This is a 1992 science fiction series so the Simon Bisley cover is de rigeur even if the inside art is as different as it gets.

The first in a ten issue miniseries and the first ever Grendel story I’ve read. Bisley’s cover is what drew my eye but the interior artwork by Patrick McEown, of which more later, is what got me to buy this series.

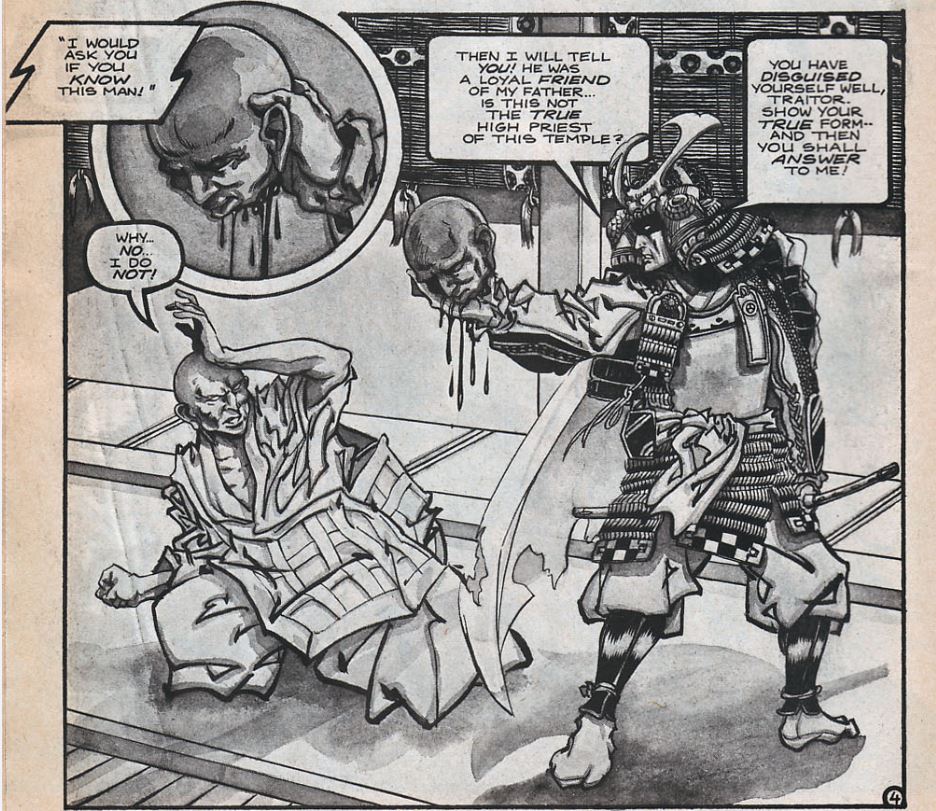

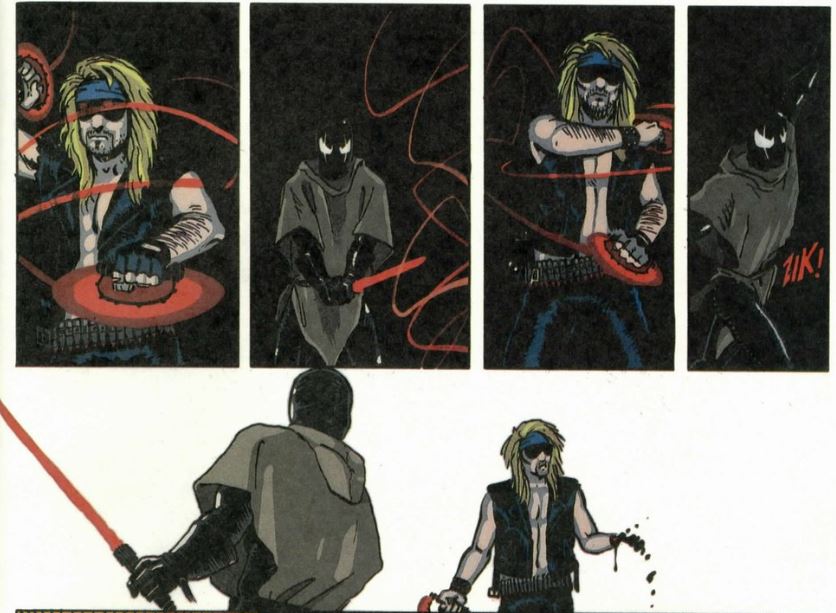

The story is simple. We open with a hover motor and sidecar fleeing through the desert. Riding it are a man dressed in black, wearing a black mask with white eyes and a boy in a hoodie. We don’t know who or what they’re fleeing until we go to what looks like a simple chalet but which hides a much larger complex below to see various murdered soldiers and we learn that somebody has kidnapped the heir to the Grendel-Khan. An elite group of soldiers dressed in red body armour is sent off in pursuit on their own hover bikes. They ambush the black clad man and the boy but are killed by him. After they reach Chicago they run into a gang that hates Grendels and think the man is one. He kills them in hand to hand combat and they continue their journey, to New York.

We don’t know why this man has kidnapped the heir or what his goal is or even where they’re going to. Any context we get is from the people responding to the kidnapping, a nameless woman who clearly seems to be some of leader and her assistant Heath. We also meet the woman’s daughter, Crystal, who is kept in the dark as to what happened. But the real context is given in the text box of the front inside cover, that starts with “Chapter 41: Devil in the Desert”, giving us the title of the story and which explains the setting. It’s the 27th century: the late Grendel Khan Orion Assante unified the world. His heir, the boy is Jupiter, who has been cloistered away in that complex we saw, in the Dakota Black Hills, held captive by his stepmother, the reigning regent Laurel Kennedy Assante, the woman trying to get Jupiter back.

But wait a minute. Chapter 41? But isn’t this the first issue of this miniseries?

Well, yes, but this was supposed to come out as the 41st issue of Comico’s Grendel series. Matt Wagner had startedGrendel at Comico as a three issue black and white series: the adventures of gentleman villain Hunter Rose. Wagner reworked this story after the series cancellation in backups to his other big Comico series: Mage but then was done with Grendel, or rather, Hunter Rose’s Grendel. Grendel became a persona that other people could take over and use, or be used by and the second Grendel series explored this, with various new characters picking up the role. Unlike the earlier stories, Wagner would only write, not draw the series, getting new artists for each story arc. By issue forty Grendel has basically taken over the world and Wagner had reached the end of what he wanted to with it. ut then he thought off the story that would become Grendel: Warchild… The idea had been to hand over Grendel entirely to other creators, creating a second series called Grendel Tales, then continue Grendel with issue 41 some months later, but then Comico went bankrupt..

It took two years for everything to clear up and Grendel: Warchild would end up at Dark Horse instead. I’m not sure exactly how much of this issue had been drawn already, but Amazing Heroes Preview Special 11 from Fall 1990 had one McEown page featured in its Batman vs Grendel article. Patrick McEown is an interesting artist. At the time his artwork reminded me of European science fiction artists like Enki Bilal or even Moebius, but now it feels more mangaesque to me? Especially the fight scenes, which are both brutal and funny at times. McEown hasn’t done much else either before or after Grendel: Warchild, having mainly worked on various Aircel series in different roles. A pity, because I like his art.