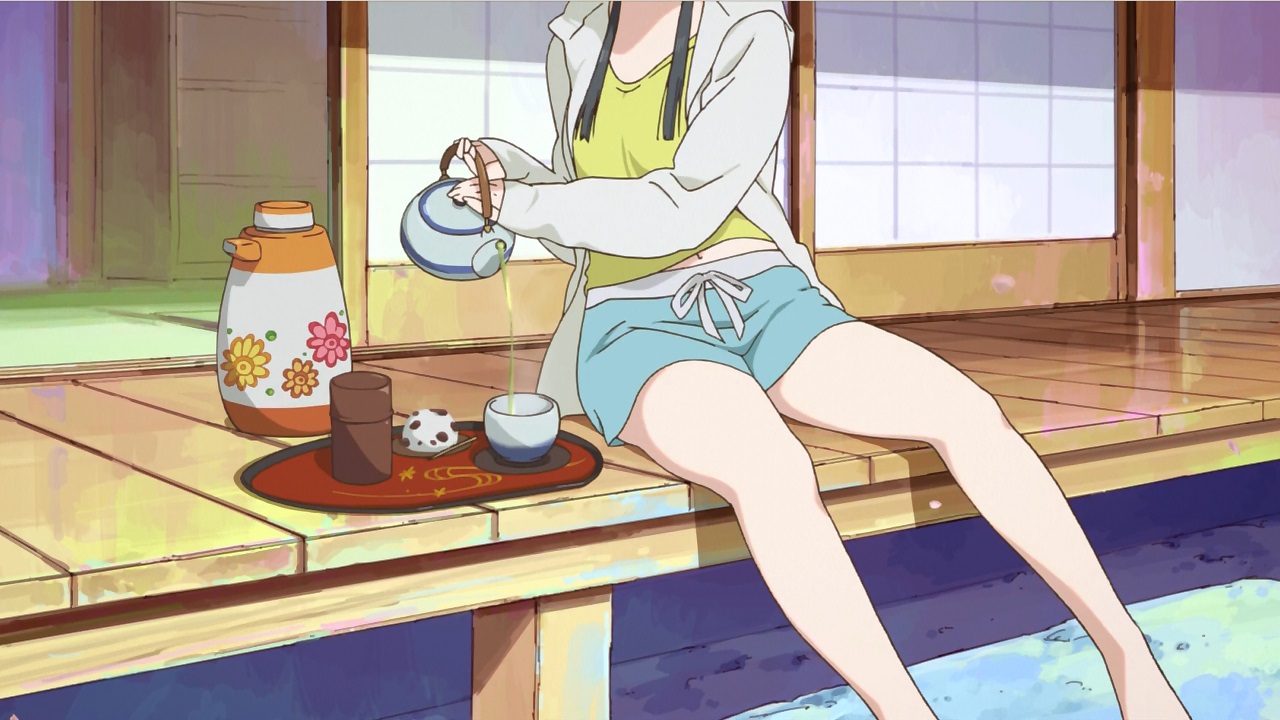

After a hi-energy opening Aiura proper opens with a few lovely landscape shots, but it’s the first look at one of the protagonists that set the mood for the rest of the show:

Horny.

Broadcast in 2013, Aiura is a short length (5:30 minutes) anime series, based on a four panel gag manga, about three high school friends hanging out and having meaningless conversations with each other. Just another slice of moe series, but for its running time. Short as it is, it’s even shorter than its runtime suggests. It has a minute long opening, a minute and a half long ending, another ending halfway through the episode which eats up another twenty seconds or so. In all, there’s only two and a half minutes for the actual show. The quality of those two and a half minutes though… For what’s largely a throwaway anime, this is really well done. The backgrounds are brilliant, the character designs are cute and the animation is very well done.

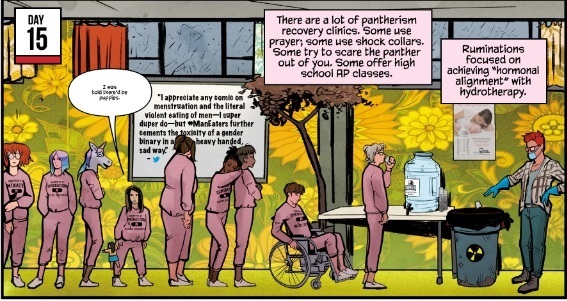

Four panel gag mangas are somewhat difficult to translate to anime, lacking an ongoing plot as they do. When done on autopilot, you just get a series of setup/setup/punch line/reaction jokes where you can almost see the panel borders. You need something to punch it up to make it work in anime. What Aiura brings is horniness. The original manga is significantly less horny than the anime. There’s little room in a four panel, top to bottom, usually cramped gag strip like this for the sort of shot as shown above after all, even had the mangaka been interesting in doing so.

The horny lens through which the anime has adapted Aiura helps keep it interesting. This could all have been static shots of high school girls talking to each other. Instead, we get shots like this, with one of the girls taking off her wet sock, lovely animated. You can see the animator likes their thighs, but the camera doesn’t leer nor do you have any of the bankrupt boob jokes you’d usually see in slice of moe series. All those slightly horny shots keep you interested while the jokes are being told.