Donna Summer, dead at 63. Seriously, fuck cancer.

Archives for 2012

Lola

There’s an interesting discussion about “Lola” on Andrew Hickey’s blog, mainly about whether or not it’s problematic in its depiction of trans people:

I’ve dreaded writing about this song, because it’s witty, clever, and one of the catchiest things Ray Davies ever wrote, but it also perpetuates some negative stereotypes about trans people. However, it also shows more respect to trans people than any other pop song I could think of

Which might just be laying too much weight on what’s largely an ironic song gently mocking a young boy having his first encounter with what I always thought was a male transvestite, what with the last line of the song being “But I know what I am I’m glad I’m a man and so is Lola”. It’s the old story of boy meets girl, boy discovers girl is also a boy, boy discovers he couldn’t care less: well, nobody’s perfect.

If you look at it unfavourably, I guess you could say that it enacts that hoary old homo and transphobic fear of straight men being “tricked” into having sex with somebody who’s “really” a man, something that used to be a staple of bad American raunch comedies (or even the Police Academy series).

But I think that’s completely missing the point of “Lola”, which is really about love conquering all, gender not mattering and becoming fluid anyway (“Girls will be boys and boys will be girls, It’s a mixed up, muddled up, shook up world except for Lola”). It’s all done with a wink and a smile, but at its heart it is accepting of trans people more than you could say it is damaging.

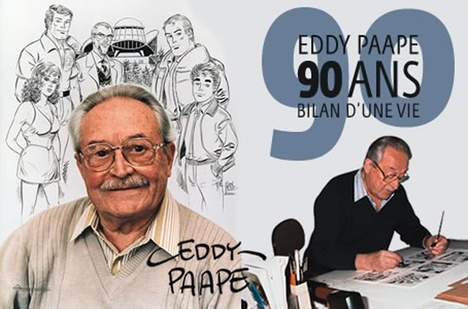

Eddy Paape 1920 – 2012

To be honest I wasn’t sure he was still alive, but Tom Spurgeon has just reported his death last Saturday, with a very nice obituary in which he called Paape “one of the last remaining ties to the initial heyday of 20th Century French-language comics publishing”. You might best compare him to somebody like Don Heck, an artist with decades of good, solid work under his belt, never quite in the first rank of cartoonists perhaps, but with his own charm nonetheless.

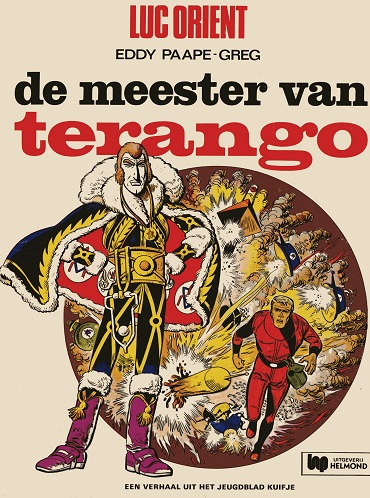

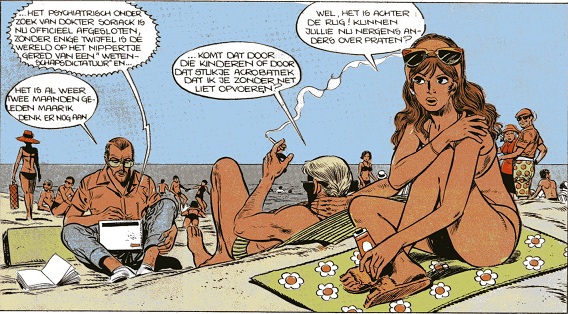

Paape had worked on both Spirou and Tintin weekly comics magazines, the Marvel and DC of Belgian-Franco comics, with Tintin being slightly stuffier and a little bit more respectable. While Paape got his start at Spirou, it was Tintin were he left his mark, starting in the mid-sixties when Greg, the Belgian Stan Lee, took over the magazine as editor/writer and revamped it with more adventure stories, modish and stylish, of which his and Paape’s Luc Orient was one.

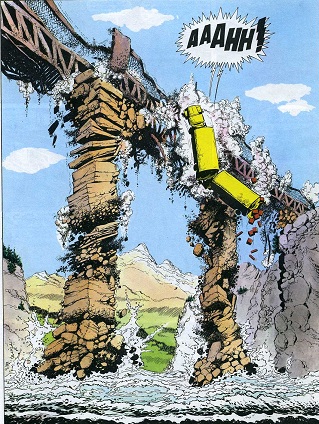

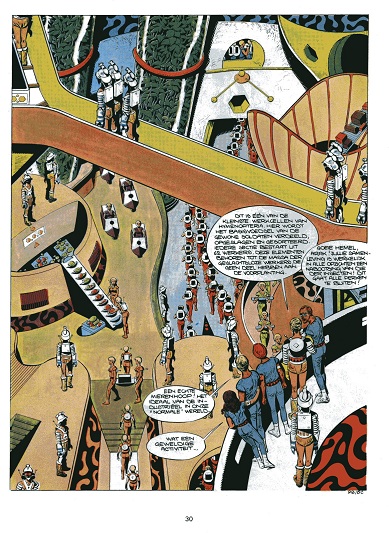

Luc Orient has the traditional three man band structure of many European adventure comics, with Luc Orient as the smart, strong, straight but slightly bland leading man, professor Hugo Kala as the brain and occasional comic relief, less physical than Orient but still a man of action and finally Lora, Kala’s secretary and Luc’s friend/love interest, feisty, independent and not nearly as often kidnap bait than e.g. Sue Storm used to be. All three work for Eurocrystal, the leading European science laboratory, in which capacity they go on strange adventures. What sets it apart is that from the start the series was orientated (sorry) towards science fiction, as well as running multiple album storylines at a time when most European series solely dealt with standalone stories.

I discovered Luc Orient in the same way I read most comics as a child: through the local library, together with series like Valerian and Les naufragés du temps. Of those three Luc Orient was the easiest to get into, thanks in no small part to Paape’s artwork. At first sight it looks slightly flat, a bit stilted in its composition and with stiff figures, but if you give it a change you’ll find out that this is a deliberate stylistic choices and that it works well in giving an grounding of realism to these science fictional stories. He was great at drawing technology, real or imagined, some of his design sense surely influencing later science fiction series.

Luc Orient was and is one of my favourite science fiction comic series and I still love the look of Paape’s artwork. For me, Paape was one of the cartoonists who defined what modern Franco-Belgian comics from the late sixties would look like.

Why London?

From Lavie Tidhar’s “some Notes Towards a Working Definition of Steampunk”:

Nicholls does go on to say that “it is as if, for a handful of SF writers, Victorian London has come to stand for one of those turning points in history where things can go one way or the other, a turning point peculiarly relevant to SF itself.” It could indeed be argued that, while not all Steampunk or Steampunk-influenced novels are set in Victorian London, the city, to a large extent, dominates these narratives: “a city,” Nicholls observes, where “the modern world was being born.”

But if steampunk is indeed a mulligan on the industrial revolution, a do-ocer to get all the cool toys we didn’t get in the real world (brass computers! armoured zeppelins! cogs on shoes!) as Kip Manley has it, than London surely is the wrong city to use. The industrial revolution happened up ‘orth, in the Midlands, in Lancastershire and Yorkshire, not in the capital, but in the grimy horrible industrial towns and cities Pete Wylie lists here.

Not that London didn’t have industry of course; just that the schwerpunkt of the industrial revolution was never there. Which makes the central role it plays in steampunk imagination all the more strange, until you realise most steampunk writers are as much influenced by Sherlock Holmes as real history. London fits the middle class conciets of steampunk, the desire to have an industrial revolution without the industrial classes. In that regard, London was indeed the city where the future was being born.

Middelburg loot

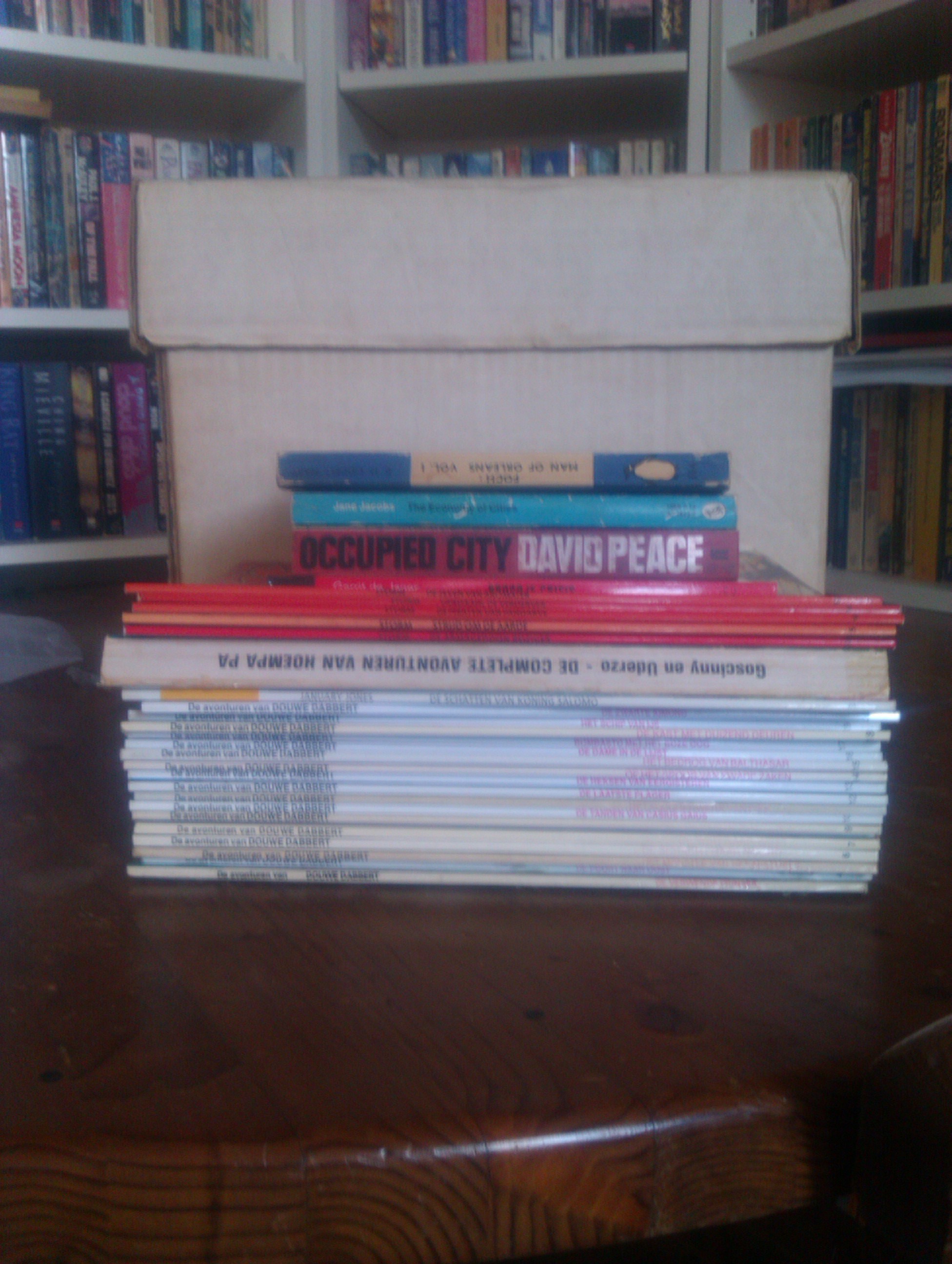

Going back home to my parents always means an opportunity to look at the secondhand bookstore there (singular, as there can be only one). This weekend was a good one. I found a nice stack of comics, as well as some other neat books.

What I found were fifteen or so Douwe Dabbert strips, an old serio-comic adventure series written by Donald Duck editor Thom Roep and drawn by Piet Wijn, one of the old grand masters of Marten Toonder’s animation and comic studio. These stories were serialised in the Donald Duck weekly magazine, which always included a non-Disney strip like this, aimed at slightly older readers, in its back pages.

On top of those is a January Jones album, barely visible under the big Goscinny/Uderzo Oumpah-pah omnibus. The latter is sort of a prequel strip to Asterix only set amongst “Red Indians” in French North America. January Jones on the other hand is a retro-adventure ligne claire strip that ran in Sjors en Sjimmie in the early nineties, drawn by Eric Heuvel and written by Martin Lodewijk, one of the Netherlands best scenario writers, who also worked on the Don Lawrence Storm series, the last issues I still needed to get I also found this weekend.

Finally, on top of those there’s a Gerrit de Jager cartoon collection of the strips he did for a newspaper about the economic recession and some normal books: Jane Jacobs The Economy of Cities, David Pearce’s Occupied City and Foch: Man of Orleans by B. H. Liddel Hart.

The box behind all this is a short comics box filled with a mere fraction of the collection of floppies I still have stashed at my parents. I spent an hour on Friday digging through my longboxed and taking out some favourite series and sequences, things I knew I wanted to keep. One of these days all of them need to be moved here, or gotten rid off. The dillemma of every aging comics collector: what do I want to keep, what can I live without.