Admittedly, it sounds like Girls und Panzer should be awful. A bunch of typically stereotyped anime high school girls are bullied by their overpowerful student committee into taken up tankery, the refined and genteel sport that makes proper women and wives out of young girls, with the main character being reluctant to enter the sport again because of a mysterious accident in her past at her previous school. Done wrong it could be an endless series of fanservice panty shots, crappy slapstick and a trite plot to justify it all.

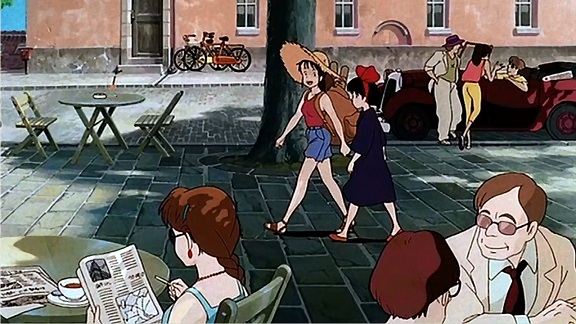

Luckily it’s better than that. Yes, the idea is silly, but the series takes it seriously, which makes all the differences. The tanks are recognisable like their real world counterpart, each with their own strengths and weaknesses and the tactics used are relatively sensible. Of course, since this is at heart a sports anime, the battles shown are more like those in World of Tanks than real warfare, something fans of the former have taken to heart. Especially because every now and again there are awesome moments of grognard nerdiness like this:

But without a good story, all this tank nerdery would be pointless. And what Girls und Panzer has is the classic sports underdog story, where the plucky newcomer with no pedigree, no experience, underestimated by the competition has to win for reasons. It’s a formula, but a well done formula: you know they’re going to win, but you don’t known how and there’s genuine tension as the odds are stacked against them. They don’t always win; there are losses too and there is a learning curve.

The characterisation, at first broad, is deepened too over the course of the series, which packs a lot in just twelve episodes (and two recap specials as the production got into trouble). Two things make it stand out from many other, similar looking anime series. The first is that all significant characters are women (only three men appear in minor parts) who work together to overcome adversary, with no sniping, no back biting, none of the silly little rivalries you see in other series. The second is that there are no villains, nobody cheating or gratitiously nasty: even the people dismissive or somewhat insulted by the newbies entering their sacred sport are won over. That’s what makes this special. That and showing how you can use a Type 89 to kill a Maus.