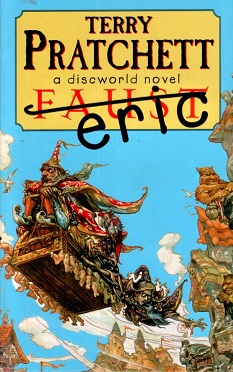

Faust Eric

Terry Pratchett

155 pages

published in 1990

Eric is a bit of an odd duck in the Discworld, out of place amongst the increasing sophistication of the last couple of novels coming before it, almost a throwback to the very first few books. It’s a lot shorter, a lot less serious and a lot more written for comedic effect than its immediate predecessors were. All of which can be explained by the simple fact that it was first published as an illustrated book, written around a series of Josh Kirby illustrations, which was later adapted into standard Discworld paperback format, losing most of its charm in the process.

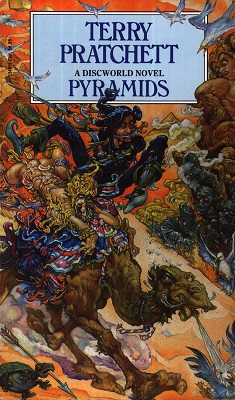

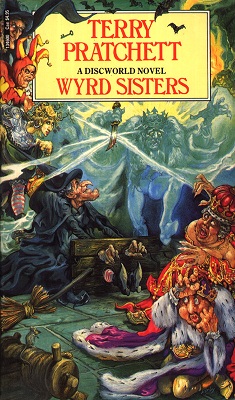

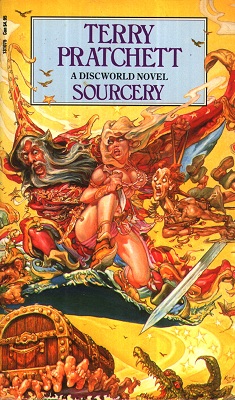

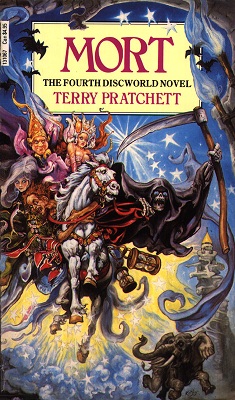

A word about Josh Kirby is needed at this place. Kirby was of course the cover artist for all the Discworld novels up until his death, Thief of Time being his last novel. His work was incredibly caricatural in nature, with very exaggerated figures and bright colours, not really to everybody’s tastes. Some might have found it a bit childish even, but I always liked it. To me his covers were Discworld, especially the early novels when it wasn’t all taken that seriously yet even by Pratchett himself. Therefore it made perfect sense to do an illustrated Discworld story with his drawings, just like his replacement as cover artist, Paul Kidby, would do with The Last Hero.

Without Kirby’s illustrations, what’s left is a slight but still fun story, a clever parody of the story of Faust. It all starts when a young wannabe demonologist, Eric, tries to summon a demon from the foulest regions of hell, but through one of those million to one chances that crop up nine times out of ten, he gets Rincewind. It’s unclear who’s more shocked to find this out, him or Rincewind. But certainly no one is more shocked than Rincewind when it turns out he is indeed bound by the summoning just as a real demon would’ve been…

So he has no choice but to try and grant Eric his three wishes: mastery foa ll the kingdoms of the Earth, to meet the most beautiful woman who ever lived and to live forever. In proper Discworld fashion, none of these three wishes turn out like you’d expect, but what remains unanswered is just where Rincewind is getting the power to even attempt them. It’s all a trick of course, with Rincewind and Eric no more than pawns in a power struggle in hell, as more traditional minded demon aristocrats attempt to overthrown their current overlord, who is slightly too impressed with modern human management theories.

Eric‘s portrayal of hell reminded me a lot of Terry Pratchett’s earlier collaboration with Neil Gaiman, Good Omens, particularly in how hell’s old fashioned evil doing is no match to modern, impersonal human invented evil. As a story it’s not up to the standard set by the preceding few Discworld novel, in feel it’s more in line with the earliest ones.