If Shirobako was about keeping your love for anime while working in the industry, Eizouken is all about the pure love for anime and why anime is worth loving.

Yuasa Masaaki. This is the second or third series of his I went in blind only to be knocked out by the sheer majesty of his imagination. Devilman Crybaby, two years ago, was the last time that happened. I went in only having seen the cute pictures of monster girls and their girl friends on anitwitter and was completely unprepared for the maelstrom of feels that happened when I binged it one Sunday. For Eizouken ni wa Te wo Dasu na! I only had the MAL description to guide me, which made me think it would be a more fluffy Shirobako. A slice of moe version if you will, cute girls in a high school club making cute anime together. And while there are school girls, an anime club and a desire to live your life to the fullest doing what you love, it’s all a bit more hard edged.

What it shares with Shirobako is its love for anime. The scene shown above was basically my experience watching this. There’s so much to like in this scene. First, there’s the simple pleasure of watching the protagonist Midori settle down for a night casual anime watching, only to get drawn in slowly to the point she almost crawls into her screen to see everything better. Second, the fact that it’s Mirai Shounen Conan/Future Boy Conan, a 1978 anime series directed by Miyazaki Hayao. Finally, that it takes the time to actually show scenes from the anime, lovingly recreated and still recognisably in the style of the original. You see Midori fall in love with anime and you see why she falls in love with it, why a 42 year old anime could stir her this way. I don’t know why exactly Mirai Shounen Conan was chosen as the series that made her fall in love in anime, but it fits so well. The town or city that Midori lives in could as easily be part of the world of Conan, it has the same sort of aesthetic, though it also reminded me a little bit of some of Moebius works.

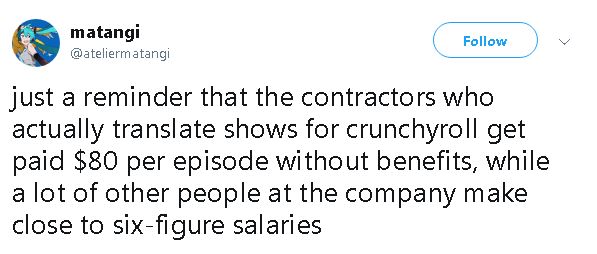

The true story only starts with a time jump to Midori just starting high school, badgering her friend Kanamori to go to the Conan showing in their school’s anime club, not wanting to go by herself. Kanamori agrees, but only if she treats her to no less than four bottles of milk from the local bath house. Kanamori is a bit mercenary, hard headed, not that interested in Midori’s obsession with anime, but a good friend who goes along to support her. When she asks what Midori actually enjoys about all this, the result is the rant above, where she painstakingly and in great detail explain just what makes Mirai Shounen Conan so good until her friend stops her.

What’s so great about this is that Midori’s rant is one you could’ve read on Sakbugabooru. It’s all about the art of animation, not the cool plot or cute characters, let alone the usual otaku consumerism. Midori is all about how the animators create a whole world by taking reality and “exaggerate it in a way that makes sense”. As we watch the same scene with the antigravity vehicle they’re watching, we have Midori explaining that by picking it up as if you would try and push a car to get it to run, you lend it an air of realism. She elaborates further, as we watch a typical Miyazaki impossibly big airplane take to the sky and Conan running around on its hull, how the way the plane moves and debris circles around it again makes it believable, with the sheer physicality of how Conan moves atop of that ship makes you accept it when it’s clearly impossible.

And the best part is that having explained and set out all these rules, the show immediately goes and demonstrates how to use them. Everything Midori said about Conan goes for her own series as well, up to and including the idea of “seeing a character wandering around a mysterious world filling you with a sense of adventure”. Most obviously in the chase scene right after Midori’s rant, as she and Kanamori run into Tsubame Mizusaki, child actress & model. Mizusaki’s parents have forbidden her to join the anime club and now her bodyguards are chasing her to stop her doing her so. As she’s confronted by the head bodyguard in some sort of theatre stage, the other two rescue her, being chased by the guard, fleeing to the top of the stage. As the guard approaches, Midori pulls a rope and opens a trap door, which he avoids. She pulls another which does nothing useful, he smirks but as she pulls the third rope, the steps collapse, forming a slide and he slides down them into the trap door. It embraces all the principles Midori set out just before and adheres to the rule of three of comedy. It’s a neat, physical scene in an episode that has a lot of talking heads otherwise.

Once the three escape Mizusaki’s minders they take her to a laundrette to clean her strawberry milk stained school shirt. It’s there that she and Midori bond about anime, showing each other their sketch books. Whereas Midori is all about concept art, Mizusaki is more about character sketches and the like. As Kanamori looks on, she asks whether they would like to make an anime together. Midori demurs, but Kanamori asks if not now, when and she has a point. As high school amateurs they have nothing to lose, nobody expecting anything from them, so if they fail, so what?

Her little motivation speech leads to a bout of inspiration for the other two, bouncing of each other’s ideas to create an entire world from a small doodle in Mizusaki’s sketch book. I’ve included the start above, but the full sequence runs over five minutes. As they creating, Mizusaki asks about Midori’s interest in concept art and she answers by asking if she ever created layouts for a secret base as a child. For Midori, concept art is her creating a whole new world as best as she can. Even before she got into anime we saw her sketching and mapping her new city. Having somebody to do this with must be heaven for her.

When the scene switches from them creating a new world to them having an adventure in that new world, we once again see everything that Midori ranted about earlier, everything that we saw in those Mirai Shounen Conan excerpts, being done here as well. The vehicle they created should not, could not fly as it does here, but it works because the way it behaves is consistent with the visual cues we are given about it. When one of the wings is damaged and no longer works, Mizusaki and Kanamori jump out and use their body weight to shift the vehicle, so they can fit through a narrow crevice in the landscape. You can feel them do it as you’re watching. It feels right.

Honestly, something very good has to be released this year for Eizouken ni wa Te wo Dasu na! to not be my anime of the year at the end of it. This is not just a good anime, it’s something that completely rekindled my love for anime, made me excited about anime after a year in which I watched much less anime than I used to. I was a bit burned out on it all, but this was just what I needed. Having characters fall in love with anime to the point of wanting to create it themselves, without all the usual otaku nonsense surrounding it, is so refreshing.