Take a good look at the picture above. That’s going to be the last scenes we’ll see of Raccoon City spread out in the daylight. Soon the cars will go into the suburbs to collect the Umbrella Corporation scientists living there to evacuate them out, leaving the city behind to succumb to the zombie apocalypse. Once that happens it’s all crowded sets, claustrophobic close ups and darkness. But for now it’s still bright, sunny and empty, only those black cars moving in ominously.

Our first good look at Jill Valentine comes about seven minutes into the movie, after we’ve had the short recap of the first movie, the set up for this one, the black cars have picked up their cargo and the zombie eruption is in full process but not yet recognised. This is the first clear shot of her face, after she’s stormed the police office she used to work for and shot all the zombies being arrested there, her former co-workers still thinking they’re normal criminals. Before that we only saw her in extreme close up: feet in high heels climbing stairs, her arms as she turned on her telly and grabbing a gun when realising what’s going on, cropped shots from behind as she moves into the office and starts shooting. A much more action orientated introduction than that of Alice in the first one, naked and vulnerable waking up in the shower.

Resident Evil: Apocalypse is a very different movie from Resident Evil; Aliens to its Alien, a survival action story rather than a horror story. The first took its time to start the action, ratching up the tension slowly. Here it starts almost immediately. The first fifteen minutes or so of the movie is all action scenes as we get to meet the main characters and see the apocalypse starting to gather steam.

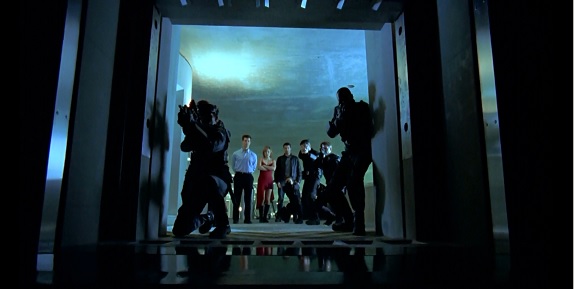

All of which culminates in this scene, in which Raccoon City is closed off by orders of the Umbrella Corporation. It’s a scene that neatly encapsulates both the inherent inhumany of Umbrella and its executive corps, but also its inherent incompetence and stupidity. First of all, closing off the entire city biut for one, not very big escape route isn’t going to get very many civilians out of the city, but then Umbrella is more than happy to sacrifise its own troops on the slightest pretext, which doesn’t say much for the intelligence of its goon squads. And then there’s the arrogance of the main villain to stand there in his business suit in front of an armed, angry and scared crowd telling them they’re going to die. Had I been there with a gun, that fecker would’ve been the first to die…

Alice and Jill finally meet a third into the movie, as Alice saves Jill and co from an attack by some of the super zombies. As seen in the epilogue to the previous movie and re-established here, she’s been experimented on by Umbrella and turned into a superhuman. It’s another case of Umbrella stupidity because of the way they went about it. The shock ending of Resident Evil had her and one other survivor break out of the Hive, leaving it and its zombies sealed behind them, only for the company to attack them and immediately use them to experiment with the T-virus. Had they been slightly less muhahaha evil and taken the time to debrief Alice, they’d known what was waiting for them in the Hive, they wouldn’t have let the zombies reach the surface and this whole movie would’ve been much shorter.

One of the things the

It of course all ends in a fight to the death on the roof of some modernist office building monstrosity, as the main villain forces Alice to fight his super zombie monster that he’d already taken for a field test in the last third of the movie. The symbolism here is …not subtle… You got the heavy, bulky, (barely) remote controlled killing machine squaring off against the woman who throughout the movie has tried to keep civilians and innocents alive, no fighting for the lives of her friends and comrades. The forces of evil seem to have all the power, but Alice’s own innate compassion wins the day in the end.