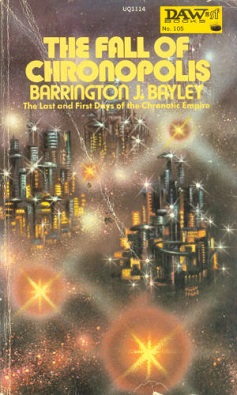

The Fall of Chronopolis

Barrington J. Bayley

175 pages

published in 1974

I’ve always been a sucker for time war novels, starting with Isaac Asimov’s The End of Eternity, Fritz Leiber’s The Big Time and Keith Laumer’s Imperium series. I like the grand scale on which these stories play out, the whole idea of the impermanence of time itself, something that undercuts our most basic of securities, the idea that the past we remember is the way that past has always been, making literal the idea Orwell put forth in 1984: he who controls the past, controls the future. Which explains why The Fall of Chronopolis was one of the first bought at Eastercon novels I finished, even before the convention itself was over, finishing it at the Dead Dog party on Monday.

In the The Fall of Chronopolis the time war rages between the Chronotic Empire, which has steadily increased its dominion over the centuries until it rule a thousand years of human history and its far future enemy, the Hegemony, existing futurewards beyond the Age of Desolation after the fall of the Chronotic Empire. For the most part this time war has been limited, consisting of limited raids on each other’s history, but the Chronotic Empire is raising a grand fleet of timeships to invade the Hegemony directly, while the latter had developed a time distorter which can warp history directly. But this is only the surface story; there’s a lot more going on

Bayley’s conception of time travel consists of a “temporal substratum” or strat that the time ships fly through, which would make any time traveller insane if they looked at it directly. The strat exists “below” orthogonal time, in which history is made, remade and unmade, entiry cites be cast into nonactual, merely potential time. Only within the strat can alterations of history be seen and remembered, at least for a time. From within the strat the warring parties could fight in a duel of moves and countermoves aimned at altering their opponent’s history to such an extent their time ships no longer had an orthogonal base of existence; they could still exist in the strat, for a while, until they faded out, sinking into what the Church calls the Gulf of Lost Souls.

What’s more, time is divided in nodes, as explained in a very traditional “as you know, Bob” classroom lecture at the start of the second chapter, nodes each roughly 150 years apart, as orthogonal time has a wave structure. Time travel is easiest from node to node, as it doesn’t cost a time traveller energy to remain in a node. Travel to points of time inbetween nodes does and the traveller needs to keep spending energy to keep in phase, or sink back into the substratum. This gives the empire its structure and stability, having expanded over seven such nodes.

Captain Aton commands one of the time destroyers in the empire’s fleet and during one battle with the Hegemony he falls foul of a sect of Traumatics, heretics split off from the true church and worshipping what they believe is the master of strat time, Hulmu. In a seperate plot line, a woman, Inpriss Sorce, is chosen at random by the same Traumatics sect to serve as a sacrifice for their service, but first they’ll get her to flee across the entire Chronatic Empire, to make the offer sweeter. Her and Aton’s paths will cross but seem to have no connection, until the very end.

Ultimately Bayley knots all these plots and subplots into one grand finale, in which in the grand tradition of time war stories, time is revealed as an eternal loop, already foreshadowed in the belief of the emperor as the soul as eternal in time, caught in a loop along its own time line.

A lot happens in 175 pages, helped a lot by the breezy, pulpy style Bayley tells his story, very old fashioned for a novel originally published in 1974. This must’ve been a deliberate choice to tell the story this way. Bayley after all was one of the New Worlds school of New Wave writers, people who took apart and reassembled traditional science fiction, injecting literary techniques from other genres in it. The time war subgenre is quintessential pulp science fiction, but also a genre that has lend itself well to experimention. I still maintain Asimov’s entry was the best novel he’d ever written, while Leiber’s was an exercise at greating the grandest possible canvas in the smallest possible setting. Bayley’s story fits in well with this tradition.