On a cold, bright Thursday morning, I said goodbye to Sandra.

Archives for 2012

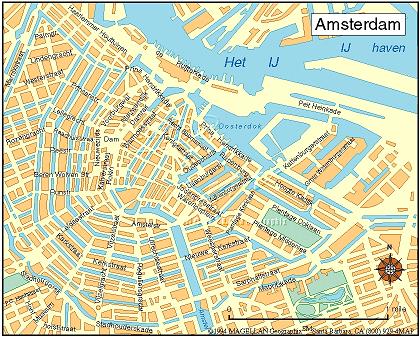

Noord isn’t quite Amsterdam

Lonely Planet have just called Amsterdam the second best city to visit in the world, but in Amsterdam, Amsterdam Noord is a bit of an ugly duckling, never really considered part of the city. It’s located over the IJ, the main riverway running through the city and therefore separated from the rest of it, historically consisted of various small villages that were almagated into Amsterdam and traditionally has been one of the city neighbourhoods more troublesome inhabitants had been banished to. Apart from that, it has always been dominated by heavy industry: the old Fokker aircraft factories used to stand not far from where I live, while the Shell factories have only be recently demolished to make room for houses. For most part, if you didn’t live in Noord, you had no reason to go there.

This is all slowly changing though. In the past decade Noord has become somewhat desirable, as the usual gentrification subjects — students, hipsters, artists, upcoming yuppies — discovered that it had some of the last low priced but attractive neighbourhoods left in the city, while the municipal authories have been doing their best to get the socalled creative classes and industries to settle in what were once places of heavy industry. In all this they’ve been helped by the coming of the north-south metro line, which will make Noord that much more accessible from the city centre. In the neighbourhoods around the line there has been an influx of first time house buyers; in my own neighbourhood I’ve seen the older working class retirees, as well as the first and second generation Moroccan families slowly disappear to be replaced by a lot of young Surinam-Dutch families as well as *shudder* hipsters.

I quite like living here, in not quite Amsterdam, but still only ten-fifteen minutes by bike from the centre. Somewhat poorer perhaps than some of the other parts of town, fewer amenities — no neighbourhood pub! — but a good neighbourhood to live in and slowly getting better.

The Strategic Steam Reserve — myth or legend?

It’s November 10, 1983. The Soviet leadership has completely misinterpreted the NATO exercise Able Archer as preparations for a sneak nuclear attack and preemptively launched a first strike the day before, hitting targets in Western Europe and Britain, but not yet in continental America. Completely nuclear armageddon is narrowly avoided, but if you’re living in Europe, you’re out of luck. Britain has been hit less but the attacks still have left millions dead and the national infrastructure devastated, not in the least because the electromagnetic pulses of all these nuclear weapons going off have fried everything electronic in the country: planes can’t fly anymore, cars and trucks don’t have petrol to run on anymore, while diesel and electric powered trains have also been fried or no longer have power to run. There’s only one transport system that has escaped the war unscathed: the steam locomotive.

Steam locomotives are after all 19th century technology, completely mechanical, without electronics to fry. So it’d make sense that in a rail dense country like the UK, they could be used after a nuclear war to help rebuild the country. Moreover, Britain has huge coal reserves, so no problems with powering them. Finally, Britain was late in switching from steam to diesel and electric powered trains, the switchover only completed in the sixties and seventies. There were quite a lot of modern, new steam locomotives that could be mothballed and kept in reserve.

On the face of it therefore, especially knowing that the UK had made extensive preparations for rebuilding a post-nuclear war Britain, the idea that, like Sweden or the USSR, that somewhere in Britain there were stockpiles of steam locomotives waiting patiently for the day after.

But did Britain really have a strategic steam reserve, or was it just an urban myth? On an Ukranian expat forum, they think it did. At a more conspiracy minded website they’re undecided, but one Robert Moore pours cold water on the whole idea:

However, there are also some notable drawbacks in relying on the rail network as a means of transportation following a nuclear war. To begin with, we can suppose that most of Britain’s population-centers would have been hit during an nuclear exchange. Also gone – of course – would be the tracks leading to them; tracks that were specifically built to connect these settlements to other parts of Britain. Additionally, much of the “surviving” track could be very seriously heat-damaged, either warped by heat directly radiated from (probably) multiple nuclear explosions, or by the firestorms, which follow afterwards. The latter are likely to ravage large tracts of the U.K following a nuclear strike, and would inflict almost as much damage as the warhead detonations themselves! In regards to this, it should be remembered that most trackways have interconnected wooden components, which would both fuel and channel the direction of a fire along them (especially if they were exposed to a nuclear-generated “heat-blast”). Furthermore, shock-blasts generated by nuclear detonations are likely to radiate for miles from the explosion’s “ground zero” point. A force capable of smashing houses to rubble and matchwood is surely more than capable of dislodging exposed railway tracks!

Therefore, it is probable that the British railway network would require extensive repairs before it could even be seriously used again…

There are other reasons why, if such a steam reserve existed it would be not as useful than you might think and it can best be summed up by the below map, which shows the absorption of black carbon in the atmosphere (PDF) (and subsequent dropping of global temperatures) after a limited nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan.

Perhaps

Perhaps some day the sun will shine again,

And I shall see that still the skies are blue,

And feel once more I do not live in vain,

Although bereft of You.Perhaps the golden meadows at my feet

Will Make the sunny hours of Spring seem gay,

And I shall find the white May blossoms sweet,

Though You have passed away.Perhaps the summer woods will shimmer bright,

And crimson roses once again be fair,

And Autumn harvest fields a rich delight,

Although You are not there.Perhaps some day I shall not shrink in pain,

To see the passing of the dying year,

And listen to the Christmas songs again,

Although You cannot hear.But, though kind Time may many joys renew,

There is one greatest joy I shall not know

Again, because my heart for loss of You

Was broken, long ago.

Perhaps (“To R. A. L. Died of Wounds in France, December 23rd 1915”) is a poem by Vera Brittain, composed after the death of her fiancé during the First World War. I came across it while reading Singled Out by Virginia Nicholson, a book about the “generation of spinsters” that war left in its wake in Britain. It seemed a fitting poem to mark the occasion of Sandra’s death a year ago today.

Would’ve been even better with squid

You know how, when you see those documentaries in Shark Week at Discovery, they’re always tagging and putting radio beacons on sharks? Well, now you can follow those tagged sharks all over the ocean. Isn’t the future wonderful.

Also: how to bathe a hedgehog: