Asterix and Obelix cross the Channel into Brittannia to help out their cousins in a rather jolly adventure. Good show old chum!

It turned out that yesterday was the 65th anniversary of the first publication of Asterix in Pilote, which I only realised after I had already published yesterday’s post. A day late then, a happy anniversary to Asterix. It’s hard to overstate how important this was. Not only has Asterix become a national hero of France and the most popular European comics character of all time, even beating out Tintin, but thanks to him Pilote could break the Belgian Spirou/Tintin duopoly. These two magazines had captured most of the European (or at least the French part of it) comics market post-war, creating the Golden Age of Belgian comics during the fifties. By 1959 and Asterix‘s publication however they both had grown a bit stale. The challenge that Pilote would reinvigorate Tintin and Spirou as well.

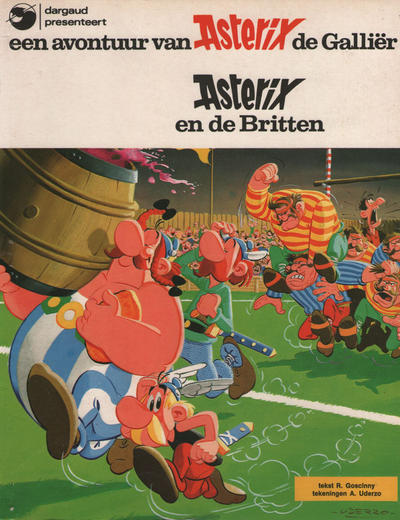

Asterix en de Britten is a good example of why Asterix became so popular so quickly. First you have the story itself, set just after Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain. As with Gaul he quickly conquers most of the country except for one tiny village courageously resisting. Sadly, without a druid capable of creating a magical potion that gives them super strength, their outlook is bleak. Luuckily, Notax, one of the village’s inhabitants is a distant cousin of Asterix and rows to Gallia to get his help. Panoramix the druid creates a cask full of the potion and Asterix and Obelix volunteer to bring it and Notax back to his village. Back in Brittania they promptly lose the cask and go through all sorts of adventures to get it back.

That on its own is fine, but it doesn’t set Asterix apart from similar series. What makes Asterix such fun is its sense of humour, which is a cut above the usual slapstick antics of other humouristic adventure series. Not that it doesn’t like a bit of physical comedy, but it’s not the only thing it does. There are the character names for example, usually a pun of some sort. There’s the referential humour, one panel here showing “a quartet of popular bards”, clearly the Beatles. In this story, there’s the gentle ribbing of English stereotypes: Obelix complaining about boar being served drenched in mint sauce, the poor creature, the lukewarm beer, the Brits breaking off their fight with the Romans for a tea (well, warm water) break…

But the best part is that Goscinny gives his British characters recognisable English speech patterns and sayings. And the unnamed Dutch translator has managed the same, e.g. translating “I beg your pardon” as literally “ik vraag uw pardon” or “rather” as “nogal”. They also speak much more formal then either the Gauls or the Romans, further distinguishing them. It takes some time to notice, but once you do it’s rather amusing.

Asterix is one of those series almost every Dutch child has read at some point and I wasn’t an exception, always happy to read a new one. The great thing about them is that I can reread any of the classic Goscinny/Underzo stories and still enjoy them as much as an adult. Sadly Goscinny passed away far too early in 1977, aged just 51, after a botched operation. Uderzo, the drawer, continued the series on his own but it was never quite the same to me. He retired in 2011 at age 84 from the series and would live until age 92, dying in 2020.

No Comments