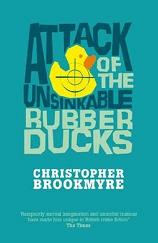

Attack of the Unsinkable Rubber Ducks

Christopher Brookmyre

343 pages

published in 2007

Picture Richard Dawkins with all his disdain for religion and new agery intact but a better sense of umour and a career as a thriller writer rather than a scientist and you have Christopher Brookmyre. Especially in his Jack Parlabane series, of which Attack of the Unsinkable Rubber Ducks is the latest installment, religion and quackery are what motivates the villains with the hero being a rational atheist who makes sport from revealing the hypocrisy of religious authorities. At times this relentless hostility, no matter how well deserved does get a bit tedious even for me. If you’re at all religious, Brookmyre is probably not your cup of tea.

With Attack of the Unsinkable Rubber Ducks Brookmyre shifts his focus slightly, from organised religion to quackery: spiritualism to be precise. Yes, it’s Jack Parlabane versus those parasites on human misery, the douchebags who pretend to be able to contact the dead when all they have is a lack o shame and a talent for cold reading. Jack knows it’s all nonsense, the dead are dead and there’s no such thing as ghost but there’s one niggling little detail: Jack has become a ghost himself. He’s dead, fallen out of a four storey window and landed on his headm but he’s still here narrating. How is that’s possible? He doens’t know but he knows he doesn’t like it and certainly grudges having to admit that the Woo peddlers might just be right…