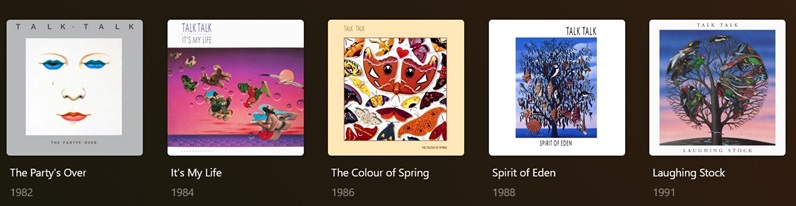

It’s been a grey, cold day today and I’ve been listening to Talk Talk, all five their albums in chronological order. Talk Talk always feels autumnal to me so this was the perfect day to put them on.

Now critics always go on about how different each Talk Talk album is from the next, especially the last two from the first three. And indeed, when you listen to Laughing Stock (1982)after The Party’s Over (1991), they don’t sound as if they’re made by the same band. But when you listen to them in order, you can see an evolutionary line in there, one album following logically from the previous.

The Party’s Over is very of its time, big flat drums and lots and lots of synths, but it already contains the seeds for the next two albums, It’s My Life (1984) and The Colour of Spring (1986). These two keep the big, open sound of that debut but dial back on those drums and synths. Spirit of Eden (1988) meanwhile is much more withdrawn and quiet, but its A-side follows logically from The Colour of Spring‘s B-side which already started quieting down.

If you only know the big radio hits and then stumble across those last two albums I can understand why they sound so out of left field, but in context they build up logically from those very first beginnings. Listening to them I really couldn’t tell where The Colour of Spring ended and Spirit of Eden began.

In conclusion: Mark Hollis was a genius and Talk Talk one of the best bands from the eighties.