About two thirds of the way through watching the entire series of Gatchaman Crowds I started to realise that it was actually a classic Hegelian dialectic masquerading as a manic pixie dream girl rom-com, with the Gatchaman superhero team in the role of the dour salaryman shaken up out of their boring routine. In the grand tradition of Japanese superhero shows, the Gatchaman team is fighting a secret war against an alien menace, the MESS, computer generated LEGO blocks fond of abducting people, barely managing to keep the status quo. They’re super serious about following the rules for how superheroes should behave, none more so than this guy, Sugane Tachibana, who is the first to come into contact with our manic pixie dream girl.

Cast in that role we have Hajime Ichinose, the latest Gatchaman recruit, who of course goes to the same high school as Tachibana. Cheerful, energetic and much, much smarter than any of the Gatchaman first give her credit for, she blithely disregards all of the conventions that Tachibana and the others try to drill into her. It’s immense fun watching her stroll through the first two episodes, making contact with the MESS and revealing that the entire reason for the Gatchaman to exist was based on a misunderstanding, as the MESS apparantly never realised the people they abducted were sentient. Hajime gets them all back, leaving the team jobless, but not for long. There’s a new alien menace, Berg Katze, a renegade Gatchaman, who delights in murder & mayhem, wanting to see the Earth go up in flames as he manipulates a war of everybody against everybody, starting with the Gatchaman’s own Tachikawa City. But even this menace doesn’t cause hajime to change her outlook on life: she remains cheerful, optimistic and wanting to communicate, to understand Berg Katze.

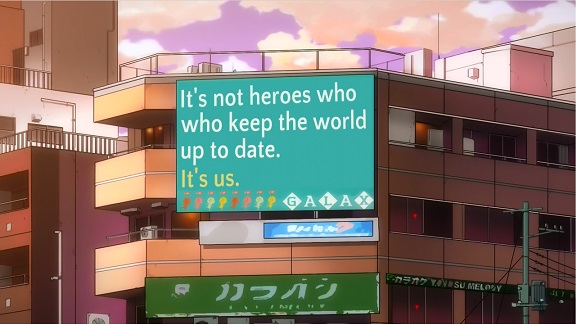

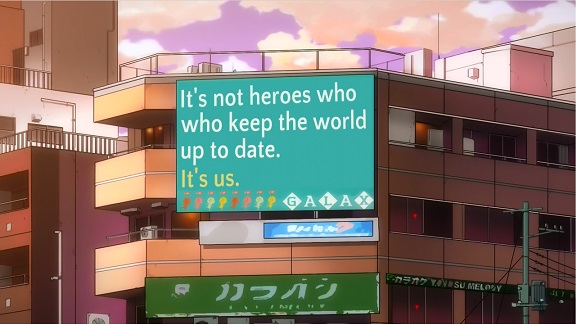

Of course what would a rom-com be without a love rival? That’s the role of Rui Ninomiya, the genius behind the GALAX social network that Haijime is a huge fan and user of. Rui is perhaps best described as an internet utopian, with their GALAX network enabling its users to help each other through the gamification of altruism, people getting points for e.g. assisting with a traffic accident. Rui believes that the world is flawed and wants to “upgrade” it through GALAX; they don’t believe in leaders or heroes. Judging from their appearance, they’re genderqueer, with the subtitles refering to them with both male and female pronouns, which the show presents matter of factly without drawing attention to it; that’s just how Rui is.

Getting back to the Hegelian dialectic, we have the Gatchaman team, with Sugane Tachibana as their spokesman, providing the thesis: the world needs heroes to protect it from alien threats and other menaces. These heroes need to keep their identities secret to be able to operate, as well as keep their battles secret not to worry normal people. You need rules, you need to be serious, you need to realise this is a life and death struggle and act accordingly. Saving the world is serious bizniz.

GALAX and Rui Ninomiya then provided the antithesis: we don’t need heroes or leaders, normal people are capable of solving their own problems, even an existential threat like this, as long as you give them the tools and trust them to use them. Be flexible, be creative, have fun and problems will disappear almost of their own accord.

The synthesis comes of course courtesy of Hajime Ichinose, who from the start has been able to mash up those two philosophies and transcedent them. In the second episode she takes Tachibana to her collage group’s meetup, where to his surprise he learns the mayor and fire chief are part of it, while in the same episode we also see her noting how well connected and near to each the city’s various power centres are. It’s a subtle foreshadowing of the role she plays in the second half of the series, at home both with the flexibilty and grassroots power of GALAX and using more traditional power structures. For her it is self evident that if the world needs heroes, they should be public and not ashamed to use their real names, but also that if you want to trust ordinary people with the power of GALAX, you have to give them that power, not try and establish a new elite with it.

That’s what I like about Gatchaman Crowds and Hajime especially, that seeing straight through hypocrisy or contradictions to the heart of the matter. In the end this is a optimistic show, celebrating the ability of people to come together and work for a common goal, seeing the good in both tradition and innovation. Hajime Ichinose is the embodiment of this clear eyed but optimistic vision.