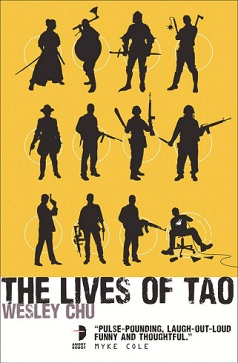

The Lives of Tao

Wesley Chu

393 pages

published in 2013

I read this because Wesley Chu was nominated for the 2014 John W. Campbell Award for best new writer and it was available in the Hugos Voters Package. I’d also seen it recommended at the local science fiction bookstore and had picked it up once or twice to sample it, though was never convinced enough to buy it. Because I was visiting my hometown for a couple of birthdays this weekend I took the opportunity of two long train journeys to read this, which worked out well.

From Myke Cole’s cover blurb — pulse-pounding, laughout-loud funny and thoughtful — you might guess that this was meant to be an action comedy story, which it was, but without the humour. This just wasn’t funny, I’m not sure it was actually ever meant to be funny and if you read this, set your expectations accordingly. The Lives of Tao actually is a geek wish fulfilment sf thriller, where the fat, underachieving, nerdy slop is taken out of his comfort zone and thrust into a worldwide conspiracy and finally gets the girl he’s been silently lusting after but was afraid to ask out. There may be a bit of pandering in this, you may have guessed.

The fat slob is Roen Tan and the way he’s trust from being just an office peon into the heart of a millions years old war between two alien factions covertly struggling to guide human history, is because one of those aliens had its host body die on it and Roen was the only one available to take him on. The alien is Tao, his previous host body was a suave James Bondesque secret agent with decades of experience and now Tao has to not only learn to work together with somebody new, but that somebody is as far from secret agent material as well, me.

The war Roen has been drafted into is between two factions of the same alien race, who crashlanded on Earth millions of years ago (and might have caused the extinction of the dinosaurs). They’re semi-corporeal, only able to survive on Earth long term by bonding with an animal. Millions of years pass, humans sort of start to get things going and the aliens start to guide human evolution with the sole goal of getting technology up to the level that they can go home. Along the way these aliens split into two factions: the Genjix, who are completely ruthless in chasing this goal and the Prophus splinter group, who are a bit more mellow and human friendly, who’ve been waging a covert war, manipulating history for centuries.

A lot of this book is setup material for what will be the rest of the series, as Roen is trained for his new role as one of the agents fighting this covert war and to help him with this he gets his own personal trainer, Sonya, who is basically the walking embodiment of the sexy, smart tough, uber capable female secret agent, there to both help the hero on his way and to serve as a trophy for his success. Chu sort of avoids some of the more skeevy aspects of this cliche; Roen falls for her and she for him as well, but they don’t get together and they become friends instead of lovers. It’s still such a cliche though and the way Sonya is consisently described, male gaze and all, is problematic too.

Much of the plot revolves around getting Roen into shape, while the Genjix are hunting for him and Tao and the latter slowly reveals to Roen his history. This is done in short paragraphs at the start of each chapter, much of which is set in the East and reveals that Tao had “possessed” e.g. Genghis Khan. As such The Lives of Tao is a typical setup book for the rest of the series, the second book of which has already been published. If you’ve read your share of thrillers and sf adventure stories, much of the shape of the story will be familiar to you, with the climax of the story being a series of set pieces.

The central idea driving the story isn’t that original either of course; giant conspiracies secretly manipulating history and historical figures being secret aliens are a dime a dozen in technothriller land. The way Chu has portrayed it here it seems all of history and anybody of historical importance was an alien, which is just one of those things you have to swallow for the sake of the story; a cool idea but which falls apart when you examine it closely. A lot of The Lives of Tao feels that way to be honest, e.g. if Roen/Tao is feared so much the Genjix pull out all stops to find him, why is he able to stay in his flat?

The Lives of Tao is not a bad book, certainly not for a first novel. It moves along quickly and Chu has a good eye for writing fight scenes, which help a lot in an adventure story like this. What lets it down are the sexual politics, especially in the climax of the story where the oh so capable Sonya becomes just another damsel in distress as well as some of the sloppy worldbuilding. As long as you’re not too annoyed by the first and can read fast enough not to stumble over the latter, this is a decent enough romp.