Right-wing conventionals see moral instruction as paramount in a story, and left-wing conventionals see immoral instruction as paramount to avoid in a story. Both positions can only come from the heads of poor readers. It is useful to point out “preachiness” on the one hand and potential offense on the other, especially when the author may not even realize that they are either preaching or offending, but conventionalists rarely stop at the text. Every story in a workshop is some sort of ethical litmus test, and even when there is no outrageous content there is often outrageous aesthetics. Is first-person fascist because it TELLS the reader WHAT TO THINK?? Certainly not, but I’ve heard this declared from liberal nitwits. Is anything other than third-person objective point of view in past tense told with “plain language” somehow sign of a homosexual/Communist plot? Anyone who has ever read one of the rambling semiliterate editorials in Tangent knows the answer to that! And let’s not forget the tyranny of “story” which conventionals always chirp abut. The morons even go on about Shakespeare as some sort of populist cartwheeler, as if people still look at Romeo and Juliet for the plot, which is “spoiled” by the author himself anyway in the Prologue. (“From forth the fatal loins of these two foes/A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life.”)

Art & Criticism

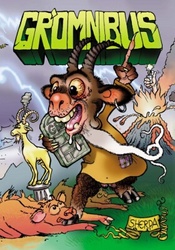

Gr’unn!

A can’t miss bargain to be had at De Slegte in Amsterdam right now: copies of Gr’omnibus, a treasure trove of sequential art from Groningen, the Athens of the North; an invaluable treasure now yours for only two euro fifty! Why you should bother? Because you get to sample some 40 odd (some very odd) Dutch (as well as the occasional furreign) cartoon talents, culled from the pages of one of the most consistent of Dutch underground comix zines, G’runn.

Most foreigners might be forgiven for believing there’s not much more to the Netherlands than Amsterdam, Den Haag and perhaps some pittoresque village like (ugh) Volendam, with Zeeland thrown in for free for our German friends who tend to encamp on the beaches there each summer in a more benign re-enactment of the Maydays of 1940, but there are other interesting cities in the rest of the Netherlands as well, even up North. Groningen (Gr’unn in the local dialect) is one of them, a university town big enough not to be overwhelmed by it with a decent local art scene and nightlife, a city in which over the years a thriving alt-comix scene has been established.

In 1996 a few of them started Gr’unn, which since then has published a lot of up and coming cartoonists. People like Barbara Stok, Mark Hendriks, Amoebe, the Lamelos collective, Marcel Ruijters, Reinder Dijkhuis, Berend Vonk, all had strips in Gr’unn. And as such it helped establish, together with Zone 5300 and more amateur zines like Impuls or Iris, the first generation of cartoonists neither interested in going the traditional comics route of magazines or newspapers, nor in consciously rebelling against this, but who just went their own way.

Any anthology of a comix zine celebrating its ten years anniversary will always be uneven and of course Gr’omnibus is this as well. Some of the cartoonists are better or more interesting than others, while there’s a huge mix of styles and subjects represented as well. But there is common ground as well. Autobiographical or fantasy, stick figures or obsessive crosshatching, what most of the stories and artists present have in common is a prediliction for the light ironic and the cynical, short gag stories but with a twist of bitterness and not too much emotional investment. It’s a style of writing I quite like, though it can be a bit wearing in large doses. No real masterpieces here, but still more gems than dross and no real bad stories either.

So if you’re in Amsterdam and you want a cheap way to sample a huge chunk of the contemporary Dutch comix scene, go get Gr’omnibus from de Slegte. It’s in the middle of Kalverstraat so even tourists should be able to find it.

Paolo Bacigalupi: threat or menace?

Every few years or so a science fiction writer comes along who becomes the darling of the critics, especially mainstream critics deigning to notice the genre, but whose qualities on closer inspection seem to be mostly so much hot air. Stephen Baxter was one of those writers, praised by Locus for his hard science fiction, winning award after award in the nineties, but never doing anything for me. Today it’s Paolo Bacigalupi, praised for his realism and worldbuilding and his non-western settings. His first novel, The Windup Girl just won the Nebula and Locus Awards. All good stuff, right, but why when reading descriptions like the one below and this from a positive review do I feel queasy?

In essence, Emiko has been designed to be a supremely beautiful, compliant geisha. Obedience has been built into her DNA. Her skin has been made ivory smooth by reducing the size of her pores. Never intended to function in a tropical climate, Emiko has nonetheless been callously abandoned in Bangkok: Her patron decided “to upgrade new in Osaka.” She was then bought by the unscrupulous Raleigh, a survivor of “coups and counter-coups, calorie plagues and starvation,” who now “squats like a liver-spotted toad in his Ploenchit ‘club,’ smiling in self-satisfaction as he instructs newly arrived foreigners in the lost arts of pre-Contraction debauch.”

If not out and out racist (and of course, filtered through Michael Dirda’s review), this is orientalist to say the least, delving into the old stereotypes of the Far East and justifying it with genetic mumbo jumbo. It may just be an unfortunate element in this story, but then there’s his traveling through China story in Salon:

I’m not proud of it, but I’m a great liar when I travel. I smile and lie and things are smooth. Every once in a while I don’t just lie to smooth the way, I lie for fun. Once, I told a taxi driver in Beijing that I’d been studying Chinese for a week. This, after having painfully studied the language for four years and lived and worked (and lied) in Beijing for another year. I think I even told him that Chinese was an easy language to learn. Perhaps most people wouldn’t think that’s funny, but it was the only time a Chinese person ever told me my Chinese was very good and really meant it.

My restaurant companion looked at me more closely and asked, “And what do you think of the Chinese people?”

Cold and heartless, but nice if you’re in their clique of friends. “They’re great, too,” I said.

Which makes me go hmmm again. It’s all a bit dodgy even without the genetically engineered elephants powering factories and the huge metal springs serving as batteries…

Pushing the envelope only results in papercuts

Two comments by Jonathan M. from this thread at Torque Control brutally taken out of context:

I must admit to not understanding a) why one would write stuff that didn’t consciously push the envelope

[…]

I think that ‘pushing the envelope’ is a more useful term than avantgarde simply as a short-hand way of saying “don’t do what other people are doing”. Which is kind of a mantra for the postmodern age.

I always thought the essence of our postmodern age was the realisation that everything had been done and said already and worse, it is all still available at the click of a button, legally or otherwise on the internets. It’s pointless trying to go for the shock of the new, because there is nothing so new as to be shocking anymore; it’s a mug’s game.

New things are not in themselves more interesting than old ideas done well. Nobody will ever be surprised much by a new Terry Pratchett novel, yet I so much rather have him do several more Discworld books than attempting something novel. There’s a pleasure in seeing a familiar concept being done well.

Mainstream writers and science fiction

Typical. For the second time in a week somebody pulled a post I had set aside to respond to. This time it’s Will Ellwood who got cold feet and deleted his post on whether you can get too old to write science fiction. To be honest, it is an incoherent and rambling post, one of those where you can see the writer isn’t sure themselves what their points are, if any, but if I had to delete all my incoherent posts… Luckily Google remembers everything, because hidden in the jumble was an interesting point:

Often literary writers who have a go at writing what seems to be genre fiction get derided and mocked by genre fans for being unoriginal and clichéd. But are literary writers like Margaret Atwood, David Mitchell and Cormac McCarthy writing classical SF which is based around the question of ‘what if?’ or are they writing allegories and metaphor about the human condition which use the tools of SF as emphasis?

I would argue that to attempt to critique ‘The Road’ as a traditional post-apocalyptic novel would fail, as the novel is not an example of speculative world building and exploration, but a meditation on many themes. Not least the theme of a relationship between a dying father and his son in hopeless circumstances. To attempt such a critique would be to be genuinely and wilfully interpreting the book wrong.

Ellwood is riffing here on an earlier post by Damien G. Walter on whether or not new science fiction writers need to know their genre history:

But is knowing the history of SF essential to becoming a writer in the genre? On the one hand SF can be considered as an ongoing conversation spanning decades. It you enter that conversation without knowing what has already been said, you are not liable to say much of interest to people who have been following the arguments unfold for decades. But on the other hand if SF is a genre that seeks to find meaning in modern life, raw responses to that life might be mire interesting than viewpoints filtered through the mirror shaded gaze of the SF genre.

Ellwood argues that judging mainstream writers in genre terms when they’re attempting science fiction is missing the point, while Walters finds that it might even work in a writer’s favour to be ignorant of the genre. Both are provocative arguments in a field that has always had a bit of an inferiority complex when comparing itself to the literary mainstream. An inferiority complex fed by the frequent denial of mainstream writers dabbling in science fiction that they do so, of which Margaret Atwood is the most prominent recent examplar. It also galls that so often inferior works of mainstream writers are praised for their originality when so often they’re rote reworkings of old, old science fiction ideas and some never recognised sf writer has done it much better much earlier.

However, it’s not the 1970ties anymore and science fiction, though still routinely portrayed as an activity practised by spotty nerds living in their parents basement, has become ubiqitous, something you can’t help but be aware off, similar to how most people have some understanding of football (be it proper football or the American version) even if not interested in the game. Contemporary writers like David “not the comedian” Mitchell or Cormac McCarthy start with a much greater familiarity with science fiction than earlier writers could have. The science fiction ghetto has long since had its walls torn down and besides which, those walls have always been a lot less high than some sf fans like to believe. Heck, roughly half the writer entries in Clute and Nicholl’s Encyclopedia of Science Fiction are from outside the genre.

All of which means both Ellwood and Walters are right, up to a point. It is pointless to judge mainstream writers using science fiction as a tool for not adhering to traditional sfnal strengths like worldbuilding or sense of wonder when that’s not their intent. In Walters’ words, these writers may not be interested in joining the conversation sf as a genre is engaged in. Which is fair enough.

Yet having other priorities does not excuse a writer from getting the science fiction elements right. It is possible to critique The Road on its worldbuilding and unoriginality while still acknowledging its other strengths, to recognise that it stands in a long tradition of post-apocalyptic works, both genre and non-genre. And if people like Michael Chabon — who really should know better — insist that it isn’t science fiction, this should be protested. Science fiction’s own achievements should not be swept under the carpet just because some more literary acceptable writer has taken a shine to the subject. To be fair though, this seems to be more of a critic’s disease, with writers putting on some protective colouring not to be tarred by outdated notions about sf’s illegitimacy by those critics.

If we look at the big picture we may see that science fiction, which had a long prehistory of being proper literature before becoming a real genre in the safety of the pulp ghetto, may migrate back into the literary mainstream again, eventually just becoming one option amongst many for a writer. At the moment it’s almost where the detective story was in the seventies: acceptable for respectable writers to dabble in, as long as they don’t take it too seriously.