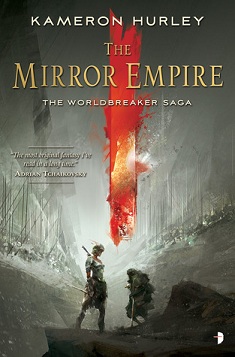

The Mirror Empire

Kameron Hurley

540 pages

published in 2014

Kameron Hurley’s debut novel Gods War had an impact many other writers would envy her for, only equalled by the buzz generated by Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice last year. It wasn’t just an accomplished debut novel, it also helped revitalise science fiction at a time when it started to grow a bit stale again. Expectations are therefore high for Hurley’s new novel, The Mirror Empire, the first in a new series and the first fantasy novel she has published. Would it be as good and inventive as her previous series, would she be as good at writing fantasy as science fiction?

Halfway through Mirror Empire I finally realised what it reminded me off: Steven Erikson’s Malazan series. Not so much in setting or plot, but rather in complexity and willingness of both authors to throw all sorts of interesting ideas into their novels, ideas you may not expect in what at first glance seems to be a standard epic fantasy series. Where they differ is that Hurley is much better at inclueing the reader about who all these people are and how everything fits together, where Erikson had a magnificent disdain for the reading, leaving them to sink or swim on their own. Hurley is … more forgiving but still requires you to pay attention. This is not a novel to read with your brain in standby.

Luckily Hurley has provided a cheat sheet, in the form of her promotional blog tour she undertook for The Mirror Empire. As you may know, her first publisher went into a spot of trouble that almost sunk her writing career until she got taken on by Angry Robot. Though I do have the feeling she severily underestimated how well know and popular she actually is, I can’t fault her for deciding that she needed to pull out all the stops to promote what might be her last chance at kickstarting her writing career. Hence the blog tour in which she talks about The Mirror Empire, why she wrote it as she did and the choices she made. If you haven’t read the novel you may therefore want be careful with reading those posts, because they do reveal a lot about the story, but it’s a boon to refresh your memory afterwards.

I started The Mirror Empire last Sunday when I read a large chunk sitting in my garden, then basically read it in fifteen-tweny minutes chunks on my commute, finishing it today, on Thursday. It read incredibly fast, pages flew by, chapters were read in minutes. Normally that’s the sign of a shallow book, something you don’t need to pay too much attention to read, but that’s not true here. Because I also found that I needed the time between commutes to think about the story, while going about my day, letting it bubble in my subconscious. As Hurley’s blog tour shows, there was a lot of thought put into this novel and I needed the time to process that.

The worldbuilding I especially was impressed with. The Mirror Empire takes amongst three different societies: the Dhai, Dorinah and the Saiduan, on one continent of one world. The latter two seem variations of well known pseudo feudal, medievaloid fantasy societies, but the Dhai are something else: vegetarian pacifist cannibals living in the middle of a wilderness filled with ambulatory predatory trees and other dangers. Their towns and temples are protected by various barriers as well as the talents of their priests or jistas, those who can draw on the powers of the various satellites that circle the world. As these, in their complicated years and decades long orbits draw closer or further, their powers become greater or lesser. The most elusive of the satellites is Oma, not seen for 2,000 years but whose rise always is accompanied by great and violent change. No points for guessing which satellite is starting to rise at the start of the novel.

But we don’t know that at the start of the novel, which begins with the main protagonist, Lila, losing her mother in a raid by a warband of Dhai. She escapes only because her mother, a bloodwitch able to work magic through the use of, well, blood, throws her through a gate to another world, where Lila is raised as a temple drudge for the Temple of Oma. Meanwhile in Saiduan the country is under attack from a relentless horde of invaders, invaders who seem to step out of tears in the sky, while in Dorinah the empress there entrusts her captain general with an important task: to ethnically cleanse all the Dhai slaves in the empire. All pieces of the same puzzle and to the reader it becomes relatively quick clear that’s what’s happening is no less than an invasion of a dying parallel world, where the Dhai are not cuddly pacifist cannibals, but aggressive conquerors who’ve taken over most of their world and now want to do the same to this world.

None of the characters in The Mirror Empire fit the traditional heroic mold. Lila is disabled with bad leg and asthma, while e.g. the Dorinah captain general, Zezili Hasaria, is more than happy to follow her empress’ orders for genocide, until driven by necessity to go against them. The closest the book comes to a true heroically good character is Ahkio, the kai or leader of the Dhai who tries to keep to the traditional virtues of his people even in the face of this existential crisis.

Which brings me back to the Dhai society, which not only distinguishes some five different genders (as well as people who don’t fit any of them) but which is also egalitarian and based on a radical form of consent, where even a simple touch on the arm needs to be consented to. This is something that’s genuinely new to me; I don’t think I’ve seen this before in either fantasy or science fiction.

In general, as the blog tour shows, Hurley has put an incredible amount of thought in gender and gender relations and how to create societies that aren’t the tired old medievaloid creatures of lesser novels. There are the five genders, female passive, female assertive, male passive, male assertive, and ungendered which do not map entirely on our own notions of gender, as they’re built around specific roles these genders play in Dhai society as well as temperament and are fluid as people change over time and change their identity. Ahkio for example identifies as male passive, more conservative, more traditional and reserved, whereas if he’d identified as male assertive he’d been more individualistic and liberal.

The Saiduan too have a flexible gender system, acknowledging a third gender, the ataisa, inbetween male and female, but whereas with the Dhai gender is self identified, in Saiduan it’s enforced much more by society. That’s one of the ways in which Hurley is great at worldbuilding, by creating those subtle but fitting distinctions between societies while still seeing the similarities. What’s also interesting is that describing these gender systems and societies Hurley has created puts them much more in the foreground than they are when reading the novel. Most of the time you accept them like you’d accept the details of any fantasy world, as you accept that the people here ride dogs or bears, rather than horses.

There is one place though where these gender concerns are foregrounded, mainly in the subplot surrounding Anavha, husband to Zezili, the Dorinah captain general. Dorinah society is a matriarchal one where men fill the same role as women historically in our world, appandages of their wives, with nothing more to do than to look pretty for them and be there to fullfill their sexual needs and give them children. His chapters are in your face and uncomfortable and hard to read: it’s not that often you have this role reversal in a fantasy novel and have it shown up so starkly. His story is what’s going to stick in some people’s craws, if anything is.

For me personally though, I’ve only scratched the surface of what makes The Mirror Empire great and I can’t wait for the sequel. Already this is a worthy candidate for the Hugo and Nebula Awards and certainly a much better novel than Gods War.