Some Images Are Not Banned

Dutch blogger Martijn at Closer writes about the anthropology of Islam in the Netherlands, and has found some historical images of Mohammed, produced by Moslems in medieval times, that shed a different light on the cartoon controversy:

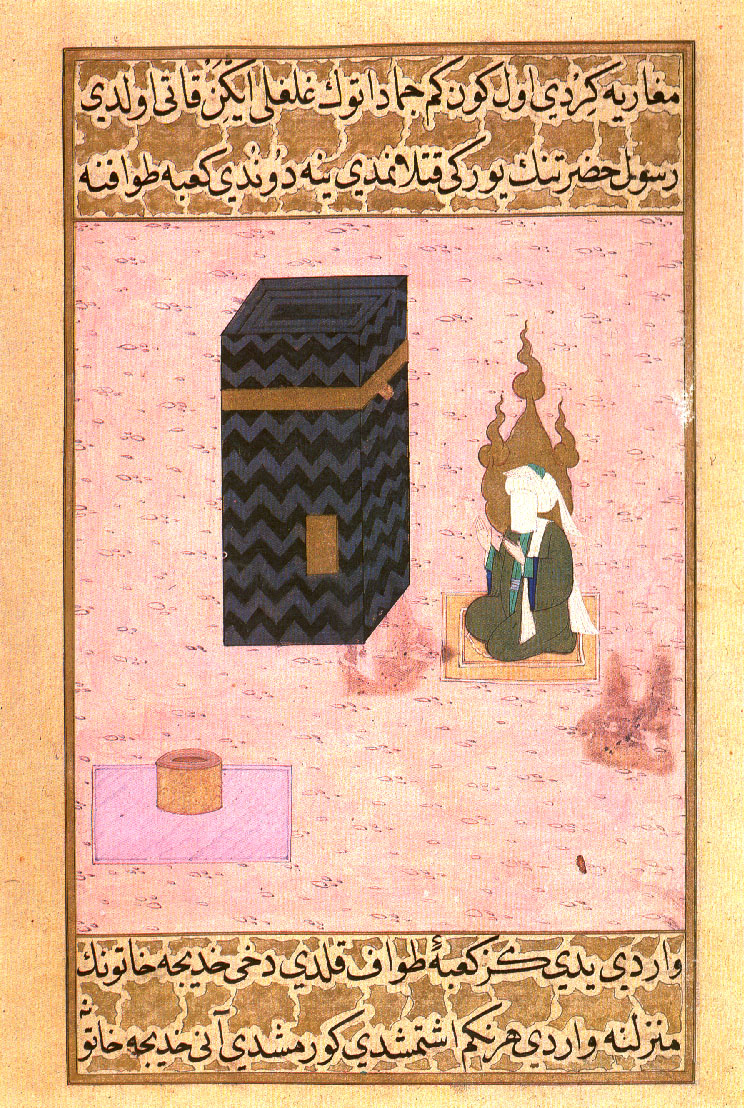

Muhammad at the Ka?ba. Siyer-i Nebi: The Life of the Prophet. Istanbul, 1595. Hazine 1222

I find these images confusing, as it’s commonly proclaimed that Islam does not allow images of people. Hovever, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has this to say on the subject:

Contrary to a popular misconception, however, figural imagery is an important aspect of Islamic art. Such images occur primarily in secular and especially courtly arts and appear in a wide variety of media and in most periods and places in which Islam flourished. It is important to note, nevertheless, that representational imagery is almost invariably restricted to a private context. Figurative art is excluded from the decoration of religious monuments. This absence may be attributed to an Islamic antipathy toward anything that might be mistaken for idols or idolatry, which are explicitly forbidden by the Qur?an.

But those pictures look a lot like icons, though, and aren’t those religious imagery? The Metropolitan Museum is a little more enlightening:

With the spread of Islam outward from the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh century, the figurative artistic traditions of the newly conquered lands profoundly influenced the development of Islamic art. Ornamentation in Islamic art came to include figural representations in its decorative vocabulary, drawn from a variety of sources. Although the often cited opposition in Islam to the depiction of human and animal forms holds true for religious art and architecture, in the secular sphere, such representations have flourished in nearly all Islamic cultures.

The Islamic resistance to the representation of living beings ultimately stems from the belief that the creation of living forms is unique to God, and it is for this reason that the role of images and image makers has been controversial. The strongest statements on the subject of figural depiction are made in the Hadith (Traditions of the Prophet), where painters are challenged to “breathe life” into their creations and threatened with punishment on the Day of Judgment. The Qur?an is less specific but condemns idolatry and uses the Arabic term musawwir (“maker of forms,” or artist) as an epithet for God. Partially as a result of this religious sentiment, figures in painting were often stylized and, in some cases, the destruction of figurative artworks occurred. Iconoclasm was previously known in the Byzantine period and aniconicism was a feature of the Judaic world, thus placing the Islamic objection to figurative representations within a larger context. As ornament, however, figures were largely devoid of any larger significance and perhaps therefore posed less challenge.

If I’m reading the literature correctly, it seems that the problem is not necessariily that a picture of The Prophet Mohammed causes offence in itself, as a picture – rather it’s that some branches of Islam feel that in making images of humans, an artist is usurping the role of God.

While I can understand that intellectually, I also think it’s utter rubbish from a theological standpoint. As a believer in an all-powerful God, surely one must also believe that God, being so all-powerful, wouldn’t allow any usurpation of his powers? To do otherwise would mean God was weak, and thus no God at all.