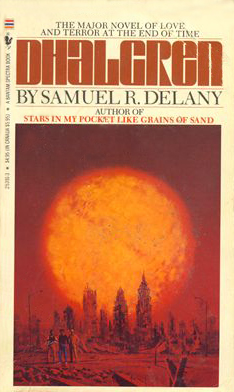

Dhalgren

Samuel R. Delany

879 pages

published in 1975

Question: what are the two places man will never reach? Answer: the heart of the sun and page 100 of Dhalgren.

A corny old joke, with a kernel of truth because Dhalgren is not an easy book to read. Almost 900 pages long it’s a monster of a book, even more so when you remember it was published at a time when any science fiction novels over 200 pages was a bit on the long side. And unlike certain modern novels of that length, Dhalgren demands your attention on every page; you can’t get through it on the autopilot. It’s therefore no wonder that it took me most of February to read it, with no time for other books. But it was worth it as even almost forty years later this still is one of the most ambitious and challenging science fiction novels ever written.

Some people think it’s the symbol of everything that went wrong with science fiction. That “joke” I opened is less a joke than a sneer, repeated by people still mad at what the New Wave did to science fiction though they were born long after it. According to them Dhalgren is dense, impenetrable and unreadable, elitist fodder for literary snobs. What really sticks in their craw though is that Dhalgren was one of the biggest science fiction bestsellers of the seventies, going through fifteen printings between 1975 and 1980. Somebody must’ve liked it; in fact, like Dune or Stranger in A Strange Land, much more palatable bestsellers to these embittered fans, it must’ve appealed to people outside science fiction’s core readership.

In fact, what made me read Dhalgren, after I’d tried it years ago and failed less than twenty pages in, was reading how it was actually an entry point into science fiction for at least one reader:

i don’t know why everyone considers Dhalgren a bad place to start, it is what convinced me to love SF, because it was about cities, and queerness, and how language worked, and about the potential of otherness…and so much of the SF i read, even the work about cities was so tight and ironically contained.

That convinced me I should try and give it another go. Delany was already one of my favourite writers, but for the most part I’ve stuck to his earlier, more accessible or at least more mainstream, more explicitly science fictional novels. Dhalgren scared me, if only because with its length it would take a large investment in reading time to finish it. Indeed it took me the best part of February to get through it.

It was worth it though.

At its simplest, Dhalgren is the story of a man suffering from amnesia coming to a city suffering from an undefined apocalypse, having some adventures in it, then leaving again. The city is Bellona, cut off and forgotten in the rest of America, abandoned by most of its inhabitants, all law and morality and society broken down, the city in fact seemingly rearranging itself from time to time. The man, charismatic and easy going, coming into Bellona nameless but quickly nicknamed the Kid, Kidd or kid, taken into the various people and groups making a home in the post-apocalyptical city, enjoying the freedoms of it.

Kid is no leader, not interested or even thinking about rebuilding the city or even surviving; this is no post-apocalyptical survival fantasy or cozy catastrophe. He’s almost completely passive, willing to go along with other people’s plans and ideas. In the chapter before he comes to the city he meets up and fucks a strange woman; the first thing he does when comes to the city is to sleep with a strange man, just met. Significant that in a book filled with people who’ve taken new names for themselves, he’s the only one who was named by others and as a consequence, the only one whose name is in constant flux.

The city doesn’t have water, gas or electricity but nevertheless feels like a hippie wonderland, with one group living in a sort of earnest commune in the city’s park, another, the Scorpions, being the equivalent of a bikers gang. The Scorpions use an advanced holographic device to create signature holograms which envelop them and transform them into magical creatures. The closest we come to the tired tropes of post-holocaust fiction is when Kid one day takes the bus towards downtown and ends up at a department store controlled by a gang of middle class people who take potshots at anybody coming close. There are of course also those people who are still pretending to pretend that everything is normal, isolated in apartment buildings at the edge of town, reminding me a bit of that French-Vietnamese family in Apocalypse Now and how that clung to its habits.

Dhalgren has no plot, perhaps not even a story, but rather a series of events and vignettes Kids drifts in and out of, as the narrative is changed alongside his wanderings. Things move, events shift and time is unreliable. It’s mostly the Kid who notices this, but at several points it’s clear to everybody in the city, as another Moon rises in the sky, or the Sun comes up, huge and terrifying as if in the last of days.

Kid himself is perhaps the most typical of all of Delany’s protagonists: virile, rugged, not afraid of being dirty, with dirtied hands and bitten off, chewed up fingernails, wearing only one shoe, going barefoot on the other, armed with a bladed orchid worn at the wrist, blades sweeping out over the hand. Not necessarily homosexual but not afraid of sleeping with men, artistic but without artistic pretention, working class and autodidactic. He’s white but comfortable with blacks, accepting and accepted by them. Race, as befitting a 1975 science fiction novel, being one of the undercurrents in Dhalgren and even in the apocalypse there are racial differences. Bellona wasn’t a black city before, but is now.

Gender gets less of a look in. Delany has always been a very male writer I’ve found, not bad with or hostile to female characters, but much more interested in men. Here, there is some mention of contemporary gender concerns as there is of racial concerns, but it’s far less present. Race flows as an undercurrent throughout Dhalgren; gender only pops up on a few occasions.

This is a novel that makes sense only from scene to scene, where events follow each other in an apparant orderly fashion only to fade away leaving seemingly little impression. Things repeat, Kid finds a notebook in the park that contains some of the text we’re reading, starts writing in it himself, later is unable to tell which is his and which was already there. In the hands of a lesser writer this would all be irrating, boring and confusing, but Delany keeps your attention, keeps your interest, because you have to work to understand what he is doing while keeping you entertained doing so. But it is hard work and I can understand those who’d have to give up halfway through.