the all powerful companies sometimes need a trustworthy advisary. For those unable or unwilling to keep citizen status, there are the streets. Matthias is one of those, fled the safety and comfort of his father’s house to live a precarious existence outside the system.

Meanwhile, sometime in the future the entire world is ruled by what seems to be a new Japanese Empire, one that for all the splendour and decadence at court is destroying itself from the inside. Lady Kiyo, Imperial Storyteller was once part of a failed rebellion and now has infiltrated the court in an assassination attempt. At least that’s what her co-conspirators think, but she just wants to tell the emperor the real truth about his empire.

There’s another secret Kiyo’s hiding. During one of the last battles of the failed revolt against the empire, a Visitor was killed and Kiyo stole the sword he was carrying. This is a sword that can cut anything, doesn’t just slide through steel if it wasn’t there, but is so sharp it can cut holes between worlds.

Which is how Kiyo finds herself in Matthias’ Flanders, just in time to save him and his friend from a beatdown by a skinhead gang. It turns out quickly that her version of history and his don’t match up, but they don’t have much time to wonder about it, as the skinhead gang is still after them and worse, so are the Visitors, wanting their sword back…

Meanwhile there are a couple of other storythreads, one about one of the up and coming managers of one of the vistor owned companies plotting his way to the top, the other about probably the last union leader in Flanders still driven by ideology and concern for the workers, rather than his own career. These sort of weave in and out of the main plot, without contributing much to the story.

In general this is a very male book, with only two significant female characters, one of whom dies quickly to show the seriousness of the skinhead threat. Lady Kiyo is interesting, a peasant girl turned revolution leader turned storyteller, but Matthias is a bit dull, as is the neoliberal Republic of Flanders, which makes little sense especially since it’s set in 2019, too soon for all those changes, though there are hints that this too is an alternate history.

Guido Eekhaut certainly isn’t a bad writer, on a nuts and bolts level, but this novel was a disappointment nonetheless: confusing, meandering and without a real ending. It felt like the middle volume of an unfinished trilogy. A pity.