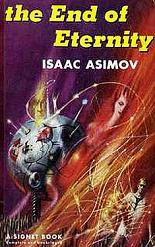

The End of Eternity

Isaac Asimov

192 pages

published in 1955

So it turns out that in the more than seven years now that I’ve kept this booklog, I had not read any Asimov novel at all. Which is somewhat strange, as it was for a large part due to discovering Asimov in my local library’s youth section that I became a science fiction fan. I, Robot for example may very well have been the first proper science fiction book I ever read. For a long time Asimov was

in fact the gold standard against which I measured every new science fiction writer I came across. If they weren’t at least half as entertaining or interesting I wouldn’t bother with them. Of his many novels and stories it was this, The End of Eternity that was my favourite, one of the first science fiction books I bought for myself and the first to introduce me to the idea of time travel as more than an excuse to visit scenic parts of the past. Rereading it, the question was whether it would be as good as I remembered it to be. So many novels first read as a child disappoint when you reread them; fortunately this didn’t. In fact, it read almost exactly as I expected it to be.

The central idea in The End of Eternity is the existence of Eternity, an organisation that monitors and safeguards all of humanity’s history from the first invention of the secret of time travel. Most people outside of Eternity think the organisation only exists to facilitate trade between various centuries and perhaps in some vague way protect them from the unspecified dangers of time travel. What they don’t realise is that Eternity in fact exists outside of time, from which realm it can not just study and monitor time, but alter reality to make sure that humanity is kept on an ever increasing path to perfection. A whole organisation of Computers, the people who calculate these reality changes, Technicians, who execute them and various other specialists all work together to this goal, over a span of time that is literally millions of years long. Power is provided by tapping into Nova Sol, the Sun as it goes nova at the end of its lifecycle. An incredibly neat idea, not quite original to Asimov, but as I said the first time I encountered it was here.