Politicians and socalled objective media both have been pushing hard the idea that the Euro crisis can only be solved by spending cuts and spending discipline, but luckily there’s the Washington Post to spell out the real reasons behind this:

“If adopted by other nations in the union, the deal would mean drastic cuts in European budgets. It would also spell the end of three decades of overspending that helped finance a cozy social protection system envied by much of the world.”

It has nothing to do with solving the crisis, it’s needed to destroy what remains of social democracy in the EU, by attempting to take away the power to set budgets from elected national politicians through hard spending limits and fines if these are breached. There already are some such agreements in place amongst the countries who have the Euro as their currency, but in practise these turned out to be not as hard as they were supposed to be in theory, especially not when you’re called France or Germany. The proposed plan would make it difficult to “blow the budget” even for those countries, but it will of course still be the weaker countries that will suffer more under these plans. Introduction therefore would inevitably lead to more spending cuts and more structural budget cuts even in the richer countries.

But what it doesn’t do is solving the current crisis, as Alex at A Fistful of Euros explains through examining what would’ve happened had it been in place already:

It would have been much easier to sanction the decade’s violators of the Stability & Growth Pact – Germany and France. Of course they got sanctioned anyway, but perhaps they would have had to pay a fine. Let’s be charitable for a moment and assume that this would indeed have caused them to run a lower public sector deficit. This would have changed what, precisely? Had it depressed internal demand in Germany, all other things being equal, it would have caused Germany to increase its trade surplus. A bigger trade surplus implies a bigger deficit elsewhere, and it also implies that German and French banks would have lent the private sector “elsewhere” the money they needed to buy the additional exports. An additional problem might have been that, had German bonds been in shorter supply, investors would have sought other AAA-rated assets and piled up even more bubbly mortgage-backed securities, which the banks would have been delighted to sell them.

[…]

But one thing this proposal would categorically not have done is to stop Italy or Spain or Ireland running up more public debt. Public debt fell in these countries from 1995 to 2007. Even Portugal and Greece didn’t exactly explode. Ireland would still have a budget surplus if it hadn’t massacred itself to save the banks (in part because the ECB wouldn’t help). Greece, well, perhaps, but it seems to be clear that just yelling at the Greeks is insufficient to fix Greece’s problems.

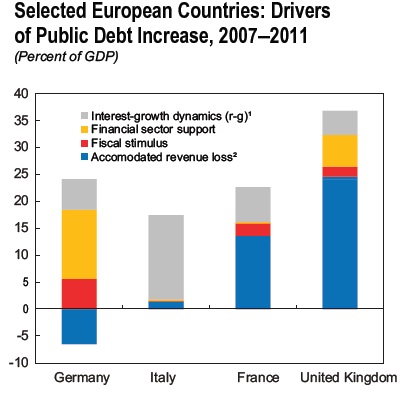

Meanwhile the chart above (From ToUCstone) shows what really drove up government debt in the four largest EU economies and it ain’t “a cozy social protection system”.

Alex

December 8, 2011 at 2:55 am“It has nothing to do with solving the crisis, it’s needed to destroy what remains of social democracy in the EU, by attempting to take away the power to set budgets from elected national politicians through hard spending limits and fines if these are breached.”

Wow, that’s depressing. I hadn’t considered that was one of the aims.